fiction.wikisort.org - Screenwriter

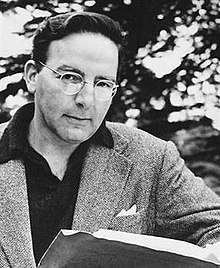

Cyril Raker Endfield (November 10, 1914 – April 16, 1995) was an American screenwriter, director, author, magician and inventor. Having been named as a Communist at a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing and subsequently blacklisted, he moved to the United Kingdom in 1953, where he spent the remainder of his career.[1]

Cy Endfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 10, 1914 Scranton, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 16, 1995 (aged 80) Shipston-on-Stour, Warwickshire, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1942–1979 |

Early life

Endfield was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, to a Jewish immigrant father whose business was hit hard by the Great Depression.[2] He attended Yale University.[3]

Career in the U.S.

Endfield began his career as a theatre director and drama coach, becoming a significant figure in New York's progressive theatre scene.[4] It was largely through a shared interest in magic that Orson Welles became aware of Endfield and recruited him as an apprentice for Mercury Productions (then based at RKO Pictures).[1] One of his independent films was Inflation (1942), a 15-minute commission for the Office of War Information that was rejected as being anti-capitalist.[3]

The debacle surrounding the production of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) ended with the expulsion of the Mercury team from the RKO lot. Endfield signed on as a contract director at MGM where he directed a variety of shorts (including the last films in the long-running Our Gang series), before freelancing on low-budget productions for Monogram and other independents.[5] He served in the Army during World War II.[3]

It was with the film noir The Underworld Story (1950), a United Artists independent production, that Endfield first received significant critical and studio attention. The film was a major leap from anything he had previously produced in regards to budget and social commentary, constituting a devastating attack on press corruption which could equally be taken as a wider attack on the McCarthyite ideology of the times.[6] He followed this with the film often cited as his masterpiece,[7][8][9][10] The Sound of Fury (aka Try And Get Me!) (1950), a lynching thriller based on a true story. Except for the lynching scene, the film was not well received by critics.[11] It was with these two films that Endfield's signature approach to character developed, pessimistic without being uncompassionate.[7]

Career in the United Kingdom

In 1951 Endfield was named as a Communist at a HUAC hearing. Subsequently blacklisted and without work, he moved to the United Kingdom in 1953, where, under various pseudonyms (to avoid complications with releases in the U.S.), he continued his career.[3] He would often cast fellow blacklistees in his films, such as Lloyd Bridges and Sam Wanamaker.[12][13] Three films – The Limping Man (1953), Impulse (1954), and Child in the House (1956) – list Charles de la Tour (a documentary filmmaker) as co-director because the ACT (Association of Cinematograph Technicians) insisted Endfield, who was not a full member of the union, could only direct in the UK if he had a British director on set as a standby.[14] Hell Drivers (1957) was the first project he released under his real name and earned him his first BAFTA nomination, for Best British Screenplay.[3] His 1961 film Mysterious Island featured special effects by Ray Harryhausen.[15]

One of his most notable films was Zulu (1964), a war epic depicting the Battle of Rorke's Drift in the Anglo-Zulu War of the 1870s. This was followed by Sands of the Kalahari (1965) with Susannah York.[3] After a few more independent productions he withdrew from directing films in 1971, his final film being Universal Soldier, in which he made a cameo appearance alongside Germaine Greer.[16] In 1979 he wrote the non-fiction book Zulu Dawn, which tells the story of the disastrous Battle of Isandlwana and the events which led up to the battle. A film adaptation of the book was released that same year, co-written by Endfield and directed by Douglas Hickox.[17][18]

Death

Endfield died in 1995 at the age of 80 at Shipston-on-Stour, in Warwickshire, England.[3] His body was buried at Highgate Cemetery in London.

Legacy

Endfield is co-credited with Chris Rainey for a pocket-sized/miniature computer with a chorded keypad that allows rapid typing without a bulky single-stroke keyboard. It functions like a musical instrument by pressing combinations of keys that he called a "Microwriter" to generate a full alphanumeric character set. It is still available, as "CyKey", for PC and Palm PDA, by Endfield's former partner, Chris Rainey and Bellaire Electronics. CyKey is named after Cy Endfield.[19]

British magician Michael Vincent credits Endfield as one of his biggest influences. The classic Cy Endfield's Entertaining Card Magic (1955), by Lewis Ganson, includes a variety of Endfield's creations in card magic.

Selected filmography

- Inflation (1942) (short) – director

- Radio Bugs (1944) (short) – director

- Tale of a Dog (1944) (short) – director

- Nostradamus IV (1944) (short) – director

- The Great American Mug (1945) (short) – director

- Magic on a Stick (1946) (short) – director

- Our Old Car (1946) (short) – director

- Joe Palooka, Champ (1946) – writer

- Mr Hex (1946) – writer

- Gentleman Joe Palooka (1946) – director, writer

- Stork Bites Man (1947) – director, writer

- Hard Boiled Mahoney (1947) – writer

- Sleep, My Love (1948) – writer (uncredited)

- The Argyle Secrets (1948) – director, writer, author of original radio play

- Joe Palooka in the Big Fight (1949) – director, writer

- Joe Palooka in the Counterpunch (1949) – writer

- The Underworld Story (1950) – director, writer

- The Sound of Fury (1950) – director, writer (uncredited)

- Tarzan's Savage Fury (1952) – director

- The Limping Man (1953) – director

- Impulse (1954) – director, writer

- Crashout (1955) – writer (uncredited)

- The Master Plan (1955) – director, writer

- The Secret (1955) – director, writer

- Child in the House (1956) – director, writer

- Colonel March of Scotland Yard (1956) – director

- Hell Drivers (1957) – director, writer

- Curse of the Demon (1957) – final screenplay (uncredited)

- Sea Fury (1958) – director, writer

- Jet Storm (1959) – director, writer

- Mysterious Island (1961) – director

- Zulu (1964) – director, writer, producer

- Hide and Seek (1964) – director

- Sands of the Kalahari (1965) – director, writer, producer

- De Sade (1969) – director

- Universal Soldier (1971) – director, writer

- Zulu Dawn (1979) – writer

References

- Trevor Willsmer (April 21, 1995). "OBITUARY : Cy Endfield - People - News". The Independent. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- Jim Burns. Review— THE MANY LIVES OF CY ENDFIELD: FILM NOIR, THE BLACKLIST, AND ZULU. Penniless Press.

- The Associated Press (May 2, 1995). "Cy Endfield, 80; Blacklisted Director". The New York Times.

- "Cy Endfield - MagicPedia". Geniimagazine.com. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- "BFI Screenonline: Endfield, Cy (1914-95) Biography". Screenonline.org.uk. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- "DVD Savant Review: The Underworld Story". Dvdtalk.com. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- "Potent Pessimism [on Cy Endfield". Jonathan Rosenbaum. July 10, 1992. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- "The Sound of Fury". MoMA. November 6, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- "Try and Get Me (a.k.a. The Sound of Fury) (1950); Repeat Performance (1947) | UCLA Film & Television Archive". Cinema.ucla.edu. March 4, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- "Cy Endfield | American Cinematheque". Americancinemathequecalendar.com. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- Bosley Crowther (May 7, 1951). "THE SCREEN IN REVIEW; 'Try and Get Me,' Based on Novel, 'Condemned,' Has Frank Lovejoy and Kathleen Ryan in Leads". The New York Times.

- "Abbreviated View of Movie Page". Afi.com. December 11, 1953. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- "The Secret | BFI | BFI". Explore.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- Brian Neve, The Many Lives of Cy Endfield: Film Noir, the Blacklist, and Zulu (University of Wisconsin Press, 2015), pp105-106

- "Mysterious Island (1961)". Tcm.com. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- "Cy Endfield | shadowplay". Dcairns.wordpress.com. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- Endfield, Cy (August 1, 1980). Zulu Dawn: Cy Endfield: 9780523411484: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 0523411480.

- "Empire's Zulu Dawn Movie Review". Empireonline.com. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- bellaire.co.uk

External links

- Cy Endfield at IMDb

- Cy Endfield biography and credits at the BFI's Screenonline

На других языках

[de] Cy Endfield

Cyril Raker Endfield (* 10. November 1914 in Scranton, Pennsylvania; † 16. April 1995 in Shipston-on-Stour, England) war ein US-amerikanischer Regisseur, Zauberkünstler und Erfinder, der als Opfer der McCarthy-Ära in Großbritannien arbeitete. Zudem war er auch als Drehbuchautor tätig. Sein populärster Film ist Zulu.- [en] Cy Endfield

[ru] Эндфилд, Сай

Сай Эндфилд (англ. Cy Endfield, имя при рождении — Cyril Raker Endfield) (10 ноября 1914 года — 16 апреля 1995 года) — американский сценарист, кинорежиссёр, театральный режиссёр, писатель, иллюзионист и изобретатель, с 1953 года проживавший в Великобритании[2].Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии