fiction.wikisort.org - Movie

Scott of the Antarctic is a 1948 British adventure film starring John Mills as Robert Falcon Scott in his ill-fated attempt to reach the South Pole. The film more or less faithfully recreates the events that befell the Terra Nova Expedition in 1912.

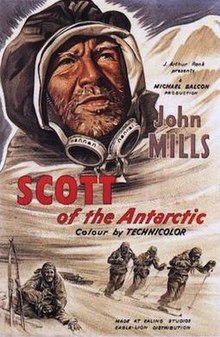

| Scott of the Antarctic | |

|---|---|

Original cinema poster | |

| Directed by | Charles Frend |

| Written by | Walter Meade Ivor Montagu Mary Hayley Bell |

| Produced by | Michael Balcon |

| Starring | John Mills James Robertson Justice Barry Letts |

| Cinematography | Osmond Borradaile Jack Cardiff Geoffrey Unsworth |

| Edited by | Peter Tanner |

| Music by | Ralph Vaughan Williams (as Vaughan Williams) |

| Color process | Technicolor |

Production company | Ealing Studios |

| Distributed by | General Film Distributors (UK) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £3.37 million |

The film was directed by Charles Frend from screenplay by Ivor Montagu and Walter Meade with "additional dialogue" by the novelist Mary Hayley Bell (Mills' wife). The film score was by Ralph Vaughan Williams, who reworked elements of it into his 1952 Sinfonia antartica. The supporting cast included James Robertson Justice, Derek Bond, Kenneth More, John Gregson, Barry Letts and Christopher Lee.

Much of the film was shot in Technicolor at Ealing Studios in London. Landscape and glacier exteriors from the Swiss Alps, Norway, and pre-war stock footage of Graham Land were used but no actual scenes were done in Antarctica.

Plot

Captain Scott is given the men, but not the funds, to go on a second expedition to the Antarctic. As his wife works on a bust of him, she tells him that she's "not the least jealous" that he's going to the Antarctic again. The wife of Dr. E. A. Wilson, whom Scott hopes to recruit, is much less enthusiastic, but Wilson agrees to go on condition it is a scientific expedition. Scott also visits Fridtjof Nansen, who insists that a polar expedition must use only dogs, not machines or horses. Scott goes on a fundraising campaign, with mixed results, finding scepticism among Liverpool businessmen, but enthusiasm among schoolchildren who fund the sledge dogs. With the help of a government grant he finally manages to raise enough money to finance the expedition.

After a stop in New Zealand, the ship sets sail for Antarctica. They set up a camp at the coast, where they spend the winter and hold a MidWinter Feast on 22 June 1911. In the spring a small contingent of men, ponies and dogs begins the trek towards the pole. About halfway, the ponies are, as planned, shot for food and some of the men are sent back with the dogs. At the three quarter mark, Scott selects the five-man team to make the push to the pole, hoping to return by the end of March 1912. They reach the pole only to find the Norwegian flag already planted there and a letter from Roald Amundsen asking Scott to deliver it to the King of Norway.

Hugely disappointed, Scott's team begins the long journey back. When reaching the mountains bordering the polar plateau, Wilson shows the men some sea plant and tree fossils he has found, also a piece of coal, to Scott's satisfaction, proving that the Antarctic must have been a warm place once, and opening economic possibilities. The perceived lack of such opportunities had been one criticism leveled at Scott while fundraising. Nevertheless, Scott is increasingly concerned about the health of two men: Evans, who fell and has a serious cut on his hand, and Oates, whose foot is appallingly frostbitten. Evans eventually collapses and dies, and is buried under the snow. Realising that his condition is slowing the team down, Oates says "I hope I don't wake tomorrow" but when he does, he sacrifices himself crawling out of the tent, saying "I'm just going outside; I may be away some time."[1] (sic`; the words as famously recorded by Scott are "...and may be some time"] Finally, just 11 miles short of a supply depot, the rest of the team dies in their tent trapped by a blizzard. Each man writes his farewell letters, with frostbitten Scott recalling his wife and writing the famous Message to the Public "I do not regret this journey…"

Months later, on a clear sunny day, the search party discovers the completely snowed-over tent. After a shot of Scott's diary being recovered, the film ends with the sight of a wooden cross with the five names of the dead inscribed on it as well as the quote: "To strive to seek to find and not to yield." (Commas left out; a line from the poem "Ulysses", by Alfred, Lord Tennyson.)

Cast

- John Mills as Captain R.F. Scott R.N.

- Diana Churchill as Kathleen Scott

- Harold Warrender as Dr. E.A. Wilson

- Anne Firth as Oriana Wilson

- Derek Bond as Captain L.E.G. Oates

- Reginald Beckwith as Lieutenant H.R. Bowers

- James Robertson Justice as Petty Officer 'Taff' Evans R.N.

- Kenneth More as Lieutenant E.G.R. 'Teddy' Evans R.N.

- Norman Williams as Chief Stoker W. Lashly R.N.

- John Gregson as Petty Officer T. Crean R.N.

- James McKechnie as Surgeon Lieutenant E.L. Atkinson R.N.

- Barry Letts as Apsley Cherry-Garrard

- Dennis Vance as Charles S. Wright

- Larry Burns as Petty Officer P. Keohane R.N.

- Edward Lisak as Dimitri

- Melville Crawford as Cecil Meares

- Christopher Lee as Bernard Day

- John Owers as F.J. Hooper

- Bruce Seton as Lieutenant H. Pennell R.N.

- Clive Morton as Herbert Ponting

- Sam Kydd as Leading Stoker E. McKenzie R.N.

- Mary Merret as Helen Field

- Percy Walsh as Chairman of Meeting

- Noel Howlett as First Questioner

- Philip Stainton as Second Questioner

- Desmond Roberts as Admiralty Official

- Dandy Nichols as Caroline

- David Lines as Telegraph Boy

Production

Development

Towards the end of the war, Michael Balcon of Ealing Studios, was keen to "carry on the tradition that made British documentary film preeminent during the war. These were the days when we were inspired by the heroic deeds typical of British greatness."[2]

In 1944, Charles Frend and Sidney Cole pitched the idea of a film about the Scott expedition. Balcon was interested, so they wrote up a story treatment which Balcon approved. Ealing secured co-operation from Scott's widow (who would die in 1947).[2][3][4] Walter Meade wrote the first draft.[5][6]

The extensive number of interviews that were done with surviving team members and relatives from Scott's expedition were acknowledged at the start of the film with the credit:

"This film could not have been made without the generous co-operation of the survivors and the relatives of late members of Scott's Last Expedition. To them and to those many other persons and organisations too numerous to mention individually who gave such able assistance and encouragement, the producers express their deepest gratitude."

Casting

In 1947 it was announced that John Mills, then one of the biggest stars in Britain, would play the title role.[7][8]

"This is the most responsible thing I have done in films," said Mills. "I was only about four when the tragedy happened, but Scott has always been one of my heroes and it's jolly satisfying to feel that the job of helping to bring the great story of British enterprise and grit to the screen has fallen to me."[2] During the making of the film, Mills wore Scott's actual watch which had been recovered from his body.[9][10]

Filming

After three year's research for the film, cameraman Osmond Baradaile travelled 30,000 mi (48,000 km) and spent six months between 1946 and 1947 shooting footage in the Antarctic at Hope Bay as well as at South Shetland and the Orkneys.[11][4]

Filming started in June 1947 in Switzerland for four weeks, at the Jungfrau Mountain and the Aletsch Glacier. In October 1947 there was further nine weeks location filming in Norway, near Finse, which was used to represent the area near the South Pole. The bulk of the scenes were shot at the Hardanger Jokul.[4][12]

The film's unit transferred to Ealing Studios in London for three months of studio work.[13][14][15][16]

Release

The film was chosen for a Royal Command Film Performance in 1948.[17]

Reception

Scott of the Antarctic was the third most popular film at the British box office in 1949.[18][19] According to Kinematograph Weekly the 'biggest winner' at the box office in 1949 Britain was The Third Man with "runners up" being Johnny Belinda, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, Paleface, Scott of the Antarctic, The Blue Lagoon, Maytime in Mayfair, Easter Parade, Red River and You Can't Sleep Here.[20]

The film also performed well at the box office in Japan.[21]

Historical accuracy

Differences

There are several minor changes in the film compared to real events.

In the film, Scott receives a telegram in New Zealand, but does not read it for himself or to the crew until his ship is en route to the Antarctic. It says: "I am going south. Amundsen". Scott and his crew immediately comprehend that Amundsen is heading for the South Pole. In fact, Scott received this telegram a little earlier, in Australia, and Amundsen's true text was less clear: "Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic Amundsen." [Fram was Amundsen's ship.] As Amundsen had publicly announced he was going to the North Pole, the real Scott and his companions did not initially grasp Amundsen's ambiguous message, according to Tryggve Gran's diary (Gran was Scott's only Norwegian expedition member).

In the film, the Terra Nova disembarks Scott's team in the Antarctic, sails along the ice barrier without Scott and unexpectedly discovers Amundsen's Antarctic base camp. The ship therefore returns to Scott's base camp and informs Scott about Amundsen's presence in the vicinity. In fact, Scott was not at his base camp during this unscheduled return of his ship but was busy laying depots in the interior of the Antarctic.

In the film, just before reaching the South Pole, Scott's team sight a far-away flag, and realise the race is lost. In the next scene, the men arrive at Amundsen's empty tent flying a Norwegian flag at the Pole, and notice the paw prints of Amundsen's sledge-dogs. In reality, Scott and his men discovered the "sledge tracks and ski tracks going and coming and the clear trace of dogs' paws – many dogs" on the previous day when they came to a black flag Amundsen had left to mark his way back.

The film gives the impression that Scott starts to doubt at the South Pole whether he would manage to return to base camp safely, quoting his "Now for the run home and a desperate struggle. I wonder if we can do it" (after Jan 18th date, while actually he wrote this a day earlier, even before reaching Amundsen's tent). In fact, Scott wrote "…struggle to get the news through first" (both he and Amundsen had lucrative agreements with the media on exclusive interviews, but Scott now had little chance to beat Amundsen to the cablehead in Australia). This bit was however among those omitted from the published diary, which was discovered long after the film was produced.[22]

Expedition failures

Given that some 1912 expedition members were still alive and were consulted in the production process, the film carefully depicts the causes of the tragedy as they were considered in 1948. The film does not discuss or imply other factors that would harshly condemn the team's preparations or decisions of leadership.

- In Norway, Scott consults the veteran polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who urges Scott to rely only on dogs. Scott on the other hand insists on a variety of transport means, including motor sledges, ponies, and dogs. The historical background to Scott's portrayed reluctance is that on his 1904 expedition, Scott's dogs had died of disease while Ernest Shackleton in 1908 had nearly attained the South Pole using ponies.

- Scott's depicted fundraising speech is not effective and the government only gives him £20,000. To make the expedition possible anyway, he cancels one of his two planned ships, and settles on the dilapidated Terra Nova, a photo of which he optimistically shows to Wilson, who is unmoved. This scene reflects the real Apsley Cherry-Garrard's criticism over the lack of funds and the inappropriate ship in his book The Worst Journey in the World. (He also wrote that the calorie content of the planned food ration was totally inadequate for trekking 1,800 mi (2,900 km) across the Antarctic plateau; all party members were unable to replace the energy they were expending.)

- Arriving in Antarctic waters, the ship is briefly seen to fight its way through pack-ice. The parallel to the real expedition is that the ship was delayed for the unusual period of 20 days in the pack-ice, shortening the available season for preparations.

- Having ascended the glacier up to the polar plateau, Scott sends home one of the supporting parties, addressing its leader Atkinson ("Atch") with the following words "Bye Atch. Look out for us about the beginning of March. With any luck we will be back before the ship has to go." This paraphrases Scott's real order to the dog teams to assist him home to base camp around March 1 at latitude 82 degrees. The order was never carried out and so Scott and his men died on their way home at the end of March.[23]

- On the return journey from the pole, the men found that the stove oil canisters in the depots were not full. The seals were not broken so they speculate that the oil has evaporated.

References

- "Scott of the Antarctic (1948) – IMDb".

- "THE STARRY WAY". The Courier-mail. No. 3597. Queensland, Australia. 5 June 1948. p. 2. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Chips Rafferty saw Britain's idea-men". The Daily Telegraph. Vol. VIII, no. 6. New South Wales, Australia. 22 December 1946. p. 28. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "SCOTT of the ANTARCTIC". The Sunday Herald (Sydney). No. 6. New South Wales, Australia. 27 February 1949. p. 5 (Magazine Section). Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Hollywood star Milland to make English films". The Sun. No. 2209. New South Wales, Australia. 12 August 1945. p. 3 (SUPPLEMENT TO THE WEEK END MAGAZINE). Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Scott's Expedition To Be Filmed". The Mercury. Vol. CLXII, no. 23, 362. Tasmania, Australia. 20 October 1945. p. 11. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "FILM WORLD". The West Australian. Vol. 63, no. 18, 999. Western Australia. 6 June 1947. p. 20 (SECOND EDITION.). Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "CROSBY WAS BEST MONEY MAKER IN BRITAIN". The Mirror. Vol. 26, no. 1391. Western Australia. 15 January 1949. p. 14. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "VIVIEN HAS TROUBLE WITH HER HAT FOR AUSSIE". Truth. No. 2497. Queensland, Australia. 1 February 1948. p. 17. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- Mills, John (8 May 1948). "Bringing the South Pole to Britain: How we made the Scott film". Answers. London. 114 (2953): 3.

- "FILM WORLD". The West Australian. Vol. 63, no. 19, 059. Western Australia. 15 August 1947. p. 19. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- REALISM ON ICE: Scott Polar Movie Being Made in Norway Fjords, The New York Times 21 December 1947: X6.

- "BRITISH FILMS". The Sun. No. 2311. New South Wales, Australia. 27 July 1947. p. 18. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Frostbites Made To Measure For Stars". Truth. No. 3012. New South Wales, Australia. 12 October 1947. p. 54. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "John Mills in Scott Drama". The Mail (Adelaide). Vol. 36, no. 1, 861. South Australia. 24 January 1948. p. 3 (SUNDAY MAGAZINE). Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "NOTES ON FILMS". The Sunday Herald (Sydney). No. 25. New South Wales, Australia. 10 July 1949. p. 4 (Sunday Herald Features). Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "'Scott' command movie of 1948". The Mail (Adelaide). Vol. 37, no. 1, 900. South Australia. 30 October 1948. p. 3 (SUNDAY MAGAZINE). Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "TOPS AT HOME". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 31 December 1949. p. 4. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Thumim, Janet. "The popular cash and culture in the postwar British cinema industry". Screen. Vol. 32, no. 3. p. 258.

- Lant, Antonia (1991). Blackout : reinventing women for wartime British cinema. Princeton University Press. p. 232.

- "FILM SCENE ALONG THE BANKS OF THE THAMES: U.S. Industry Winner in Anglo-American Parley--Production Sheet in the Red Tax Takes Profits Freeze in Reverse Tom Brown". The New York Times. 20 August 1950. p. 83.

- Race for the South Pole. The Expedition Diaries of Scott and Amundsen. Roland Huntford. 2010, Continuum, London, New York.

- Evans, E.R.G.R (1949). South with Scott. London: Collins. pp. 187–188.

About the first week of February I should like you to start your third journey to the South, the object being to hasten the return of the third Southern unit [the polar party] and give it a chance to catch the ship. The date of your departure must depend on news received from returning units, the extent of the depot of dog food you have been able to leave at One Ton Camp, the state of the dogs, etc ... It looks at present as though you should aim at meeting the returning party about March 1 in Latitude 82 or 82.30

External links

- Scott of the Antarctic at the British Film Institute

- Scott of the Antarctic at the BFI's Screenonline

- Scott of the Antarctic at IMDb

- Review of film at Variety

- Scott of the Antarctic film page

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии