fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

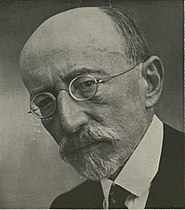

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am (Hebrew: אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zionist thinkers. He is known as the founder of cultural Zionism. With his secular vision of a Jewish "spiritual center" in Israel, he confronted Theodor Herzl. Unlike Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, Ha'am strived for "a Jewish state and not merely a state of Jews".[3]

Ahad Ha'am | |

|---|---|

Ahad Ha'am (Asher Ginsberg) | |

| Born | Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg August 18, 1856 Skvyra, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | January 2, 1927 (aged 70) Tel Aviv, Mandatory Palestine |

| Occupation | essayist, journalist |

| Literary movement | Hovevei Zion |

| Spouse | Rivke (Schneersohn)[1][2] |

Biography

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (Ahad Ha'am) was born in Skvyra, in the Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine) to pious well-to-do Hasidic parents. At eight years old, he began to teach himself to read Russian. His father, Isaiah, sent him to heder until he was 12. When Isaiah became the administrator of a large estate in a village in the Kiev district, he moved the family there and took private tutors for his son, who excelled at his studies. Ginsberg was critical of the dogmatic nature of Orthodox Judaism but remained loyal to his cultural heritage, especially the ethical ideals of Judaism.[4] He married Rivke at the age of 17. They had two children, Shlomo and Rachel. In 1886 he settled in Odessa with his parents, wife and children, and entered the family business.[5] In 1908, following a trip to Palestine, Ginsberg moved to London to manage the office of the Wissotzky Tea company.[6] He settled in Tel Aviv in early 1922, where he served as a member of the Executive Committee of the city council until 1926. Plagued by ill health, Ginsberg died there in 1927.[4]

Zionist activism

In his early thirties, Ginsberg returned to Odessa where he was influenced by Leon Pinsker, a leader of the Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion) movement whose goal was settlement of Jews in Palestine. Unlike Pinsker, Ginsberg did not believe in political Zionism, which he fought, 'with a vehemence and austerity which embittered that whole period'.[7] Instead he hailed the spiritual value of the Hebrew renaissance to counter the debilitating fragmentation (hitpardut) in the diaspora, he believed that the ingathering of Jews in Palestine was not an answer. Kibbutz galuyot was a messianic ideal rather than a feasible contemporary project. The real answer lay in achieving a spiritual centre, or 'central domicile', within Palestine, that of Eretz Israel, which would form an exemplary model for the dispersed world of Jewry in exile to imitate; a spiritual focus for the circumferential world of the Jewish diaspora.[8] He split from the Zionist movement after the First Zionist Congress, because he felt that Theodor Herzl's program was impractical.[9] From 1889 to 1906, Ginzberg flourished as a preeminent intellectual in Zionist politics.

Journalism career

In 1896, Ahad Ha'am founded the Hebrew monthly Ha-Shiloaḥ, the leading Hebrew-language literary journal in the early twentieth century. It was published in Warsaw by Ahiasaf. It was a vehicle to promote Jewish nationalism and a platform for discussion of past and present issues relevant to Judaism. The name was taken from a river mentioned in Isaiah 8:6, “The waters of Shiloaḥ flow slowly,” alluding to the moderate stance of the paper.[10]

Visits to Palestine

Ahad Ha'am travelled frequently to Palestine and published reports about the progress of Jewish settlement there. They were generally glum. They reported on hunger, on Arab dissatisfaction and unrest, on unemployment, and on people leaving Palestine. In an essay[11] soon after his 1891 journey to the area he warned against the 'great error', noticeable among Jewish settlers, of treating the fellahin with contempt, of regarding 'all Arabs a(s) savages of the desert, a people similar to a donkey'.[12][13]

Ahad Ha'am made his first trip to Palestine in 1891. The trip was prompted by concern that the Jaffa members of B'nai Moshe were mishandling land purchases for prospective immigrants and contributing to soaring land prices. His reputation as Zionism's major internal critic has its roots in the essay "A Truth from Eretz Yisrael" published in pamphlet form shortly after his visit in 1891,[14] in which he explained in part:

We who live abroad are accustomed to believe that almost all Eretz Yisrael is now uninhabited desert and whoever wishes can buy land there as he pleases. But this is not true. It is very difficult to find in the land [ha'aretz] cultivated fields that are not used for planting. Only those sand fields or stone mountains that would require the investment of hard labour and great expense to make them good for planting remain uncultivated and that's because the Arabs do not like working too much in the present for a distant future. Therefore, it is very difficult to find good land for cattle. And not only peasants, but also rich landowners, are not selling good land so easily...We who live abroad are accustomed to believing that the Arabs are all wild desert people who, like donkeys, neither see nor understand what is happening around them. But this is a grave mistake. The Arab, like all the Semites, is sharp minded and shrewd. All the townships of Syria and Eretz Yisrael are full of Arab merchants who know how to exploit the masses and keep track of everyone with whom they deal – the same as in Europe. The Arabs, especially the urban elite, see and understand what we are doing and what we wish to do on the land, but they keep quiet and pretend not to notice anything. For now, they do not consider our actions as presenting a future danger to them. … But, if the time comes that our people's life in Eretz Yisrael will develop to a point where we are taking their place, either slightly or significantly, the natives are not going to just step aside so easily. . . .

We must surely learn, from both our past and present history, how careful we must be not to provoke the anger of the native people by doing them wrong, how we should be cautious in our dealings with a foreign people among whom we returned to live, to handle these people with love and respect and, needless to say, with justice and good judgment. And what do our brothers do? Exactly the opposite! They were slaves in their Diasporas, and suddenly they find themselves with unlimited freedom, wild freedom that only a country like Turkey [the Ottoman Empire] can offer. This sudden change has planted despotic tendencies in their hearts, as always happens to former slaves ['eved ki yimlokh – when a slave becomes king – Proverbs 30:22]. They deal with the Arabs with hostility and cruelty, trespass unjustly, beat them shamefully for no sufficient reason, and even boast about their actions. There is no one to stop the flood and put an end to this despicable and dangerous tendency. Our brothers indeed were right when they said that the Arab only respects he who exhibits bravery and courage. But when these people feel that the law is on their rival's side and, even more so, if they are right to think their rival's actions are unjust and oppressive, then, even if they are silent and endlessly reserved, they keep their anger in their hearts. And these people will be revengeful like no other.[15]

Ahad Ha'am believed that Zionism must bring Jews to Palestine gradually, while turning it into a cultural centre. At the same time, it was incumbent upon Zionism to inspire a revival of Jewish national life in the Diaspora. Only then would the Jewish people be strong enough to assume the mantle of building a nation state. He did not believe that the impoverished settlers of his day would ever build a Jewish homeland. He saw the Hovevei Zion movement of which he was a member as a failure because the new villages were dependent on the largesse of outside benefactors.[citation needed]

Importance of Hebrew and Jewish culture

Ahad Ha'am's ideas were popular at a very difficult time for Zionism, beginning after the failures of the first Aliya. His unique contribution was to emphasise the importance of reviving Hebrew and Jewish culture both in Palestine and throughout the Diaspora, something that was recognised only belatedly, when it became part of the Zionist program after 1898. Herzl did not have much use for Hebrew, and many wanted German to be the language of the Jewish state.[16] Ahad Ha'am played an important role in the revival of the Hebrew language and Jewish culture, and in cementing a link between the proposed Jewish state and Hebrew culture.[17]

Cultural Zionism

His first article criticizing practical Zionism, called "Lo zu haderekh" (This is not the way) published in 1888 appeared in HaMelitz.[18] In it, he wrote that the Land of Israel will not be capable of absorbing all of the Jewish Diaspora, not even a majority of them. Ahad Ha'am also argued that establishing a "national home" in Zion will not solve the "Jewish problem"; furthermore, the physical conditions in Eretz Yisrael will discourage Aliyah, and thus Hibbat Zion must educate and strengthen Zionist values among the Jewish people enough that they will want to settle the land despite the greatest difficulties. The ideas in this article became the platform for Bnai Moshe (sons of Moses), a secret society he founded that year. Bnai Moshe, active until 1897, worked to improve Hebrew education, build up a wider audience for Hebrew literature, and assist the Jewish settlements.[19] Perhaps more significant was Derekh Kehayim (1889), Ha'am's attempt to launch a unique movement from a fundamentalist perspective incorporating all the elements of a national revival, but driven by force of intellect.

He eclipsed nationalists like Peretz Smolenskin arguing assimilative individualism in the west further alienated Russified Jewry, who were seeking to reduce migration: isolating it beggared Eastern European Jewry. Even those in Hovevei seeking to restrict emigration would, he feared, bring the extinguishment of national consciousness; and atomisation of Jewish identity. Only anti-Semitism had made Jews of us.[20] Derekh argued that nations had waxed and waned throughout history, but nationalism had all but vanished from Jewish consciousness. Only a small group of nobles kept it going.

Throughout the 1890s Ahad Ha'am worked to keep the flame of nationalism alive.[21] Emphasis fell on moral concepts, honor of the flag, self-improvement, national revitalisation. A departure occurred in Avdut betokh herut[22] discussing pessimism about the future for independent Jewishness. Critic Simon Dubnov alluded to this but was compromised by his westernised idealizing of French Jewry. For the movement, the preoccupation with assimilation at Odessa was fatal for Ha'am's progressive Zionism. The requirement arose in 1891 for a "spiritual centre" in Palestine; Bnei Moshe's implacable opposition to his support for Vladimir (Zeev] Tiomkin's ideal community at Jaffa compounded the controversy in Emet me'eretz Yisrael (The Truth from the Land of Israel).

In 1896, Ginsberg became editor of Hashiloah, a Hebrew monthly, a position he held for six years. After stepping down as editor in 1903, he went back to the business world with the Wissotzky Tea Company.[23]

In 1897, following the Basel Zionist Congress calling for a Jewish national home "recognized in international law" (völkerrechtlich), Ahad Ha'am wrote an article called Jewish State Jewish Problem ridiculing the idea of a völkerrechtlich recognized state, given the pitiful plight of the Jewish settlements in Palestine at the time. He emphasized that without a Jewish nationalist revival abroad, it would be impossible to mobilize genuine support for a Jewish national home. Even if the national home were created and recognized in international law, it would be weak and unsustainable.

In 1898, the Zionist Congress adopted the idea of disseminating Jewish culture in the Diaspora as a tool for furthering the goals of the Zionist movement and bringing about a revival of the Jewish people. Bnai Moshe helped to found Rehovot as a model for self-sufficiency, and established Achiasaf, a Hebrew publishing company.[24]

Political influence

Ahad Ha'am's influence in the political realm can be ascribed to his charismatic personality and spiritual authority rather than his official functions. For the "Democratic Fraction," a party that espoused cultural Zionism (founded in 1901 by Chaim Weizmann), he served "as a symbol for the movement's culturalists, the faction's most coherent totem. He was, however, not – certainly not to the extent to which members of this group, especially Chaim Weizmann, would later contend – its chief ideological influence."[25]

Ahad Ha'am was a talented negotiator. In this role he was engaged during the "language controversy" that accompanied the founding of the Haifa Technikum (today: the Technion) and in the negotiations culminating in the Balfour Declaration.[26]

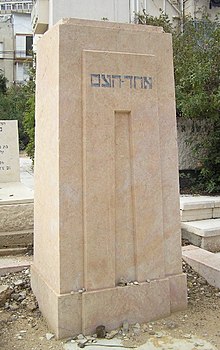

Legacy and commemoration

Many cities in Israel have streets named after Ahad Ha'am. In Petah Tikva there is a high school named after him, Ahad Ha'am High School. There is also a room named after him at the Beit Ariela Library, Ahad Ha'am Room.

Published works

- Ten Essays on Zionism and Judaism, Translated from the Hebrew by Leon Simon, Arno Press, 1973 (reprint of 1922 ed.). ISBN 0-405-05267-7

- Essays, Letters, Memoirs, Translated from the Hebrew and edited by Leon Simon. East and West Library, 1946.

- Selected Essays, Translated from the Hebrew by Leon Simon. The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1912.

- Nationalism and the Jewish Ethic; Basic Writings of Ahad Ha'am, Edited and Introduced by Hans Kohn. Schocken Books, 1962

References

- daughter of shneur zalman mordechai (brother of shterna sarah wife of rabbi sholom dovber the fifth lubavitcher rebbe) son of r. yosef yitzchok of avrutch son of r. menachem mendel the tzemach tzedeck.

- Zipperstein, Steven J. "Ahad Ha-Am". YIVO. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Ha'am, Ahad (1897), translated by Leon Simon, 1912, "The Jewish State and Jewish Problem", Jewish Virtual Library, Jewish Publication Society of America

- Encyclopedia of Zionism and Israel, vol. 1, Ahad Ha'am, New York, 1971, pp. 13–14

- Jews in Eastern Europe: Ahad Ha'am

- David B. Green (8 July 2016). "1824: A Man Whose Name Makes Israelis Think of 'Tea' Is Born". Haaretz. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Shalom Spiegel, Hebrew Reborn,(1939) Meridian Books, Cleveland, New York 1962 p.271

- Shalom Spiegel, Hebrew Reborn, ibid. pp.286–289

- S J Zipperstein, "Ahad Ha'am and the Politics of Assimilation, p.350

- Ha-Shiloah

- 'Truth from Eretz Yisrael',

- Anita Shapira, Land and power: The Zionist resort to force, 1881–1948, Oxford University Press, 1992 p.42

- variant translation in Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate,Metropolitan Books, 2000 p.104

- Kol Kitve Ahad Ha'am, The Jerusalem Publishing House, 1953

- Wrestling with Zion, Grove Press, 2003 PB, p. 14 - 15

- Herzl's German adventure

- "Ahad Ha am (1856 1927)". Archived from the original on 5 January 2009.

- אחד העם Ha'am, Ahad (Asher Zvi Ginzberg), על פרשת דרכים At the Crossroads (Selected Essays) (February 19, 2009) LibriVox recording of at the Crossroads (Selected Essays), by Ahad Ha'am. Read by Omri Lernau (in Hebrew)

- Benei Moshe, Jewish Virtual Library

- Herzl to Nordau; Zipperstein, p.344

- Vital, The People Apart, p.348

- (Slavery in Freedom) published in 1891

- Who's who in Jewish History. David McKay. 2002. p. 15. ISBN 0-415-26030-2.

- Ahad Ha’am (1856 – 1927)

- Steven J. Zipperstein, Elusive Prophet: Ahad Ha'am and the Origins of Zionism, London: Peter Halban 1993, p. 144

- Zipperstein, Elusive Prophet, 269, 296–301

Further reading

- Frankell, J; Zipperstein, J (1992). Assimilation and Community. Cambridge University Press.

- Kipen, Israel (2013). Ahad Ha-am: The Zionism of the Future. Hybrid Publishers. ISBN 9781742982441.

External links

Ahad Ha'am

- Jewish Virtual Library: "Ahad Ha'am" biography

- Jewish Virtual Library: "Ahad Ha'am" short biography

- Jewish Virtual Library: "Anticipations and Survivals”: texts concerning Zionism by Ahad Ha’am (1891).

- “Moses”: Zionist pamphlet by Achad ha-Am (1904), translated into English by Leon Simon. Jewish Miscellanies website.

- Ahad Ha'am (Asher Ginsburg)

- Micha Goodman,Hillel the Elder meets Ahad Ha'am, Eretz Acheret Magazine

- Works by or about Ahad Ha'am at Internet Archive

- Works by Ahad Ha'am at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Newspaper clippings about Ahad Ha'am in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

На других языках

- [en] Ahad Ha'am

[ru] Ахад-ха-Ам

Аха́д ха-А́м (иногда Ахад-Гаам; ивр. אַחַד הָעָם, букв. «один из народа»; настоящее имя — Ушер Исаевич (Ашер Хирш) Гинцберг; 18 августа 1856 (1856-08-18), Сквира, Киевская губерния, Российская империя — 2 января 1927, Тель-Авив, Британский мандат в Палестине) — еврейский писатель-публицист и философ.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии