fiction.wikisort.org - Movie

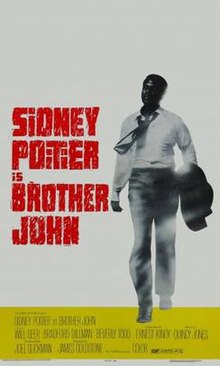

Brother John is a 1971 American drama film about an enigmatic African-American man who shows up every time a relative is about to die.[1] When he returns to his Hackley, Alabama hometown as his sister is dying of cancer, it incites the suspicion of notable town officials.

| Brother John | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | James Goldstone |

| Written by | Ernest Kinoy |

| Produced by | Joel Glickman |

| Starring | Sidney Poitier |

| Cinematography | Gerald Perry Finnerman |

| Edited by | Edward A. Biery |

| Music by | Quincy Jones |

Production company | E&R |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

John Kane's arrival in town coincides with unrest at a factory where workers are seeking to unionize. Local authorities wrongly suspect John to be an outside organizer for the union cause. The suspicions of the local Sheriff and Doc Thomas' son, the District Attorney, grow after they search John's room and find a passport filled with visa stamps from countries all over the world, including some that few Americans are allowed to travel to. They also find newspaper clippings in a variety of different languages. They consider that he might be a journalist or a government agent. Only Doc Thomas, who was the Kane family's physician for many years, suspects that John is none of those things.

After the funeral of John's sister, he admits to a young woman, Louisa, a teacher at the local elementary school, that his "work" is finished, and that he has a few days to "do nothing" before he must leave. She initiates a relationship with him, hoping that he will stay. This puts him at odds with a local man who has had his eyes on her since they were in high school.

During a conversation with Louisa in which he says he will not be returning to Hackley again, John mentions that one of his school friends, now a union organizer, will die soon. When that happens, word of his prediction finds its way to the Sheriff, who uses it as an excuse to arrest John.

During his subsequent questioning John tells them about some of his travels, but he never says exactly what his "work" is. Doc Thomas comes to visit him in jail, and they have a revealing though still somewhat couched conversation, which includes John telling Doc of all the horrors he has witnessed. John then walks out of jail and leaves town while the Sheriff and his men are preoccupied with the local labor unrest.

Throughout the film there are allusions to John's true nature in a confrontation with the sheriff, his hesitant relationship with Louisa, his unexplained ability to travel extensively, his apparent facility with multiple languages, and his apparent aloofness.

Towards the end of the film, the conversation that John has with Doc Thomas appears to imply that the "End of Days" (as mentioned in the Book of Revelation) is close at hand. This is reinforced when Doc asks if it will come by fire and emphasized by the fact that John may be more than he appears to be when he opens without difficulty an apparently locked jail cell door.

Cast

- Sidney Poitier as John Kane

- Will Geer as "Doc" Thomas

- Bradford Dillman as Lloyd Thomas

- Beverly Todd as Louisa MacGill

- Ramon Bieri as Orly Ball

- Warren J. Kemmerling as George

- Lincoln Kilpatrick as Charley Gray

- P. Jay Sidney as Reverend MacGill

- Richard Ward as Frank

- Paul Winfield as Henry Birkart

- Zara Cully as Miss Nettie

- Michael Bell as Cleve

- Howard Rice as Jimmy

- Darlene Rice as Marsha

- Harry Davis as "Turnkey"

- Lynn Hamilton as Sarah

Critical reception

The film was negatively reviewed by Vincent Canby in The New York Times, who stated, "If Brother John is a disaster—and it is—the responsibility is Mr. Poitier's, whose company produced the movie and hired everyone connected with it. Time has run out. It's too late to believe that he's still a passive participant in his own, premature deification."[1] Tom Hutchinson gave the film a two-star review in Radio Times, concluding that "[a]s a fantasy it's pleasant enough, but James Goldstone's film could have been [sic] much more searching in its implications."[2]

By contrast, actors Forest Whitaker, Charles S. Dutton and comedian Reginald D Hunter speak positively about the story elements of Brother John and how Poitier's performance affected them[3] and Dutton stated he thinks it is Poitier's best performance.

In a 2019 essay ("Brother John: Reclaiming the Blackest Movie Ever"), author Scott Woods explains it thusly:

"Every year it’s the same thing: the stepchild that is February tromps down the stairs, announces that it wants to be called by its non-government name for the next 28 days, and Black History Month begins anew. It is a time when black institutions are to be celebrated… Of them all, we hold our cinematic ones extremely high: The Color Purple, Malcolm X, Coming to America, Roots…the list is long, but earned. We take this canon very seriously.. And yet every year, to my constant and recurring dismay, no one ever talks about the blackest film ever: Sidney Poitier’s mystery/drama Brother John. In 1971 Sidney Poitier opted to produce and star in Brother John at the height of not only his acting powers, but the height of his popularity, which even at the end of the civil rights era, were profound. Poitier was not the first black person to receive an Oscar (shout out to Hattie McDaniel), but he was the first black person to win a Best Actor Oscar.. during a time when America was deep in the throes of legalized racism… Three years after Brother John came out Poitier would become one of the few black people to be knighted, and not one of the honorary ones, so that’s Sir Sidney Poitier, if you please. Given the freedom to make any film, he decided to do Brother John, and his intention shows in every frame in which he is present. "Poitier plays John Kane – the titular “Brother John” – a mysterious figure who shows up in his small and barely desegregated Alabama hometown whenever someone in his family dies, an angel of death who comes and goes with a whisper and no information about where he’s been or what he’s been doing. No one calls him, no one sends him word…he just shows up, then leaves. The stage for the film is set when his sister Sarah dies and, once again, he shows up at her deathbed (“I was just passing through”)… The fact that he keeps a journal written in many languages, has no clear source of income, and has a passport to not only dozens of countries, but places virtually impossible for an American to access at the end of the 1960s (let alone a black man), only makes him more suspicious. Only the old town doctor suspects that there is more to Brother John, that in all his comings and goings he has come one final time to not only oversee the passing of another family member, but to herald the end of the world. Doc Thomas believes that Brother John may literally be an angel of death, come to weigh man’s sins like a suit-wearing Anubis on Judgement Day.. "Poitier’s infamous slap scene from In the Heat of the Night is followed up here by a full-blown ass-whuppin’ of a racist sheriff. Later, he presages what would become a blaxploitation staple as he singlehandedly dismantles a gang of drunk homies while protecting his woman. All of this he does without taking off his tie or with an ounce of trash talking. Released one month before Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song, three months before Shaft, and a year before Superfly, Poitier’s John taps into the same thirst for masculine hero archetypes as its blaxploitation brethren, but without the politically nullifying baggage.

"Brother John… kept white critics in harrumphing coughing fits and black audiences pining for more escapist fare. In 1971 black people were fresh off several assassinations of people who stood firm in their interests and were starting to resign themselves to the reality that desegregation without enforceability was still segregation. Brother John did not beat what audiences it was able to muster over the head with its wisdom, but it was too much for people to transpose themselves into. Poitier perhaps did his job too well. Poitier wanted to do Brother John but America needed him to do Brother John. And then no one went to see it. "Brother John has it all, and does all things well: civil rights, racism, classism, toxic masculinity, black love, house parties, homecooked funeral rites. You haven’t celebrated Black History Month properly until you’ve seen this film. Brother John is a perfect black film, both for its time and now, generating even more resonance as we walk every day in a world aflame with hate and neglect."

See also

- List of American films of 1971

References

- Canby, Vincent (March 25, 1971). "Brother John (1970) Stern Angel Returns Home to Hackley, Ala". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2016-03-07.

- Hutchinson, Tom. "Brother John (1970)". RadioTimes.com. Radio Times.

- "The Legacy of Sidney Poitier" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6EWBrhNR1iA

External links

- Brother John at IMDb

- Brother John at the TCM Movie Database

- Brother John at AllMovie

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии