fiction.wikisort.org - Movie

Men Behind the Sun (Chinese: 黑太陽731, literally Black Sun: 731, also sometimes called Man Behind the Sun) is a 1988 Hong Kong historical exploitation horror film directed by T. F. Mou, and written by Mei Liu, Wen Yuan Mou and Dun Jing Teng. The film is a graphic depiction of the war atrocities committed by the Japanese at Unit 731, the secret biological weapons experimentation unit of the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. It details the various cruel medical experiments Unit 731 inflicted upon Chinese and Siberian prisoners towards the end of the war.

| Men Behind the Sun | |

|---|---|

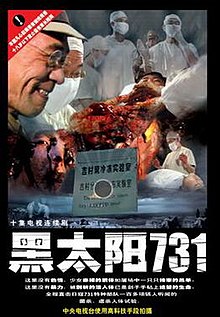

Theatrical release poster | |

| Traditional | 黑太陽731 |

| Simplified | 黑太阳731 |

| Mandarin | hēi tàiyáng 731 |

| Literally | Black Sun 731 |

| Directed by | T. F. Mou |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

Production company | Sil-Metropole Organisation |

| Distributed by | Grand Essex Enterprises |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | Hong Kong |

| Language | Mandarin Chinese |

| Box office |

|

It is the first film to be classified "level III" (equivalent to the US rating NC-17) in Hong Kong.

Plot

The film opens with the passage "Friendship is friendship; history is history."

A group of Japanese boys are conscripted into the Youth Corps. They are assigned to the Kwantung Army, and are brought to one of the facilities serving Unit 731, which is headed by Shiro Ishii. Soon, they are introduced to the experiments going on at the facility, for which they feel revulsion. The purpose of the experiments is to find a highly contagious strain of bubonic plague, to be used as a last-ditch weapon against the Chinese population.

Meanwhile, the young soldiers befriend a local mute Chinese boy with whom they play games of catch. One day, the commanding officers ask the boys to bring the Chinese child to the facility. Naively, they follow orders believing that no real harm will come to the boy; however, the senior medical staff places the boy in surgery for the purpose of harvesting his organs for research. When the young soldiers realize what has happened, they stage a minor uprising by ganging up and physically beating their commanding officer.

As the war goes on, the situation becomes increasingly desperate for the Japanese, and therefore Unit 731. In one of their last experiments, they tie a number of Chinese prisoners to crosses, intending them to be used as targets for a prototype ceramic bomb containing infectious fleas; however, they are not able to contact their airfield due to a retreat. Chinese prisoners break free from the crosses, and attempt to escape; however, Japanese troops hunt them down, and nearly all of them are run over or shot, including several Japanese.

Returning to the facility after the aborted experiment, Unit 731 runs out of time and they are forced to destroy their research and all other evidence of the atrocities happening there. Dr. Ishii initially orders his subordinates and their families to commit suicide, but is persuaded instead to evacuate them and only commit suicide if captured. However, he makes it clear that secrecy is to be maintained, with dire consequences.

Japanese troops gather at a train station to be transported out of China. One of the Chinese prisoners, having disguised himself and escaped with a group of soldiers, is discovered by an officer. During a short scuffle in which he kills the officer before being killed himself, his blood stains the Japanese flag, to the horror of the Youth Corps. The train leaves the station.

The closing passages reveal that Dr. Ishii cooperates with the Americans, giving them his research and agreeing to work for them. Years later, he is moved to the Korean front, and biological weapons appear on the battlefield shortly thereafter. The Youth Corps involved with 731 are revealed to have led hard lives after the war, but kept the vow that none of the atrocities they witnessed would be revealed or discussed to the public.

Cast

- Gang Wang as Lt. Gen. Shirō Ishii

- Hsu Gou

- Tie Long Jin

- Zhao Hua Mei

- Zhe Quan

- Run Sheng Wang

- Dai Wao Yu

- Andrew Yu

Controversy

Though Mou claims he was trying to depict historical accuracy with the film,[1][2] he has been criticized by Hong Kong critics that the film's appearance as an exploitation film negates any educational value involving a historical atrocity, and Japanese critics deamed the film as anti-japan propaganda.[3]

Because of its graphic content, the film has suffered mass controversy with censors all over the world. It was originally banned in Australia[4] and caused public outcry in Japan to such an extent that director Mou even received threats on his life.[5][2] The film was given several minutes of mandated cuts to be allowed a release in the United Kingdom.[6]

The film garnered further controversy for its use of what Mou claims to be actual autopsy footage of a young boy and also for a scene in which a live cat appears to be thrown into a room to be eaten alive by hundreds of frenzied rats.[7] Although in the 2010 documentary Black Sunshine: Conversations With T.F. Mou, Mou confessed that the cat was tired after participation in the film and got two fish as a reward, that the cat was made wet with honey and theater blood (as opposed to real blood like other scenes as the rat would attack otherwise), and that the rats were licking and eating the honey only.

Reception

The film was panned for its directionless narrative & insensitivity to historical tragedies. From contemporary reviews, "Lor." of Variety declared the film to be a "lowbrow exploitationer treating a serious subject, Japanese war atrocities." noting that "Explosive material is dramatically potent and could have been handled tastefully, as with Kon Ichikawa's classic films like Fires on the Plain" but "resorts to nauseating sensationalism, with butcher-shop depiction of autopsies on live subjects, a disgusting "decompression" experiment spewing intestines out of a victim and a horrendously realistic scene of a pussycat bloodily mauled by a room full of rats."[8]

Sequels

The film spawned three pseudo-sequels:

- Unit 731: Laboratory of the Devil (黑太陽731續集之殺人工廠, 1992)

- Narrow Escape (死亡列車, 1994)

- Black Sun: The Nanking Massacre (黑太陽─南京大屠殺, 1995)

See also

- Philosophy of a Knife

- Unit 731

References

- "Interview-Tun Fei Mous". HorrorView.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- Donato Totaro. "T.F. Mous - The Man Behind the Sun". Horschamp.qc.ca. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- "Foreign Objects: Philosophy of a Knife". Film School Rejects. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Man Behind the Sun 1 & 2". Refused-Classification.com. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- Hicks, Jess (20 December 2016). "The Awful Truth Of MEN BEHIND THE SUN". Birth.Movies.Death. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "Man Behind the Sun (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 22 August 1988. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Hawker, Philippa (23 April 2004). "The Man Behind the Sun". The Age. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- Lor. 1991.

Sources

- Lor. (1991). Variety's Film Reviews 1989-1990. Vol. 21. R. R. Bowker. There are no page numbers in this book. This entry is found under the header "April 5, 1989". ISBN 0-8352-3089-9.

External links

- Men Behind the Sun at IMDb

- Men Behind the Sun at Rotten Tomatoes

- Robert Firsching's review

На других языках

- [en] Men Behind the Sun

[ru] Человек за солнцем

«Человек за солнцем» или «Отряд 731» (кит. трад. 黑太陽731, упр. 黑太阳731, пиньинь hēi tàiyáng 731, буквально: «Чёрное солнце 731») — гонконгский фильм, повествующий о бесчеловечной деятельности Отряда 731 — японской секретной лаборатории по производству биологического оружия, находившейся на территории Маньчжурии в районе Харбина во время Второй мировой войны.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии