fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

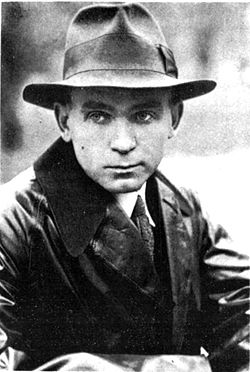

Ulas Oleksiiovych Samchuk (Ukrainian: Улас Олексійович Самчук; 20 February 1905, Derman – 9 July 1987 Toronto) was a Ukrainian writer, propagandist,[1][2][3] publicist, journalist, and a member of the Government of the Ukrainian People's Republic in exile.[4] He was a member of the nationalistic Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, a Nazi Collaborator[5][6][3] and noted antisemite.[7][3]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Ulas Samchuk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 20, 1905 Derman, Volhynian Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | July 9, 1987 (aged 82) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

Biography

Samchuk was born on 20 February 1905, in the village of Derman. From 1917 to 1920 he studied at a four-grade elementary school in Derman. In 1921–1925 he studied at the Kremenets Ukrainian private gymnasium. Before he finished his secondary education, he was called up for service in the Polish Army in 1927, and later deserted in August of that year, escaping to Germany. In Germany he worked delivering coal, and with the help of a supportive German family, Samchuk continued his studies at the University of Breslau.

In 1929, Samchuk moved to Prague, Czechoslovakia. He was attracted by the city's vibrant Ukrainian community and the Ukrainian Free University in which he enrolled, and where he graduated in 1931.

In 1932, while in Prague, Samchuk first heard about the Holodomor famine, and travelled back into Soviet Ukraine to witness the event firsthand. In response, Samchuk wrote the novel Maria (1934)––the first literary work about the famine, and village life at the time.[4] In 1937, on the initiative of Yevhen Konovalets, a cultural office of the Ukrainian nationalist leadership headed by Oleh Olzhych was established. Prague became the centre of the Cultural Office, and one of the main institutions was the Section of artists, writers and journalists, chaired by Samchuk.

In 1941 he returned to Volyn as a member of one of the ultranationalist Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists marching groups, where during 1941–1942, worked for the Nazi's as an editor of the pro-Nazi newspaper Volyn, he notably wrote of the babin yar massacre “Today is a great day for Kyiv”[8][9]

on September 1, 1941, shortly before the Babi Yar massacres Samchuk wrote in Volyn: “The element that settled our cities, whether it is Jews or Poles who were brought here from outside Ukraine, must disappear completely from our cities. The Jewish problem is already in the process of being solved.”[10] Later that month Samchuk added the following: “All elements that reside in our land, whether they are Jews or Poles, must be eradicated. We are at this very moment resolving the Jewish question, and this resolution is part of the plan for the Reich’s total reorganization of Europe.”[7][11]

Fearing repercussions for being a Nazi collaborator he then fled to Nazi Germany in 1944, where he founded and headed the literary-artistic organization MUR until 1948. In 1948, he emigrated to Canada and became the leader of the Slovo Association of Ukrainian Writers in Exile.

He died in Toronto on 9 July 1987.[12] and is buried at the St. Volodymyr Ukrainian Cemetery in Oakville, Ontario.

Work

He published his first short story, "On Old Paths", in 1926 in the Warsaw magazine Nasha Besida. In Samchuk'sVolyn trilogy (I–III, 1932–1937), a collective image of a Ukrainian young man of the late 1920s and early 1930s is derived, which seeks to find Ukraine's place in the world.

From 1929 he began to collaborate regularly with the Literary-Scientific Bulletin, The Bells (magazines published in Lviv), The Independent Thought (Chernivtsi), the Nation-Building (Berlin), and the Antimony (without a permanent location).

Samchuk concurrently wrote the novel Kulak(1932) about the eternal commitment of the Ukrainian peasant to tilling the land and the undying optimism of farmers. His next important work was the two-volume novel The Mountains Speak (1934) which explored Carpatho-Ukraine's struggle against Hungary.[4]

In 1947 he completed the drama Noise of the Mill. The unfinished trilogy Ost: Frost Farm (1948) and Darkness (1957), which depicts the Ukrainian man and his role in the unusual and tragic conditions of interwar and modern sub-Soviet reality.

The topics of Samchuk's final books are about the struggle of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in Volhynia (the novel What Doesn't Heal Fire, 1959) and the life of Ukrainian emigrants in Canada (On Hard Land, 1967). Memoirs of Five to Twelve (1954) and On a White Horse (1956) are devoted to the experience of World War II.[12]

Works

- Volyn (1932–1937)

- Kulak (1932)

- Mountains Are Talking [Hory hovoriat] (1934)

- Maria (1934), (English translation, Maria. A Chronicle of a Life[13] 1952)

- Youth of Vasyl Sheremeta (1946–1947)

- Moroz's Khutir [Moroziv khutir] (1948)

- Darkness [Temnota] (1957)

- Escape from oneself [Vtecha vid sebe]

- People or Servants? [Liudy chy chern]

- Five Past Twelve [Pyat po dvanadtsiatiy] (1954)

- On a White Horse [Na bilomu koni] (1956)

- On a Raven Horse [Na koni voronomu]

- What Fire does not Heal [Choho ne hoit ohon] (1959)

- Where does the river flow? [Kudy teche richka?]

- On Solid Earth [Na tverdiy zemli] (1967)

- In the Footsteps of Pioneers: The Saga of Ukrainian America (1979)

Bibliography

- Ułas Samczuk, Wołyń, wyd. 2 (reprint), ISBN 83-88863-14-2 Biały Dunajec — Ostróg 2005, wyd. «Wołanie z Wołynia»

- Самчук У. Гори говорять. — К., 1996.

- Самчук У. Волинь: У 2 т. — К.: Дніпро, 1993. — Т.1, 2.

- Самчук У. Дермань. Роман: У 2 ч. — Рівне: Волинські обереги, 2005. — 120 с.

- Самчук У. На білому коні. — Львів: Літопис Червоної Калини, 1999.

- Самчук У. На коні вороному. — Львів: Літопис Червоної Калини, 2000.

- Самчук У. Темнота. Роман. — Нью-Йорк, 1957. — 493 с.

- Самчук У. Чого не гоїть огонь. — К.: Укр. письменник, 1994.

- Самчук У. Юність Василя Шеремети: Роман. — Рівне: Волин. обереги, 2005. — 329 с.

- Волинські дороги Уласа Сачука: Збірник. — Рівне: Азалія, 1993.

- Гром'як Р. Розпросторення духовного світу Уласа Самчука (Від трилогії «Волинь» до трилогії «Ost») // Орієнтації. Розмисли. Дискурси. 1997—2007. — Тернопіль: Джура, 2007. — С. 248—267.

- Улас Самчук. Ювілейний збірник. До 90-річчя народження. — Рівне: Азалія, 1994. 274

- Тарнавський О. Улас Самчук — прозаїк // Відоме й позавідоме. — К.: Час, 1999. — С. 336—350.

- Ткачук М. П. Художні виміри творчості Уласа Самчука // Українська мова і література в школі. — 2005. — № 6: — С. 43–47.

References

- Shkandrij, Myroslav (2015). Ukrainian Nationalism. Yale University Press. pp. 242, Chapter 10. ISBN 9780300206289.

- Messina, Adele Valeria (2017). American Sociology and Holocaust Studies: The Alleged Silence and the Creation of the Sociological Delay. Published by Academic Studies Press. pp. 176, 177. ISBN 9781618115478.

- Himka, John-Paul. Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust,. Ibidem Press. p. 102. ISBN 3838215486.

- "Ulas Samchuk Biography". www.languagelanterns.com. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- Shkandrij, Myroslav (2015). Ukrainian Nationalism. Yale University Press. pp. 241, 242, Chapter 10. ISBN 9780300206289.

- Hnatiuk, Ola (2019). Courage and Fear. Academic Studies Press. ISBN 9781644692516.

- Burds, Jeffrey (2013). Holocaust in Rovno (1st ed.). Palgrave McMillan. p. 39. ISBN 9781137388391.

- noah (2021-01-27). "Nazi collaborator monuments around the world". The Forward. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- "Ukrainian communists warn Kiev planning a year of glorifying nazis". Morning Star. 2020-03-03. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- Burds, Jeffrey (2013). Holocaust in Rovno (1st ed.). Palgrave McMillan. p. 8. ISBN 9781137388391.

- Messina, Adele Valeria (2017). American Sociology and Holocaust Studies The Alleged Silence and the Creation of the Sociological Delay. Academic Studies Press. pp. 176, 177. ISBN 9781618115478.

- "Ulas Samchuk". www.myslenedrevo.com.ua. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- Samchuk, U., 1952, “Maria. A Chronicle of a Life, Language Lantern Publications, Toronto, (Engl. transl.)

External links

На других языках

- [en] Ulas Samchuk

[ru] Самчук, Улас Алексеевич

Ула́с Алексе́евич Самчу́к (укр. Самчук Улас Олексійович; 20 февраля 1905 (1905-02-20), с. Дермань, Волынь, Российская империя сейчас Здолбуновский район, Ровненская область, Украина — 9 июля 1987, Торонто, Канада) — украинский прозаик, журналист и публицист, коллаборационист с нацистской Германией. Творчество Самчука было широко известно в украинской диаспоре, однако лишь в конце XX века стало возвращаться на Украину.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии