fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

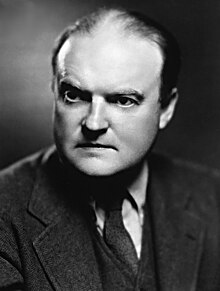

Edmund Wilson Jr. (May 8, 1895 – June 12, 1972) was an American writer and literary critic who explored Freudian and Marxist themes. He influenced many American authors, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose unfinished work he edited for publication. His scheme for a Library of America series of national classic works came to fruition through the efforts of Jason Epstein after Wilson's death.

Edmund Wilson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Edmund Wilson Jr. May 8, 1895 Red Bank, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | June 12, 1972 (aged 77) Talcottville, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | Princeton University |

| Genre | Fiction, review of fiction |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | Mary McCarthy (m. 1938–1946) |

Early life

Wilson was born in Red Bank, New Jersey. His parents were Edmund Wilson Sr., a lawyer who served as New Jersey Attorney General, and Helen Mather (née Kimball). Wilson attended The Hill School, a college preparatory boarding school in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, graduating in 1912. At Hill, Wilson served as the editor-in-chief of the school's literary magazine, The Record. From 1912 to 1916, he was educated at Princeton University, where his friends included F. Scott Fitzgerald and war poet John Allan Wyeth. Wilson began his professional writing career as a reporter for the New York Sun, and served in the army with Base Hospital 36 from Detroit, Michigan, and later as a translator during the First World War. His family's summer home at Talcottville, New York, known as Edmund Wilson House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[1][2][3]

Career

Wilson was the managing editor of Vanity Fair in 1920 and 1921, and later served as associate editor of The New Republic and as a book reviewer for The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books. His works influenced novelists Upton Sinclair, John Dos Passos, Sinclair Lewis, Floyd Dell, and Theodore Dreiser. He served on the Dewey Commission that set out to fairly evaluate the charges that led to the exile of Leon Trotsky. He wrote plays, poems, and novels, but his greatest influence was literary criticism.[4]

Axel's Castle: A Study in the Imaginative Literature of 1870–1930 (1931) was a sweeping survey of Symbolism. It covered Arthur Rimbaud, Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam (author of Axël), W. B. Yeats, Paul Valéry, T. S. Eliot, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein.

In 1932, Wilson pledged his support to the Communist Party USA's candidate for President, William Z. Foster, signing a manifesto in support of CPUSA policies; however, Wilson did not identify personally as a communist.[5] In his book To the Finland Station (1940), Wilson studied the course of European socialism, from the 1824 discovery by Jules Michelet of the ideas of Vico to the 1917 arrival of Vladimir Lenin at the Finland Station of Saint Petersburg to lead the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution.

In an essay on the work of horror writer H. P. Lovecraft, "Tales of the Marvellous and the Ridiculous" (New Yorker, November 1945; later collected in Classics and Commercials), Wilson condemned Lovecraft's tales as "hackwork".[citation needed] Wilson is also well known for his heavy criticism of J. R. R. Tolkien's work The Lord of the Rings, which he referred to as "juvenile trash", saying "Dr. Tolkien has little skill at narrative and no instinct for literary form."[6] He had earlier dismissed the work of W. Somerset Maugham in vehement terms (without, as he later boasted, having troubled to read the novels generally regarded as Maugham's finest, Of Human Bondage, Cakes and Ale and The Razor's Edge).[7]

In 1964, Wilson was awarded The Edward MacDowell Medal by The MacDowell Colony for outstanding contributions to American culture. [8]

Wilson lobbied for the creation of a series of classic U.S. literature similar to France's Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. In 1982, ten years after his death, The Library of America series was launched.[9] Wilson's writing was included in the Library of America in two volumes published in 2007.[10]

Context and relationships

Wilson's critical works helped foster public appreciation for several novelists: Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Vladimir Nabokov. He was instrumental in establishing the modern evaluation of the works of Dickens and Kipling.[11] Wilson was a friend of the novelist and playwright Susan Glaspell as well as the philosopher Isaiah Berlin.[12]

He attended Princeton with Fitzgerald, a year-and-a-half his junior. In 1936 in the "Crack-Up" essays, Fitzgerald referred to Wilson as his "intellectual conscience ... [f]or twenty years".[13] After Fitzgerald's early death (at the age of 44) from a heart attack in December 1940, Wilson edited two books by Fitzgerald (The Last Tycoon and The Crack-Up) for posthumous publication, donating his editorial services to help Fitzgerald's family. Wilson was also a friend of Nabokov, with whom he corresponded extensively and whose writing he introduced to Western audiences. However, their friendship was marred by Wilson's cool reaction to Nabokov's Lolita and irretrievably damaged by Wilson's public criticism of what he considered Nabokov's eccentric translation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin.

Wilson had multiple marriages and affairs.

- His first wife was Mary Blair, who had been in Eugene O'Neill's theatrical company. Their daughter, Rosalind Baker Wilson, was born on September 19, 1923.

- His second wife was Margaret Canby. After her death in a freak accident two years after their marriage, Wilson wrote a long eulogy to her and said later that he felt guilt over having neglected her. Wilson, despondent over Canby's death, moved to a rundown townhouse at 314 East 53rd Street in Manhattan for several years.[14][15]

- From 1938 to 1946, he was married to Mary McCarthy, who like Wilson was well known as a literary critic. She enormously admired Wilson's breadth and depth of intellect, and they collaborated on numerous works. In an article in The New Yorker, Louis Menand wrote, "The marriage to McCarthy was a mistake that neither side wanted to be first to admit. When they fought, he would retreat into his study and lock the door; she would set piles of paper on fire and try to push them under it."[16] This marriage resulted in the birth of their son, Reuel Wilson (born December 25, 1938).[17]

- His fourth wife was Elena Mumm Thornton.[17] Their daughter, Helen Miranda Wilson, was born February 19, 1948.

He wrote many letters to Anaïs Nin, criticizing her for her surrealistic style, because it was opposed to the realism that was then deemed correct writing, and he ended by asking for her hand — "I would love to be married to you, and I would teach you to write" — which she took as an insult.[18] Except for a brief falling-out following the publication of I Thought of Daisy, in which Wilson portrayed Edna St Vincent Millay as Rita Cavanaugh, Wilson and Millay remained friends throughout life. He later married Elena Mumm Thornton (previously married to James Worth Thornton), but continued to have extramarital relationships.

Cold War

Wilson was also an outspoken critic of US Cold War policies. He refused to pay his federal income tax from 1946 to 1955 and was later investigated by the Internal Revenue Service. After a settlement, Wilson received a $25,000 fine, rather than the original $69,000 sought by the IRS. He received no jail time. In his book The Cold War and the Income Tax: A Protest (1963), Wilson argued that as a result of competitive militarization against the Soviet Union, the civil liberties of Americans were being paradoxically infringed under the guise of defense from Communism. For those reasons, Wilson also opposed involvement in the Vietnam War.

Selected by John F. Kennedy to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Wilson, in absentia, was officially awarded the medal on December 6, 1963 by President Lyndon Johnson. However, Wilson's view of Johnson was decidedly negative. Historian Eric F. Goldman writes in his memoir The Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson[19] that when Goldman, on behalf of Johnson, invited Wilson to read from his writings at a White House Festival of the Arts in 1965, "Wilson declined with a brusqueness that I never experienced before or after in the case of an invitation in the name of the President and First Lady."

For the academic year 1964–65, he was a Fellow on the faculty in the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University.[20]

"Edmund Wilson regrets..."

Throughout his career, Wilson often answered fan mail and outside requests for his time with this form postcard:

"Edmund Wilson regrets that it is impossible for him to: Read manuscripts, write books and articles to order, write forewords or introductions, make statements for publicity purposes, do any kind of editorial work, judge literary contests, give interviews, conduct educational courses, deliver lectures, give talks or make speeches, broadcast or appear on television, take part in writers' congresses, answer questionnaires, contribute to or take part in symposiums or 'panels' of any kind, contribute manuscripts for sales, donate copies of his books to libraries, autograph books for strangers, allow his name to be used on letterheads, supply personal information about himself, supply photographs of himself, supply opinions on literary or other subjects".[21]

Bibliography

This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. (February 2022) |

Non-Fiction

- The Undertaker's Garland, (with John Peale Bishop), 1922

- Poets, Farewell!, New York, NY: Charles Scribners's Sons, 1929

- Axel's Castle: A Study in the Imaginative Literature of 1870–1930, New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1931

- The American Jitters: A Year of the Slump, New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1932

- Travels In Two Democracies, New York, NY: Harcourt Brace, 1936

- The Triple Thinkers: Ten Essays on Literature, New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co, 1938

- To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1940

- The Wound and the Bow: Seven Studies in Literature, Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1941

- The Boys in the Back Room, Colt Press, 1941

- The Shock of Recognition: The Development of Literature in the U.S. Recorded by the Men Who Made It (editor), New York, NY: Modern Library, 1943. Illustrations (one-volume edition) by Robert F. Hallock.

- Volume I. The Nineteenth Century

- Volume II. The Twentieth Century

- Europe without Baedeker: Sketches among the Ruins of Italy, Greece and England, 1947 (reissued 1967, as shown below)

- Wilson, Edmund (1948), The Triple Thinkers: Twelve Essays on Literary Subjects, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Co.

- — (1950), Classics and Commercials: A Literary Chronicle of the Forties, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Co.

- — (1952), The Shores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the Twenties and Thirties, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Young.

- Eight Essays, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1954

- The Scrolls from the Dead Sea, Fontana, 1955

- Red, Black, Blond, and Olive: Studies in Four Civilizations: Zuni, Haiti, Soviet Russia, Israel, London: W. H. Allen & Co.; New York: Oxford University Press, 1956

- A Piece of My Mind: Reflections at Sixty, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1956

- The American Earthquake: A Documentary of the Twenties and Thirties (A Documentary of the Jazz Age, the Great Depression, and the New Deal), Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1958

- Apologies to the Iroquois, New York, NY: Vintage, 1960

- Night Thoughts, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, 1961

- Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1962. The title "Patriotic Gore" was taken from the song "Maryland, My Maryland".[22]

- The Cold War and the Income Tax: A protest, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Co., 1964

- O Canada: An American's Notes on Canadian Culture, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Co., 1965

- The Bit Between My Teeth: A Literary Chronicle of 1950–1965, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966

- A Prelude : Landscapes, characters and conversations from the earlier years of my life, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967

- The Fruits of the MLA, New York, NY: New York Review, 1968

- Europe without Baedeker: Sketches among the Ruins of Italy, Greece and England, with Notes from a European Diary: 1963–64: Paris, Rome, Budapest, London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1967

- The Dead Sea Scrolls, 1947–1969, Oxford University Press, 1969, ISBN 0-19500665-8

- Upstate: Records and Recollections of Northern New York, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971

- The Devils and Canon Barham; Ten Essays on Poets, Novelists and Monsters, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973

- The Twenties: From Notebooks and Diaries of the Period, ed. Leon Edel, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975

- Letters on Literature and Politics, ed. Elena Wilson, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977

- The Thirties: From Notebooks and Diaries of the Period, ed. Leon Edel, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980

- The Forties: From Notebooks and Diaries of the Period, ed. Leon Edel, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1983

- The Portable Edmund Wilson, ed. Lewis M. Dabney., New York, NY: Viking Press, 1983

- Wilson, Edmund (1986), Edel, Leon (ed.), The Fifties: From Notebooks and Diaries of the Period, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- — (1993), Dabney, Lewis M (ed.), The Sixties: The Last Journal 1960–1972, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- — (1995), Groth, Janet; Castronovo, David (eds.), From the Uncollected Edmund Wilson, Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

- — (1997), Dabney, Lewis (ed.), The Edmund Wilson Reader, New York, NY: Da Capo Press.

- — (2001), Groth, Janet; Castronovo, David (eds.), Edmund Wilson: The Man in Letters, Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

- — (2001) [1979], Karlinsky, Simon (ed.), Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya: The Nabokov-Wilson Letters, 1940–1971 (revised & expanded ed.), Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- — (2007a), Dabney, Lewis M (ed.), Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s & 30s: The Shores of Light, Axel's Castle, Uncollected Reviews, New York: Library of America, ISBN 978-1-59853-013-1.

- — (2007b), Dabney, Lewis M (ed.), Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1930s & 40s: The Triple Thinkers, The Wound and the Bow, Classics and Commercials, Uncollected Reviews, New York: Library of America, ISBN 978-1-59853-014-8.

Fiction

- "Galahad", 1927 (short story)[23]

- I Thought of Daisy, 1929 (novel)

- Memoirs of Hecate County, Garden City, NY, Doubleday, 1946 (short stories)

Plays

- Cyprian's Prayer 1924

- The Crime in the Whispering Room 1927

- This Room and This Gin and These Sandwiches 1937 (original title "A Winter in Beech Street")

- Beppo and Beth 1937

- The Little Blue Light 1950

- Five Plays 1954 collects Cyprian's Prayer, The Crime in the Whispering Room, This Room and This Gin and These Sandwiches, Beppo and Beth, and The Little Blue Light.

- Dr. McGrath 1967

- The Duke of Palermo 1969

- Osbert's Career, or the Poet's Progress 1969

Book reviews

| Year | Review article | Work(s) reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Wilson, Edmund (January 7, 1950). "Two Russian exiles : Paul Chavchavadze and Oksana Kasenkina". The New Yorker. Vol. 25, no. 46. pp. 74, 77–79. |

|

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009. .

- Wilson, Edmund (biography), Penn State University (PSU), archived from the original on July 20, 2011

- "Wilson, Edmund", Literary map, PSU, archived from the original on July 20, 2011, retrieved February 5, 2011

- Stossel, Scott (November 1, 1996), "The Other Edmund Wilson", The American Prospect, archived from the original on September 17, 2011, retrieved March 22, 2010,

But this has not prevented writers and scholars from trying in recent years to elevate Wilson to what they claim is his rightful status as this century's preeminent American man of letters.

- Menand, Louis (March 17, 2003). "The Historical Romance". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- Wilson, Edmund (April 14, 1956), "Oo, Those awful Orcs!: A review of The Fellowship of the Ring", The Nation, archived from the original on July 6, 2017, retrieved March 15, 2012

- Morgan, Ted (1980). Maugham. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 500–501. ISBN 9780671505813. OCLC 1036531202.

- "Macdowell Medalists". Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- Gray, Paul (May 3, 1982), "Books: A Library in the Hands", Time, archived from the original on January 13, 2005

- McGrath, Charles (October 7, 2007), "A Shaper of the Canon Gets His Place in It", The New York Times, archived from the original on November 28, 2018, retrieved February 22, 2010

- "1, 2", The Wound and the Bow, University Paperbacks, 1941, cat# 2/6786/27

- Berlin, Isaiah (April 12, 1987). "Edmund Wilson Among the 'Despicable English'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (April 1936). "The Crack-Up". Esquire. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- Dabney, Lewis M. (2005). Edmund Wilson: A Life in Literature. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-374-11312-4.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (2003). Edmund Wilson: A Biography. Cooper Square Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4616-6451-2.

- Menand, Louis (August 8, 2005), "Missionary: Edmund Wilson and American Culture", The New Yorker, archived from the original on December 27, 2016, retrieved January 23, 2017

- Alexander Theroux, "On the Cape, vows rewritten: Son of Wilson, McCarthy recounts an unhappy marriage" Archived October 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Boston.com, January 25, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- Nin, Anaïs (1966). The diary of Anaïs Nin. Stuhlmann, Gunther (First ed.). New York. ISBN 0151255938. OCLC 262944.

- Goldman, Eric. "The Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson". Amazon. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- Gillispie, Valerie, ed. (June 2008). "Guide to the Center for Advanced Studies Records, 1958–1969". Wesleyan University. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- "Edmund Wilson Regrets..." Anecdotage.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2014. which cites:

- Whitman, Alden (1981). Come to Judgment. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin Books. p. 199. ISBN 9780140058802. OCLC 7169357.

- Blight, David, "Patriotic Gore is Not Really Much Like Any Other Book by Anyone," Archived June 8, 2022, at the Wayback Machine Slate, March 22, 2012

- Wilson, Edmund, Galahad / I Thought of Daisy, NY, Noonday, 1967; "Foreword", p. viii

Sources

- Presidential Medal of Freedom, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum.

External links

- Ramsey, Richard David (1971), Edmund Wilson: A Bibliography, New York: David Lewis, ISBN 978-0-912012-03-2.

- Wilson, Edmund, Works, Internet Archive.

- Works by Edmund Wilson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Edmund Wilson Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- ———, "Papers and private library", The Department of Special Collections and University Archives, McFarlin Library, The University of Tulsa, archived from the original on November 8, 2010, retrieved October 4, 2010.

- Wilson, Reuel (Winter 2004), "Edmund Wilson's Cape Cod Landscape", Virginia Quarterly Review, archived from the original on October 4, 2006.

- Edmund Wilson at Find a Grave

- Lewis M. Dabney, Edmund Wilson: A Life in Literature, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 0-374-11312-2

На других языках

- [en] Edmund Wilson

[ru] Уилсон, Эдмунд

Эдмунд Уилсон (Вильсон) (англ. Edmund Wilson; 8 мая 1895 года, Рэд-Бэнк, штат Нью-Джерси — 12 июня 1972 года, штат Нью-Йорк) — американский литератор, журналист и критик, один из самых влиятельных литературоведов США середины XX века. Удостоен Президентской медали Свободы (1963).Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии