fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

Jane Wells Webb Loudon (19 August 1807 – 13 July 1858) was an English author and early pioneer of science fiction. She wrote before the term was coined, and was discussed for a century as a writer of Gothic fiction, fantasy or horror. She also created the first popular gardening manuals, as opposed to specialist horticultural works, reframing the art of gardening as fit for young women. She was married to the well-known horticulturalist John Claudius Loudon, and they wrote some books together, as well as her own very successful series.

Jane Wells Webb Loudon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 19 August 1807 Birmingham, United Kingdom |

| Died | 13 July 1858 (aged 50) London, England |

| Occupation | Author |

| Nationality | British |

| Genre |

|

| Literary movement |

|

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse | John Claudius Loudon |

Early life

Jane Webb was born in 1807 to Thomas Webb, a wealthy manufacturer from Edgbaston, Birmingham and his wife. (Sources vary on her place of birth: according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB), she was born at Ritwell House, which is possibly the same as Kitwell House at Bartley Green.) After the death of her mother in 1819, she travelled in Europe for a year with her father, learning several languages. On their return, his business faltered and his fortune was lost to excessive speculation. He sold the house in Edgbaston and moved to another of his properties, Kitwell House at Bartley Green, six miles away. He died penniless in 1824, when Jane Webb was only 17.[1][2][3] Jane Loudon would come to have three major, and dominantly contrasting, intellectual achievements. She was born into a wealthy Birmingham family in 1807, and after the early unfortunate death of her mother in 1819 Jane traveled extensively with her father, businessman Thomas Webb. She explored various cultures and gained familiarity in several languages, which would benefit her later on in her travels. Shortly after Jane began to get her footings again after her mother passed, her father’s business suffered extreme reverses and the family’s fortune rapidly declined. He died shortly after in 1824, leaving Jane an orphan and penniless at 17 years old. At age 20 she would become the first author of a fictional book about mummies, which introduced a new genre seen thriving today. [4] After her marriage to well-known horticulturist and landscape designer, John Loudon, her career shifts into botanical work. Jane would become responsible for introducing gardening to middle-class society by way of her easy to understand gardening manuals. She was a pioneer as a woman to make botanical information accessible to those outside the field, and to further her ideas and her output in society she became a self-taught botanical artist. Through her family, Jane received an excellent education and through the hardship of losing her parents young, she developed the drive to put her capabilities to work. [5]

The Mummy!

When the death of Jane Loudon's parents occurred, she was left to support herself which is why she began her successful writing career. Her first piece of written work was a book full of poetry that was published in 1824. After this work, her focus was shifted towards fictional writings, which is the style of her most known work, "The Mummy". Loudon states, "I had written a strange, wild novel, called the Mummy, in which I had laid the scene in the twenty-second century, and attempted to predict the state of improvement to which this country might possibly arrive."[6]

She may have drawn inspiration from the general fashion for anything Pharaonic, inspired by the French researches during the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt; the 1821 public unwrappings of Egyptian mummies in a theatre near Piccadilly, which she may have attended as a girl, and very likely, the 1818 novel by Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.[2] As Shelley had written of Frankenstein's creation, "A mummy again endued with animation could not be so hideous as that wretch," which may have triggered young Miss Webb's later concept. In any case, at many points she deals in greater clarity with elements from the earlier book: the loathing for the much-desired object, the immediate arrest for crime and attempt to lie one's way out of it, etc.[2] However, unlike the Frankenstein monster, the hideous revived Cheops is not shuffling around dealing out horror and death, but giving canny advice on politics and life to those who befriend him.[2] In some ways The Mummy! may be seen as her reaction to themes in Frankenstein: her mummy specifically says he is allowed life only by divine favour, rather than being indisputably vivified only by mortal science, and so on, as Hopkins' 2003 essay covers in detail.[2]

Unlike many early science fiction works (Shelley's The Last Man, and The Reign of King George VI, 1900–1925, written anonymously in 1763),[7]) Loudon did not portray the future as her own day with mere political changes. She filled her world with foreseeable changes in technology, society, and even fashion. Her court ladies wear trousers and hair ornaments of controlled flame. Surgeons and lawyers may be steam-powered automatons. A kind of Internet is predicted in it. Besides trying to account for the revivification of the mummy in scientific terms – galvanic shock rather than incantations – "she embodied ideas of scientific progress and discovery, that now read like prophecies" to those later down the 1800s.[8] Her social attitudes have resulted in the book being ranked among proto-feminist novels.

The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century was published anonymously in 1827 by Henry Colburn as a three-volume novel, as was usual in that day, so that each small volume could be carried around easily. It drew many favourable reviews, including one in 1829 in The Gardener's Magazine on the inventions it proposed.[n 1][9]

Marriage

Among other foreshadowings of things that were to be, was a steam plough, and this attracted the attention of Mr. John C. Loudon, whose numerous and valuable works on gardening, agriculture, etc., are so well known, led to an acquaintance, which terminated in a matrimonial connection.[8]

John Claudius Loudon wrote a favourable review of The Mummy in a journal he edited. Seeking out the author of the text, whom he presumed to be male, he eventually met Jane in 1830 and they married a year later.[10]

They had a daughter, Agnes Loudon (1832–1863 or 1864), who became an author of children's books. Their circle of friends included Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray.[citation needed]

In 1829, Loudon published the semi-fictional Stories of a Bride, her second and last foray in fiction.

Her husband was considered a leading horticulturalist of the time. She also wrote about the gardening, entry-level works such as the ladies' flower-garden of ornamental annuals.[11]

Jane's Career After Marriage

The Mummy brought Jane into a realm of new possibilities in a way she did not expect, with a career shift into horticulture. John Loudon, popular horniculralist, read the book and gave it a favorable review in his periodical, Gardener's Magazine. He was so impressed and intrigued with the novel he sought out to meet the author in 1830, unknowingly it was Jane. The two were married less than a year later, and he introduced his wife to the field. She commented, “It is scarcely possible to imagine any person more completely ignorant of everything relating to botany than I was at the period of my marriage with Mr Loudon.” [12] She had no previous experience with botany, but Jane was looking for a way to continue her writing career. She immediately stepped up to take on an assistant role to her much older husband. Jane planted and would tend to their extensive gardens, and cared for the plants meticulously in order for John to be able to do his research. With her own writing experience, Jane would assist her husband with editing his publications, in particular his extensive Encyclopedia of Gardening (1834). [13] While Jane worked tentatively with her husband she had realized a major gap in the market, and thus her idea bloomed to create easy to understand gardening manuals. At the time, all articles were written at a level for those already in the field, the manuals were far too technical for the everyday person to understand. With her husband producing these intellectual works it gave her a resource to make gardening understandable and accessible. She traveled with her husband who attended lectures and explored new locations, acting as his literary assistant to record findings or theories, compile the information, and record or edit his articles. Jane worked closely with her husband for the remainder of his career; they believed gardens are a work of art, as well as manifestations of science. [14] Her debout manuals came to fruition in 1840 after the cost of illustrations of her husband’s book put the family into crippling debt. [15]

Loudon’s Botany, Gardening, and Horticulture Works

Along with Jane Loudon's fictional writings, she also created a multitude of gardening books along with botanical artwork. During the time that Jane Loudon lived, men and women were not considered equal, with women being "fit" to carry out tasks such as cooking and cleaning while the men were deemed "fit" to carry out actual jobs. Jane Loudon's eight books of gardening gave women hope and power to be able to complete the task of gardening while getting helpful hints on how to do this effectively from Jane Loudon's works. Her botany, gardening and horticulture books are as follows: "Young ladies book of Botany" created in 1838, "Gardening for Ladies" published in 1840, "The Ladies' Flower Garden of Ornamental Bulbous Plants", "The first book of Botany", and "The Ladies Companion to the Flower Garden" created in 1841, "The Ladies Magazine of Gardening" and "Botany for Ladies" in 1842, and "My Own Garden" in 1855. All of these works taught women how to create beautiful gardens, and also enlightened them by giving them "work" to do in a time where they were not allowed to do such tasks.

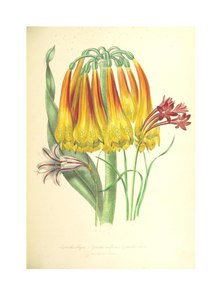

Along with the written works of botany, gardening, and horticulture, Jane Loudon also created many astounding pieces of artwork that depicted the plants from the natural world that she lived in. Her artwork is extremely detailed and has an emphasis on the vibrant colors that some plants in our natural world exhibit. Jane Loudon’s artwork not only is pleasing to the eye, but it creates an understanding in the human population of the importance of plants occurring in our natural world as you can see in the images below. The amazing amount of detail in both "British Wildflowers" and "Verbascums" from “The ladies’ flower-garden of ornamental perennials” not only teaches the viewers what these plants look like, but to also create the natural beauty of nature and all of the plants in It.

Jane as a Botanical Artist

Jane realized early into her new career that illustrations would play a key role in conveying information to the reader. At this time the author decided she needed to teach herself to paint. Jane’s artistic style developed over time and her experience as she became more familiar with the media, as well as her subjects. However the primary consistency in her illustrations includes grouping the flowers into a bouquet form. Her illustrations were popular among women, even seen being used for decoupage on tables, trays, and lampshades. Later on, she began to rely on the new technique of chromolithography which made print production much faster allowing her to increase her output easily. [16]

Later life

John Loudon died of lung cancer in 1843, leaving Jane to raise their 10-year-old daughter Agnes. While earning a living by writing, she received a "deservedly gained" pension of £100 a year from the Civil List.[8]

In late 1849 Loudon began editing The Ladies' Companion at Home and Abroad, a new magazine for women. Successful at first, its sales fell and she resigned. She died in 1858 at the age of 50.[17] After the early death of her husband Jane’s fortunes steadily declined, like she experienced with the death of her father, she was now suffering financial difficulties. In addition to the echoed feeling she experienced with the loss of her father, Jane also had a 12 year old daughter with John who was in need of her care. Around this time she lost her position as editor of The Ladies’ Companion at Home and Abroad magazine, and her book sales began to decline due to competition in sales. Jane would receive an annual pension of £100 from the Civil List, but it was simply not enough to keep Jane and her daughter afloat. She died almost penniless in 1858 at age 51. Her life was relatively short, but in many ways it was spectacular how she explored multiple fields throughout her life. She possessed a rare ability to generate new ideas and cultivate success by carrying information with capacity and creativity. She also had the ability to reinvent herself creatively, she immersed herself in her work with the desire to share to mass audiences. Jane played a massive role in popularizing gardening among women as a new hobby or interest, but unfortunately with the early deaths of both parents, her husband, and the major financial decline from forces outside her control would eventually take their toll.

Legacy

In 2008 a blue plaque was erected in her honour, by Birmingham Civic Society, at Kitwell Primary School, near the site of Kitwell House.[18]

A plaque jointly commemorating Jane and John was erected at their former home, 3 Porchester Terrace, Bayswater in 1953, by London County Council.

Although Jane Loudon's physical legacies are astonishing, they are not the only kind of legacy that is still carried on today by Jane Loudon. The legacy of gardening being a task shifted towards women and children is still widely carried out today, giving power to a population of underrepresented individuals in the world. Jane Loudon was extremely influential to women during her time by giving them power to do something that was not fit for men, and the legacy is still carried on today.

Works

- The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827)[9]

- Stories of a Bride (1829)

- Young Ladies Book of Botany (1838)

- Gardening for Ladies (Second Edition, 1851) (1840)

- The Ladies' Flower-garden of Ornamental Bulbous Plants (1841)

- The first book of botany, 1841 (1841)

- Botany for Ladies (1842)

- The Ladies Magazine of Gardening (1842)

- The Ladies Companion to the Flower Garden (Seventh Edition, 1858) (first edition 1841)

- My Own Garden (1855)

Notes

- Not all critics seem to have read the book carefully. Adams (1865) also says she envisaged a steam-powered plough; Hopkins (2003) says it was a steam-powered milking machine. The on-line copy of The Mummy!: A Tale of the Twenty-second Century, Volume 1 at Google Books refers only to a steam powered digging-machine on page 71. See §Further reading.)

References

- "Profile of Jane Loudon", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxforddnb.com), Retrieved on 5 April 2012.

- Lisa Hopkins, "Jane C. Loudon's The Mummy!: Mary Shelley Meets George Orwell, and They Go in a Balloon to Egypt", in Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text, 10 (June 2003). Cf.ac.uk (25 January 2006). Retrieved on 5 April 2012.

- "Profile of Jane Loudon", Birmingham City Council

- https://www.artinsociety.com/forgotten-women-artists-2-jane-loudon.html

- https://blog.library.si.edu/blog/2018/03/06/not-secret-life-woman-naturalist-mrs-jane-c-loudon-1808-1878/#.Y1awBOzMIbl.

- Shigitatsu Antiquarian Books. Profile of Jane Webb Loudon (1807–1858). Shigitatsu.com. Retrieved on 5 April 2012.

- The reign of George VI. 1900–1925; a forecast written in the year 1763. [London] W. Niccoll, 1763, Published in 1899, Archive.org. Retrieved on 5 April 2012.

- Henry Gardiner Adams (1857). A Cyclopaedia of Female Biography; consisting of Sketches of all Women, who have been distinguished by great Talents, Strength of Character, Piety, Benevolence, or moral Virtue of any kind; forming a complete Record of Womanly Excellence or Ability: Edited by H. G. Adams. Groombridge. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- Mrs. Loudon (Jane) (1828). The mummy!: A tale of the twenty-second century. H. Colburn. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- Marilyn Bailey Ogilvie; Joy Dorothy Harvey (2000). The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: L-Z. Taylor & Francis. p. 806. ISBN 041592040X. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Loudon, Jane (1840). The ladies' flower-garden of ornamental annuals. London: Wiliam Smith. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.142712.

- https://www.parksandgardens.org/people/jane-wells-loudon

- https://www.projectcontinua.org/jane-loudon/

- https://heald.nga.gov/mediawiki/index.php/Jane_Loudon#

- https://www.projectcontinua.org/jane-loudon/

- https://www.artinsociety.com/forgotten-women-artists-2-jane-loudon.html

- Chambers, S. J. (2012). "The Corpse of the Future:Jane C. Loudon's The Mummy! and Victorian Science Fiction". Clarkesworld Magazine. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- "Kitwell". Bartley Green District History Group. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

Sources

- H.G. Adams, Cyclopaedia of Female Biography; consisting of Sketches of All Women who have been distinguished by Great Talents, Strength of Character, Piety, Benevolence, or Moral Virtue of any kind, forming a complete record of Womanly Excellence or Ability; London, 1865.

- Lisa Hopkins, "Jane C. Loudon's The Mummy!: Mary Shelley Meets George Orwell, and They Go in a Balloon to Egypt", Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text 10 (June 2003). Online: Internet (date accessed): http://www.cf.ac.uk/encap/romtext/articles/cc10_n01.html.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Internet Archive, The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827)

- Parks and Gardens. “Jane Wells Loudon.” Parks & Gardens

- “Jane Loudon.” Jane Loudon - History of Early American Landscape Design, Sept. 2021

- Phillip. “Forgotten Women Artists: #2 Jane Loudon.” Journal of ART in SOCIETY, Nov. 2017

- Parilla, Lesley. “(Not so) Secret Life of a Woman Naturalist: Mrs. Jane C. Loudon 1807-1858.” Smithsonian Libraries and Archives / Unbound, 6 Mar. 2018

- Whipp, Koren. “Jane Loudon.” Project Continua

Further reading

- Bea Howe, Lady with Green Fingers: The Life of Jane Loudon (London: Country Life, 1961)

Full text of "The Reign of George VI. 1900–1925; a forecast written in the year 1763". (republished)

External links

| Library resources about Jane Wells Webb Loudon |

- Works by Jane C. Loudon at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jane Wells Webb Loudon at Internet Archive

- Works by Jane Wells Webb Loudon at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Mrs Loudon & the Victorian Garden". Prints & Books. Victoria and Albert Museum. 13 January 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Jane Webb Loudon at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Project Continua: Biography of Jane Loudon Project Continua is a web-based multimedia resource dedicated to the creation and preservation of women’s intellectual history from the earliest surviving evidence into the 21st century.

На других языках

- [en] Jane Wells Webb Loudon

[ru] Лаудон, Джейн

Джейн Лаудон, урождённая Джейн Уэллс Уэбб (англ. Jane C. Loudon; 19 августа 1807, Бирмингем — 13 июля 1858, Лондон) — английская писательница, одна из первых представительниц жанра научной фантастики. Известна также как популяризатор науки для женщин и автор ряда пособий по садоводству.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии