fiction.wikisort.org - Movie

Arabian Nights is a 1974 Italian film directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Its original Italian title is Il fiore delle mille e una notte, which means The Flower of the One Thousand and One Nights.

| Arabian Nights | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Pier Paolo Pasolini |

| Written by | Dacia Maraini Pier Paolo Pasolini |

| Based on | One Thousand and One Nights by Various authors |

| Produced by | Alberto Grimaldi |

| Starring | Ninetto Davoli Franco Citti Ines Pellegrini Tessa Bouché Franco Merli Alberto Argentino Jocelyne Munchenbach Margareth Clementi Christian Aligny Salvatore Sapienza Jeanne Gauffin Mathieu Francelise Noel |

| Cinematography | Giuseppe Ruzzolini |

| Edited by | Nino Baragli Tatiana Casini Morigi |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | 20 June 1974 |

Running time | 155 minutes (lost original cut) 125 minutes |

| Countries | Italy France |

| Languages | Italian, Arabic |

The film is an adaptation of the ancient Arabic anthology One Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights. It is the last of Pasolini's "Trilogy of Life", which began with The Decameron and continued with The Canterbury Tales. The lead was played by young Franco Merli who was discovered for this film by Pasolini. The film is an adaptation of several stories within the original collection but they are presented out of order and without the Scheherazade, Dunyazad and King Shahriyar frame story.

The film contains abundant nudity, sex and slapstick humor. It preserves the eroticism and the story within a story structure of Arabian Nights and has been called "perhaps the best and certainly the most intelligent" of Arabian Nights film adaptations.[1]

With this film, Pasolini intended to make a film of Arabian Nights based on his 'memory of it as a boy'. In preparation for the film, Pasolini re-read the 1001 Nights with a more critical lens and chose only the stories that he felt were the most 'beautiful'.[2]

Plot

The main story concerns an innocent young man, Nur-e-Din (Franco Merli), who comes to fall in love with a beautiful slave girl, Zumurrud (Ines Pellegrini), who selected him as her master. After a foolish error of his causes her to be abducted, he travels in search of her. Meanwhile, Zumurrud manages to escape and, disguised as a man, comes to a far-away kingdom where she becomes king. Various other travellers recount their own tragic and romantic experiences, including a young man who becomes enraptured by a mysterious woman on his wedding day, and the prince Shazaman (Alberto Argentino), who wants to free a woman from a demon (Franco Citti) and for whom two women sacrifice their lives. Interwoven are Nur-e-Din's continuing search for Zumurrud and his (mostly erotic) adventures. In the end, he arrives at the far-away kingdom and is reunited with Zumurrud.

The film comprises 16 scenes:[3]

Truth lies not in one dream, but in many dreams. - verse from the 1001 Nights and opening title

- Lady of the Moons: The slave girl Zumurrud is being sold in the marketplace. Her present owner allowed her to choose her new master. Man after man offers to buy her but she refuses. An older man offers to buy her but she laughs and insults his erectile dysfunction. She spots the youth Nur-ed-Din and promises to be his slave. They go back to Nur-ed-Din's home and make love.

- Zumurrud's story: Zumurrud tells her first story-within-the-story about the bisexual poet Sium from Ethiopia of the royal court. (This segment is based on the poetry of Abu Nuwas.) The king spots a woman bathing naked and is sad he has to leave. He asks Sium to compose a poem on the spot about the experience. Afterwards, Sium goes into the town where he propositions three boys for sex. Later, the king and the woman he saw bathing earlier find two youths, a boy and a girl, and drug them with potions. They leave them asleep naked in the same tent on separate cots. They make a bet that whichever of the pair falls in love is the inferior one, as the weaker falls in love with the beautiful. In turn, they wake both the boy and the girl, and both attempt to masturbate on the other's naked body. In the end, Sium and the woman admit there is no clear winner and they leave. Zumurrud is finished with her story and has completed a tapestry. She tells Nur-ed-Din to sell it in the market to anyone except a blue-eyed European man. Nur-ed-Din goes to the market and falls for the blue-eyed man's high offer. The man follows Nur-ed-Din back to his home and asks to share food. He drugs Nur-ed-Din with a banana and steals Zumurrud when he is asleep. The blue-eyed man brings Zumurrud to the old man from the marketplace, and he beats her for having mocked him.

- Nur-e-din's search: Nur-ed-Din is very distressed when he awakens. A female stranger offers to help him. She discovers where Zumurrud is and tells Nur-e-din to wait outside the old man's gate when he is asleep. Zumurrud will jump over the wall and abscond with him. He waits deep into the night but falls asleep. A passing Kurd steals his money and his turban. Zumurrud jumps over the wall and mistakes the Kurd for Nur-ed-Din. The Kurd brings her back to his hideout, where he says his friends will gang rape her. She is chained up but manages to escape the next day and leaves into the desert disguised as a soldier.

- Crowned King: Zumurrud rides through the desert and arrives outside a city guarded by several soldiers and a crowd of people. She claims to be a soldier named Wardan. The people, believing her to be a man, tell her that after the king passes without an heir, their tradition is to crown the first traveller who comes to their city. She is also given a bride. On her wedding night, Zumurrud reveals her secret to the bride. The bride promises to keep her secret. The European man and the Kurd travel to the city and are summarily executed on Wardan's orders. The people they were eating with mistakenly believe this is punishment for stealing a handful of their rice.

- Dream: This segment is based on the story of the Porter and the three ladies of Baghdad from Night 9. Nur-ed-Din is mistaken for a porter by a veiled woman. She hires him to collect various foods and dishes from the market to bring home for her and her two sisters. They return home, set the table and begin reading. In the story-within-the-story, Princess Dunya dreams about a female dove helping her male counterpart fly free from a net. The female is then caught in a net and the male flies off alone. She takes the meaning of this dream as the infidelity of men and vows to never marry.

- Aziz and Aziza: Dunya picks up a book and reads a story. The next story is based on the Aziz and Aziza story that begins on Night 112. Aziz (Ninetto Davoli) is telling his friend, Prince Tagi, about his life. He was set to be married to his cousin Aziza, but on the wedding day, he is distracted by a mysterious woman he meets by chance, when he sits under her window. The woman communicates to him in scant gestures. He is smitten with this woman and goes to Aziza to figure out what to do. Aziza helps decode the messages and tells him how to reply and what poetry to recite. After a rough start, the woman responds to Aziz who looks forward to their meeting in a tent outside the city.

- Love is my Master: Aziz goes to the tent and drinks some wine which puts him to sleep. The woman leaves a sign that she will murder him if he does something so careless again. He goes back and abstains from eating this time. The woman (named Budur) comes and they make love. Aziz recites the poetry Aziza told him to. He returns home and Aziza is on the roof, crushed with loneliness, but Aziz does not seem to care. He only wants Budur. Aziza gives him more poetry to recite. Aziz returns to Budur and after they sleep together, he shoots an arrow with a dildo into her vagina in a highly symbolic scene. Aziz goes home to rest while Aziza cries again. Aziz goes to Budur the next day and recites more poetry but she scolds him. She says the meaning of the poem is that the girl who gave it loved him and has committed suicide. She tells him to go to her grave. He goes and his mother tells him to mourn faithfully but he clearly has little interest in this.

- Weep as you made her weep: Aziz returns to Budur the next day but she is very distraught. She gives him a large sum of money and tells him to erect a monument in Aziza's honor, but he spends all the money on alcohol. After leaving the bar, he is kidnapped by a young woman and her hired thugs. The woman orders him to marry her or Budur, whom he was visiting will kill him. He spends a year with her and fathers a child but he leaves one day on the pretext of visiting his mother. He instead goes to see Budur, who is sitting outside her tent. He asks why she is sitting alone. She responds she has sat alone for one year, not moving an inch, waiting for him. When Aziz tells her he is married and has a child now, Budur tells him he is useless to her now. However, she calls some other women and they surround him with knives. He yells out the last poem Aziza gave him and they are forced to halt. Budur says she won't kill him and that Aziza has saved him this time but that he will not leave unharmed. She ties a rope around his genitalia and castrates him. Aziz returns to his mother who gives him a message from the deceased Aziza. A tapestry he believed was made by Budur was actually made by a woman named Princess Dunya. Prince Tagi hears all this and is moved. He wants to meet Dunya as he has fallen in love with her without even meeting her.

- Garden: The two travel to Dunya's city where she has walled herself off in her palace. They ask the gardener for a tour and he obliges. He says Dunya had a dream about a dove that was betrayed by her male counterpart and has vowed to have nothing to do with men. The two want to meet her under the guise of posing as painters. They plan on hiring two other painters to help them with this disguise. The two are offered seven, eight and even 9 dinars but they refuse to work for anything below one dinar.

- The Painter's story: The men are all painting and working in the palace. Aziz's friend asks the first one what his story is and he replies that he was once a prince who managed to survive a battle by covering himself in a corpse's blood and pretending to be one of the dead. After the enemy leaves, he runs off to a new city to hide. He asks for work and says he knows a lot about philosophy, science, astronomy, medicine and law. The man tells him this is useless to him and the prince will work cutting wood.

- Prince Shahzaman: This is an adaptation of the second dervish's tale from Nights 12 and 13. Prince Shahzaman and his entourage are attacked by robbers. He plays dead and thus survives the attack. Shahzaman goes out to cut wood and accidentally finds a trap door in the ground. He walks down the stairs and finds a beautiful girl trapped underground by a jinn. She tells him that the jinn only comes once every ten days or when she slaps the golden sign above her bed that tells him that she needs him. The prince sleeps with her and he proudly holds his erection in his hand as he announces that he will free her from the jinn. Against her wishes, he hits the golden sign in order to kill the jinn. The prince immediately regrets this and leaves without his shoes before the jinn arrives. The girl tries to explain things to the jinn, that it was only an accident but the jinn realizes she was sleeping with someone when he spies the prince's shoes. He goes out searching for the prince by asking people if they know who the shoes belong to and someone replies yes much to the jinn's happiness. The jinn takes the prince back to the cave and attempts to make the prince kill the girl with a sword but the prince is afraid to do it, having just slept with the girl He also asks the girl to kill the prince but she refuses. Angered and realizing neither will do it, the jinn then chops the girl into pieces himself and takes the prince away to exact his revenge. The jinn tells him that he will not kill him but will transform him into a monkey as punishment for what he has done. The monkey then is picked up by travellers on a ship though it is unknown to them that he was once a man. The travellers are amazed when the monkey takes a paper and brush from them and writes down poetry in beautiful calligraphy. The travellers land at port and go to the king with the paper. The king asks to find whoever wrote such beautiful poetry and throw him a celebration. The people throw a celebration for the monkey. The monkey is adorned with robes and is carried on a litter to the king's surprise. The king's daughter who is knowledgeable of sorcery understands that he was once a man and transforms him back, killing herself in the process. She goes up in flames and only ashes remain of her. Her father, who allowed her to commit suicide, now wants to give the prince a rich gift. But Prince Shahzaman thanks the king for his daughter's self-sacrifice and says he now wants to return to his kingdom.

- Yunan's story: This is an adaptation of the third dervish's story from Nights 14 and 15. In far east Asia, Prince Yunan lives in contentment with his father, the King. Yunan decides to go on a voyage to islands within his kingdom but the ship is blown off course in a storm. He asks the crew why they are crying and they tell him there is an island with a "magnetic mountain" that they are approaching. It will pull all the nails out of their ship and send them to their deaths among the rocks. The ship crashes as they explain but Yunan survives. He hears a voice telling him to grab a bow and arrow buried under the sand and shoot the stone knight statue bearing the cursed talisman that is planted on the peak of the island. He shoots it as he is told and the entire island collapses into the sea. Yunan survives though and drifts among the waves with a piece of wood from his destroyed ship.

- Chamber in the sand: Yunan drifts to another island where he sees a ship disembarking. He runs but it is too late. He finds a chamber on the island and goes inside to find a young boy. The young boy tells him that he is the son of a king and it was foretold by a soothsayer that on that very day he would be killed by a prince named Yunan and so his father took him to the remote island and built a chamber to keep him in until the dangerous time passed. Yunan hears this and tells him he will not hurt him but will only protect him. They bathe together and then go to sleep but during his sleep, Yunan begins sleepwalking and grabs a knife. He stabs the boy with the knife, killing him. (The ending of this story is changed from in the book where the prince accidentally kills the boy while trying to cut a lemon).

- Dream revealed: This segment is based on the porter's story in Night 9. Nur-ed-Din is bathing naked with the three sisters, who are also naked. They are a bit drunk and messing around with each other. One by one, the women ask Nur-ed-Din what their vaginas are called. He answers but they keep telling him he's got the wrong names. The right names are meadowed grass, sweet pomegranates, and the Inn of Good Food. He then asks them what the name of his penis is and each provides an answer though he says they are incorrect. Its name is "the donkey which grazes perfumed meadowed grass, eats peeled sweet pomegranates and spends the night in the Inn of Good Food." He then wakes up the next morning in the terrace outside the women's house. He continues on his search for Zummurrud.

- Nur-e-din and Zumurrud: Nur-ed-Din reaches the city where Zummurrud rules. He grabs a handful of rice from the bowl where people are eating and is taken away to the king's private chamber. Zummurrud (still in disguise) asks him for anal intercourse. He meekly accepts and pulls down his pants. She pulls off her disguise and reveals it was only a joke. They are reunited and they embrace.

Cast

- Ninetto Davoli as Aziz

- Franco Citti as The Demon

- Franco Merli as Nur-Ed-Din

- Tessa Bouché as Aziza

- Ines Pellegrini as Zumurrud

- Alberto Argentino as Prince Shahzaman

- Francesco Paolo Governale as Prince Tagi

- Salvatore Sapienza as Prince Yunan

- Margareth Clementi as Aziz's mother

- Luigina Rocchi as Budur

- Zeudi Biasolo as Zeudi

- Barbara Grandi

- Elisabetta Genovese as Munis

- Gioacchino Castellini

- Jocelyne Munchenbach

- Christian Aligny

- Jeanne Guaffin Mathieu

- Francelise Noel

- Abadit Ghidei as Princess Dunya

- Fessazion Gherentiel as Berhame (Hasan)[4]

Pasolini originally wanted to use more native actors from Iran and other shooting locations in some of the roles but he had to settle for Italian actors and actresses as the Muslim governments did not permit nudity for their citizens.[5] Many of the roles are still played by non-professional native actors, though usually the ones that don't involve nudity. This leads to some odd casting choices such as the Yunan story where Prince Yunan is played by an Italian (Salvatore Sapienza) while his father is clearly played by an East Asian (most likely native Nepalese).

Around this time, Ninetto Davoli who was bisexual and involved with Pier Paolo Pasolini, left him to marry a woman. Pasolini references this by having his story be the one about the man who is instructed on how to woo a woman by a girl who happens to be his fiancé and who dies of a broken heart. Davoli was married in 1973 and this film can be read as Pasolini's farewell to him.[5] This was the first film where Pasolini had Davoli naked with his penis exposed and interestingly, his story in the film ends with him being castrated by his former lover. And it is no coincidence that Aziz is a very insensitive character.

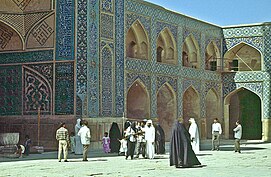

In typical Pasolini fashion, there is also some gender bending casting. Zummurrud's bride is played by the thirteen year son of an Iranian hotel owner who lived near Imam mosque.[6]

Production

Filming took place in Iran, north and south Yemen, the deserts of Eritrea and Ethiopia, and Nepal.[1][7][8] Sium's story that Zummurrud reads about was filmed in Ethiopia with uncredited native actors. Some of the interior scenes were shot at a studio in Cristaldi in Rome.

Locations

Yemen

- Zabid

- Sana'a city walls

- Shibam

- Dar al-Hajar

The market scene at the very beginning of the film was filmed in a town in Yemen named Taiz. The home of Nur-ed-Din, the place where the European man abducts Zummurrud from, is in Zabid.[9] Pasolini had lived there for some time.[10] The desert city that Zummurrud rides to disguised as Wardan was shot at Sana'a. The story of Aziz and Aziza was also filmed here.[9][11]

Princess Dunya's palace is the Dar al-Hajar palace in Yemen.[11] The deleted scenes of Dunya battling her father were filmed in a desert near the location.

The feast of the three sisters and Nur-ed-Din was shot in Shibam.[9][11]

After being attacked in the desert, Prince Shahzmah is being taken into a house in Seiyun.[9]

Iran

- Masjed-e Shah

- Masjed-e Jomeh

- Balcony of Ālī Qāpū

- Music Hall of Ālī Qāpū

- Throne room of Chehel Sotoun

- Room of Chehel Sotoun

At least five monumental buildings of Iran have been used for the film. The Jameh Mosque and the Shah Mosque, both in Esfahan were used as parts of 'King' Zumurud's palace. The Shah Mosque is the place of the wedding feast, where Zummurrud takes revenge on her former captors and where she sees Nur-ed-Din eating at the end of the film. Two real palaces provided parts of the palace as well. The balcony of Ālī Qāpū Palace in Esfahan can be seen as a stage for the wedding celebrations and the throne room of Chehel Sotoun became the King's bedroom. However the entrance to the palace was filmed at the old city walls of Sana'a in Yemen.[9]

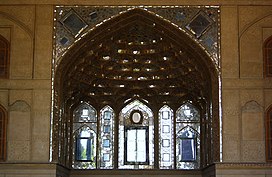

The Music Hall of Ālī Qāpū doubled as the underground chamber where Prince Shahzmah finds a girl who is held prisoner by a demon. Chehel Sotoun provided another underground room. Here Yunan finds a fourteen-year-old boy who is hiding from the man who would kill him on his next birthday.[9]

The Murcheh Khvort Citadel is the place where Nur-ed-Din was hoisted up in a basket by three women.[9]

Shooting was complicated in Isfahan: military guards threw Pasolini and the crew out because they brought donkeys onto the premises of the Shah Mosque and Pasolini had women singing for the scene; this was explicitly prohibited and cost the production a few days delay.[12]

Nepal

- Jaisi Deval Temple

- The Golden Gate in Bhaktapur

- Sundhari Chowk, Patan

- Saraswati Hiti, Patan

- Bhelukhel Square, Bhaktapur

- Kumari Bahal, Kathmandu

The adventures of Yunan begin and end in Nepal. Yunan can be seen playing hide and seek with his friends in and around the Jaisi Deval Temple in Kathmandu[13] and running to his father's palace on Durbar Square in Kathmandu to tell him he wants to go to the sea. He finds his father in the sunken bath of Sundhari Chowk in Patan.[11] After his return home from his adventures he says farewell to his royal life on Bhelukhel Square in Bhaktapur.[14][9]

Prince Shahzmah ends up in Nepal as well. When the King first hears of the monkey sage, he is in the courtyard of Kumari Bahal in Kathmandu. He gives orders to receive the animal with all honours and so a procession is organised to bring him to the palace. The parade passes Saraswati Hiti in Patan, the Ashok Binayak Temple on Durbar Square in Kathmandu, among other places, and ends at the golden gate of Durbar Square in Bhaktapur.[11] In the courtyard of Pujari Math, Dattatreya Square in Bhaktapur, Shahzmah becomes a man again.[9] He too goes off to become a mendicant.

Score

Most of the score was composed by Ennio Morricone and intentionally keeps away from traditional music unlike the first two films of the Trilogy of Life. The music is symphonic. This was to separate it from reality and give it more of a dream-like quality. The Andante of Mozart's String Quartet No.15 is also used in the film. This was to contrast the poverty depicted on the screen with the richness of Mozart's music.[15]

Script

The original script written by Pasolini is very different from what appears in the final film. The set up and flashbacks are much different and more stories from the book are added.[16] In the original script, the film is divided into three parts, the first half, the Intermezzo and the second half. Each part was to have a different frame story which would segue into even more stories in a more conventional framework than the continuous, rhapsodic and fluid form of the final script. In the original prologue of the film, the story opens in Cairo with four boys masturbating to different stories they envision in their heads. These daydreams are based on various stories from the original source material including the erotic poetry of Abu Nuwas, the story of Queen Zobeida and King Harún, the tale of Hasan and Sitt the Beautiful and the stories of Dunya and Tagi and Aziz and Aziza. The stories of the two dervishes were to go in between the last scene. These stories are left out of the final film except for the ones with the Dunya frame narrative. These stories (Dunya and Tagi, Aziz and Aziza, Yunan and Shahziman) are in the final film though much later and in different context.

In the intermezzo, four people of different faiths each believe they have killed a hunchback and tell the Sultan stories to calm his anger. The Christian matchmaker, Muslim chef, Jewish doctor and Chinese tailor each tell their story and avoid the death sentence. The next part was to have Pasolini appearing as himself to the young boys. He kisses each boy, giving them a fragment of the story of Nur-ed-Din and Zummurrud each time. This entire section of the script was left out of the final film.

The most famous shot of the film, where Aziz shoots an arrow laden with a dildo into the vagina of Budur is not in this script. Most of the original script is redone with Nur-ed-Din and Zummurrud as the main narrative and some stories are inserted in different ways to reflect this. The final script does not follow a strict narrative structure but contains a rhapsodic form that moves from story to story.

Dubbing

The same as with The Canterbury Tales which also featured international actors, this movie was shot with silent Arriflex 35 mm cameras and was dubbed into Italian in post-production. Pasolini went to Salento, particularly the towns of Lecce and Calimera to find his voice actors because he believed the local dialect was "pure" and untainted by overuse in Italian comedies and because he saw similarities between Arabic and the Lecce accent.[17][18]

Cinematography

The film was shot with Arriflex cameras. Pasolini refused to adopt one of the most conventional aspects of cinematography at that time, the Master shot. Pasolini never used a Master shot. The scenes are all constructed shot by shot. This guarantees there is no coming back to the story or the characters. It gives the film a free form aspect that anything can happen. The shots still remain perfectly calibrated despite this however. The protagonists are often framed frontally, reminiscent of portraits. He wanted his films to reflect the immediate needs that would be required for his visual storytelling.[5]

Deleted scenes

Pasolini shot a couple scenes that were later discarded from the final film; these can be seen on the Criterion Collection DVD and Blu-ray release.[19] These scenes are silent with no spoken dialogue but with music overlaid. In the first scene, Nur-ed-Din gets drunk at a party and then returns home to hit his angry father. His mother helps him escape to a caravan where he is propositioned for intercourse. In the next scene, Dunya is caught with her lover who is to be executed by her father. She helps him to escape while dressed as a man. Her father follows in pursuit but she fights him off and kills him. Now in a tent while still disguised as a man, Dunya propositions her lover for anal intercourse; he replies timidly by stripping, only for Dunya to pull off her helmet and reveal it was only a joke.[20]

The reason for keeping these scenes out was probably two-fold, the runtime of the film was already too long but also the scenes depict some of the protagonists in a very unflattering light for a film that is intended as an erotic film with light adventure elements. (Nur-ed-Din gets drunk and punches his father and then steals some of his money, and Dunya cuts her father's throat with a knife.) The cross-dressing reveal of the Dunya story was also already used in the film for the story of Zummurrud and Nur-ed-Din.

Themes

Pasolini intended with his Trilogy of Life to portray folksy erotic tales from exotic locales. As with his previous two films, The Decameron (Italy) and The Canterbury Tales (Britain), Arabian Nights is an adaptation of several erotic tales from the near east. Pasolini was much more positive and optimistic with his Trilogy of Life than he was with his earlier films. He was notoriously adversarial and his films often touched on depressing themes. None of that is in this trilogy which stood as a new beginning. Of note is that this is the only film of the trilogy to not be overtly critical of religion. Whereas the previous two were highly critical of the church and clergy, Islam plays very little into this film (though in a deleted scene, Nur-ed-Din's father scolds him for drinking which is prohibited in the Koran). Allah's name is invoked twice in the entire film and none of the characters are seen going to mosque or performing any religious acts of any kind. The characters are very irreligious and the films emphasis on folk superstitions such as ifrits and magic lends emphasis to this.[5] Whereas sexuality is a sin for the characters in the previous two films, no such stigma exists for the characters here.

Open sexuality is a very important topic in this film and this is displayed in the Sium story that Zummurrud tells near the beginning. The poet leaves a naked boy and girl alone to see which of the two is more smitten with the other. Both are taken with one another and there is no clear winner. This shows what follows in the movie, that sexuality is for both genders and all orientations. Desire will be felt equally by both genders and without guilt.

Though earlier translators of the source material (notably Galland) had tried to tone it down, the physical and erotic essence of the stories is quite abundant in these tales. Love in the Nights is not a psychological passion as much as a physical attraction. This is noticeably displayed by Pasolini in his film.[21]

Homosexuality is also depicted in this film in a much more favorable light than in the previous two films. The poet Sium takes three boys to his tent early in the film and in the Muslim society which is very segregated by gender, homoeroticism thrives throughout. The poet Sium can even be seen as a stand-in for Pasolini himself, who frequently searched for young men along the Ostia in Rome. This is in much stark contrast to the previous film The Canterbury Tales, which included an elaborate scene of a homosexual being burned alive at the stake, while the clergy look on smiling.

The film relies much more heavily on flashbacks and stories within stories than the previous two stories. Whereas in the other films, Pasolini himself serves as the one to bind the stories all together (a disciple of Giotto and Geoffrey Chaucer respectively) there is no equivalent character here. Pasolini does not act in this film and the stories are tied together with the Nur-ed-Din frame story and with characters having flashbacks and reading stories to one another. The film's use of flashbacks was likely influenced by Wojciech Has's film The Saragossa Manuscript which at one point, has eight flashbacks-within-flashbacks.[5]

The stories of the two painters both deal with fate and its fickle nature.[22] The first painter's drunken foolishness causes the death of two women, the captive princess and the Asian king's daughter Abriza. This leads him to renounce the world and become a monk. The second painter loses his ship due to his own wish for a sea journey. He is told by the captive child underground that he is the one who will kill him but foolishly believes he can conquer fate and stays with him rather than leave. He ends up killing him in a way he could not anticipate.[23] His story is about attempting to conquer fate. Rather than conquer it he ended up fulfilling it and for this renounced the world and became a painter.

Differences with the source material

The stories are all taken from the 1001 Nights and they stay largely true to the source material, though some of the context is changed and the endings of some stories changed around. The two dervishes who tell their story to the ladies of Baghdad are changed to holy monks who work as painters here. The second dervish's story also ends here with the girl dying as she transforms the dervish back while in the original, she has a battle with the ifrit. This was likely changed to put a quick end to the story and to save time and resources. The third dervish's story is also changed in some parts. He kills the child while sleepwalking here, instead of cutting a fruit. Also his father's ship comes to the island and saves him while in the original he goes to the Palace of the One Eyed Men and the Palace of the Forty Women. The porter's pool joke of Night 9 is also given to Nur-ed-Din. Abu Nuwas's story about hiring three men is also changed to a fictional poet from Ethiopia.

Most notably, the Scheherazade frame story is done away with. Pasolini wanted a different set up for this film without a character framing the tales, as he had already done previously in The Canterbury Tales where he played Chaucer.

Reception

Arabian Nights, and The Trilogy of Life in general, were wildly popular though Pasolini himself turned against the series after their release. In 1975, he wrote an article in the Corriere della Sera lambasting the films. He disliked how the films influenced a series of low quality pornographic films from the same source materials (The Decameron in particular was a rife source for Italian pornographic filmmakers after the success of Pasolini's film) and with what he saw as the commodification of sex. Pasolini responded to his disappointment with the commercial success of these films in his final film Salo.

In June 1974, the director received an obscenity complaint after a preview screening of the film was shown in Milan. Ironically, the funds for the preview were done with the aim of making a documentary in support of the city which would have been beneficial to the local government.[24] The complaint was officially filed on August 5, 1974. The deputy prosecutor of Milan, Caizzi, dismissed it because he acknowledged the film's place as a work of art.

The film offers a polemic against the "neocapitalist petit bourgeois world" which Pasolini claimed to detest. The second level of his polemic was aimed at the leftists who criticized his Trilogy of Life for not "adhering to a specific political agenda right down to the letter." Pasolini felt isolated that so many of his leftist friends and colleagues did not see his Trilogy the way he had intended it to be seen. He felt they were overly critical of his films and missed the point of them.[25]

Awards

The film was entered into the 1974 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Grand Prix Spécial Prize.[26]

See also

- A Thousand and One Nights (1969 film)

- List of works influenced by One Thousand and One Nights

- Orientalism

References

- Irwin, Robert (2004). "The Arabian Nights in Film Adaptations". In Marzolph, Ulrich; Leeuwen, Richard van; Wassouf, Hassan (eds.). The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 24. ISBN 9781576072042.

- 27th international cannes film festival, Pasolini remarks

- Arabian Nights DVD booklet BFI 2009

- Greene, Sheleen (2014). Equivocal Subjects: Between Italy and Africa - Constructions of Racial and National Identity in the Italian Cinema. Bloomsbury.

- "On Arabian Nights", visual essay by Tony Rayns

- Gideon Bachmann, 1973 winter edition Film Quarterly

- Film credits of the DVD edition

- Arabian Nights (1974), archived from the original at TCM.com, retrieved 24 December 2020

- Film Locations, IMDb.com, retrieved 4 January 2021

- Il Medio Oriente di Pasolini, Q Code Magazine, 24 June 2014, retrieved 4 January 2021

- Il Fiore Delle Mille E Una Notte (1974) film locations, Movie-locations.com, retrieved 26 June 2019

- Gideon Bachmann, Winter 1973 edition Film Quarterly

- Jaisidewal, Nhu Gha, Facebook.com, retrieved 26 June 2019

- Arabian Movie Shooting in Bhelukhel, Bhaktapur in 1974, YouTube, 14 March 2018, retrieved 24 December 2020

- Ennio Morricone interview

- Gianni Canova, Trilogia della vita: Le sceneggiature originali de "Il Decameron", "I racconti di Canterbury", "Il Fiore di Mille e una notte, Grazanti

- "2005. Omaggi a PPP trent'anni dopo. Parte seconda". Centrostudipierpaolopasolinicasarsa.it. 20 December 2015.

- (Mauro Marino, La Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno, 2 November 2005).

- "Arabian Nights". Criterion.com.

- Deleted Scenes from the film Arabian Nights, YouTube, retrieved 24 December 2020

- Jack Zipes (ed.). "The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales" (PDF). Cloudflare-ipfs.com. Retrieved 2022-01-24.

- "The Arabian Nights The Second Dervishs Tale Summary". Coursehero.com.

- "The Arabian Nights The Third Dervishs Tale Summary". Coursehero.com.

- "Tesi Luigi Pingitore Sesto". Archived from the original on 2012-10-05.

- 27th international cannes film festival, Pasolini's remarks

- "Festival de Cannes: Arabian Nights". Festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

External links

- Arabian Nights at IMDb

- Arabian Nights at Rotten Tomatoes

- Arabian Nights at AllMovie

- "Pasolini's Splendid Infidelities: Un/Faithful Film Versions of The Thousand and One Nights" by Michael James Lundell. Adaptation: The Journal of Literature On Screen Studies (2012).

- Arabian Nights: Brave Old World an essay by Colin MacCabe at the Criterion Collection

На других языках

- [en] Arabian Nights (1974 film)

[ru] Цветок тысячи и одной ночи

«Цветок тысячи и одной ночи» (итал. Il Fiore Delle Mille E Una Notte) — фильм Пьера Паоло Пазолини 1974 года по мотивам сказок арабской и персидской литературы. Третья часть так называемой «Трилогии жизни[it]», в которую, кроме того, входят «Декамерон» (1971) и «Кентерберийские рассказы» (1972).Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии