fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

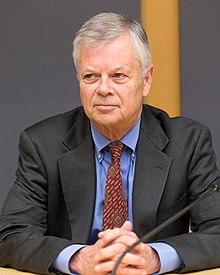

Stephen Kinzer (born August 4, 1951) is an American author, journalist, and academic. A former New York Times correspondent, he has published several books, and writes for several newspapers and news agencies.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Stephen Kinzer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 4, 1951 |

| Alma mater | Boston University (B.A., 1973) |

| Known for | American author, journalist, and academic |

| Website | http://www.stephenkinzer.com |

Reporting career

During the 1980s, Kinzer covered revolutions and social upheaval in Central America, and wrote his first book, Bitter Fruit, about military coups and destabilization in Guatemala during the 1950s. In 1990, The New York Times appointed Kinzer to head its Berlin bureau,[1] from which he covered Eastern and Central Europe as they emerged from Soviet bloc. Kinzer was The New York Times chief in the newly established Istanbul bureau from 1996 to 2000.[1]

Upon returning to the U.S., Kinzer became the newspaper's culture correspondent, based in Chicago, as well as teaching at Northwestern University.[1] He then took up residence in Boston and began teaching journalism and U.S. foreign policy at Boston University. He has written several nonfiction books about Turkey, Central America, Iran, and the U.S. overthrow of foreign governments from the late 19th century to the present, as well as Rwanda's recovery from genocide.

Kinzer also contributes columns to The New York Review of Books,[2] The Guardian,[3] and The Boston Globe.[4] He is a Senior Fellow in International and Public Affairs at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University.[5]

Views

Kinzer's reporting on Central America was criticized by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky in their book Manufacturing Consent (1988), which cited Edgar Chamorro ("selected by the CIA as press spokesman for the contras") in his interview by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting describing Kinzer as "just responding what the White House is saying".[6] In chapter 2 of Manufacturing Consent, Kinzer is criticized for deploying no skepticism in his coverage of the murders of GAM (mutual support group) leaders in Guatemala and for "generally employ[ing] an apologetic framework" for the Guatemalan military state.[6]

Kinzer has since that time criticized what he regards as interventionist U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America and more recently the Middle East.[7] In Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change From Hawaii to Iraq (2006), he critiqued U.S. foreign policy as overly interventionist.[8] In a 2010 interview with Imagineer Magazine, he said:

The effects of U.S. intervention in Latin America have been overwhelmingly negative. They have had the effect of reinforcing brutal and unjust social systems and crushing people who are fighting for what we would actually call "American values." In many cases, if you take Chile, Guatemala, or Honduras for examples, we actually overthrew governments that had principles similar to ours and replaced those democratic, quasi-democratic, or nationalist leaders with people who detest everything the United States stands for.[9]

In his 2008 book A Thousand Hills: Rwanda's Rebirth and the Man who Dreamed It, Kinzer credits President Paul Kagame for what he calls the peace, development, and stability in Rwanda in the years after the Rwandan genocide, and criticizes Rwanda's leaders before the genocide, such as Juvenal Habyarimana.[citation needed] According to Susan M. Thomson, the "book is an exercise in public relations, aimed at further enhancing Kagame's stature in the eyes of the west", is one-sided due to heavy reliance on interviews with Kagame and even apologist.[10]

In a 2016 opinion piece, Kinzer wrote that Aleppo had been liberated from the violent militants who had ruled it for three years by Bashar al-Assad's forces, but that the American public had been told "convoluted nonsense" about the war. He added: "At the recent debate in Milwaukee, Hillary Clinton claimed that United Nations peace efforts in Syria were based on 'an agreement I negotiated in June of 2012 in Geneva.' The precise opposite is true. In 2012 Secretary of State Clinton joined Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Israel in a successful effort to kill Kofi Annan's UN peace plan because it would have accommodated Iran and kept Assad in power, at least temporarily. No one on the Milwaukee stage knew enough to challenge her."[11] Clinton was referencing the Geneva I Conference on Syria, during which principles and guidelines for a power transition were agreed to by the major powers.[12]

In April 2018, he added:

According to the logic behind American strategy in the Middle East—and the rest of the world—one of our principal goals should be to prevent peace or prosperity from breaking out in countries whose governments are unfriendly to us. That outcome in Syria would have results we consider intolerable.[13]

Writings

- Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala, with Stephen Schlesinger; Doubleday, 1982; revised ed. Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-07590-0

- Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001, ISBN 0-374-13143-0

- All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror, John Wiley & Sons, 2003, ISBN 0-471-26517-9

- Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq, Times Books, 2006, ISBN 0-8050-7861-4

- Blood of Brothers: Life and War in Nicaragua, with a new afterword, Harvard University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-674-02593-8

- A Thousand Hills: Rwanda's Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed It, John Wiley & Sons, 2008, ISBN 978-0-470-12015-6

- Reset: Iran, Turkey, and America's Future, Times Books, 2010, ISBN 978-0-8050-9127-4.

- Reset also published as Reset Middle East: Old Friends and New Alliances: Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, Iran, I.B. Tauris, 2010, ISBN 978-1-84885-765-0

- The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War, Times Books, 2013. ISBN 978-0-8050-9497-8.

- The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire, Henry Holt and Co., 2017. ISBN 978-1-6277-9216-5.[14]

- Poisoner in Chief: Sidney Gottlieb and the CIA Search for Mind Control, Henry Holt and Co., 2019, ISBN 978-1-250-14043-2.

See also

- Timeline of United States military operations

References

- "Stephen Kinzer". Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs.

- "Stephen Kinzer". nybooks.com. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- "Stephen Kinzer". theguardian.com. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- "Stephen Kinzer - The Boston Globe". bostonglobe.com. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- "Stephen Kinzer - Watson Institute". brown.edu. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- Chomsky, Noam; Herman, Edweard S. (2002). Manufacturing Consent. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0375714498.

- Interview about the United States and Iran, Democracy Now!, March 3, 2008 (video, audio, and print transcript)

- "Author Kinzer Charts 'Century of Regime Change'". NPR. April 5, 2006.

- "Imagineer :: Stephen Kinzer". December 3, 2009. Archived from the original on December 3, 2009.

- Thomson, Susan M. (2008). "Review of A Thousand Hills: Rwanda's Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed It". International Journal. 64 (1): 304–306. doi:10.1177/002070200906400131. ISSN 0020-7020. JSTOR 40204478. S2CID 146485596.

- The media are misleading the public on Syria, February 18, 2016, The Boston Globe

- "The United Nations in the Heart of Europe - News & Media - Action Group for Syria - Final Communiqué - 30 June 2012". July 10, 2012. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- Kinzer, Stephen. "The US doesn't even care about Syria — but we keep the war going". The Boston Globe.

- Lind, Michael. "Teddy Roosevelt, Mark Twain and the Fight Over American Imperialism". NYT.

External links

- Stephen Kinzer on Twitter

- Official website

- Interview with Kinzer for Guernica Magazine

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "Empirical Evidence", on WNYC's The Brian Lehrer Show, April 26, 2006

- Interview with Stephen Kinzer and Martha Cardenas (mp3) February 10, 2008

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии