fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

Etta Federn-Kohlhaas (April 28, 1883 – May 9, 1951) or Marietta Federn, also published as Etta Federn-Kirmsse and Esperanza, was a writer, translator, educator and important woman of letters in pre-war Germany.[1][2] In the 1920s and 1930s, she was active in the Anarcho-Syndicalism movement in Germany and Spain.

Etta Federn | |

|---|---|

Etta Federn in Barcelona, 1934 | |

| Born | April 28, 1883 Vienna, Austria |

| Died | May 9, 1951 (aged 68) Paris, France |

| Pen name | Etta Federn-Kohlhaas, Marietta Federn, Etta Federn-Kirmsse, Esperanza |

| Occupation | Writer, translator |

| Genres | Literary biography, women's history |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarcha-feminism |

|---|

|

|

Raised in Vienna, she moved in 1905 to Berlin, where she became a literary critic, translator, novelist and biographer. In 1932, as the Nazis rose to power, she moved to Barcelona, where she joined the anarchist-feminist group Mujeres Libres, (Free Women),[3] becoming a writer and educator for the movement. In 1938, toward the end of the Spanish Civil War, she fled to France. There, hunted by the Gestapo as a Jew and a supporter of the French Resistance, she survived World War II in hiding.[4]

In Germany, she published 23 books, among them translations from the Danish, Russian, Bengali, Ancient Greek, Yiddish and English. She also published two books while living in Spain.

The story of Etta Federn and her two sons inspired the 1948 play Skuggan av Mart [5] (Marty's Shadow), by the important Swedish writer Stig Dagerman, who published novels, plays and journalism before committing suicide at age 31. The play he based loosely on Federn was first performed at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm, and has since played in several countries, including Ireland, the Netherlands, Cyprus and France. Marty's Shadow was first performed in the U.S. in 2017, by the August Strindberg Repertory Theatre in New York City.[6]

Personal life

Raised in an assimilated Jewish family in Vienna, Etta Federn was the daughter of suffragist Ernestine (Spitzer)[7] and Dr. Salomon Federn, a prominent physician and pioneer in the monitoring of blood pressure.[8][9]

Her brother Paul Federn, a psychoanalyst, was an early follower and associate of Sigmund Freud. An expert on ego psychology and the treatment of psychosis, he served as vice president of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

Her brother Walther Federn was an important economic journalist in Austria before Hitler came to power. Her brother Karl Federn was a lawyer who, after fleeing to the UK, became known for his anti-Marxist writings.

Her sister Else Federn was a social worker in Vienna, active in the Settlement Movement. A park in Vienna was named for her in 2013.[10][11]

Etta Federn's first husband was Max Bruno Kirmsse, a German teacher of children with mental disabilities. Her second husband was Peter Paul Kohlhaas, an illustrator.[12] She had two sons, Hans and Michael, one from each marriage. Her older son, known as Capitaine Jean in the French Resistance, was murdered by French collaborators in 1944.[13][14]

Career

In Vienna and Berlin, Etta Federn studied literary history, German philology and Ancient Greek.[2] She worked in many genres, publishing articles, biographies, literary studies and poetry. She also wrote a young adult novel, Ein Sonnenjahr (A Year of Sun), as well as an adult novel that remained unpublished.

As a journalist, she was a literary critic for the Berliner Tageblatt, an influential liberal newspaper. She wrote biographies of Dante Alighieri and Christiane Vulpius (wife of Johann von Goethe).[2] In 1927, she published a biography of Walther Rathenau, the liberal Jewish Foreign Minister of Germany, who had been assassinated in 1922 by anti-Semitic right-wing terrorists. Her biography was reviewed by Gabriele Reuter for the New York Times, which called Federn's account "amazingly lucid and precise" and said it "gives a beautifully clear idea of [Rathenau's] life."[15] Following the book’s publication, Federn became the target of Nazi death threats.[3]

During the 1920s, Federn became part of a circle of anarchists, including Rudolf Rocker, Mollie Steimer, Senya Fleshin, Emma Goldman, and Milly Witkop Rocker, who would become her close friend.[16][17] She contributed to various anarchist newspapers and journals related to the Free Workers' Union of Germany.[18]

In Berlin, Federn also met and translated several Polish-born Jewish poets who wrote in Yiddish. In 1931, her translation of the Yiddish poetry collection Fischerdorf (Fishing Village) by Abraham Nahum Stencl was published. Thomas Mann gave the book a favorable review, admiring Stencl's "passionate poetic emotion."[19] (The work would soon be destroyed in the Nazi book burnings).

In 1932, Federn left Berlin, realizing that under the Nazis she would no longer be able to publish her writing. She moved with her sons to Barcelona, Spain, where she joined the anarchist movement Mujeres Libres (Free Women), which provided such services as maternity centers, daycare centers, and literacy training to women. She learned Spanish and became director of four progressive schools in the city of Blanes, educating both teachers and children in secular values and antimilitarism.[3] Starting in 1936, she also published a number of articles in the movement's women-run magazine, also called Mujeres Libres.[20]

Like many anarchist women, she believed in the importance of literacy for women, in birth control and sexual freedom,[21] and in the power of educated women to be good mothers. She wrote: "Educated mothers relate their own experiences and sufferings to their children; they intuitively understand their feelings and expressions. They are good educators, as they are also friends of the children they educate."[22]

In 1938, as Francisco Franco's fascists bombed Barcelona and defeated the left, Federn fled to France, where she was held in internment camps as a foreign refugee. She spent the war in hiding in Lyon, at times in a monastery, and did translation work for the French Resistance.[14] She spent her final years in Paris, supported in part by her relatives in the USA and doing palm readings based on her psychological insights. Because her son was killed as a Resistance fighter, she was awarded French citizenship.[17]

Biographies

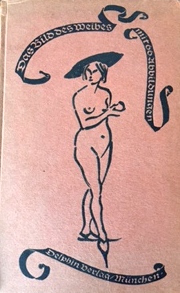

- Christiane von Goethe: Ein Beitrag zur Psychologie Goethes (Christiane von Goethe: A Contribution to Goethe's Psychology). Munich: Delphin. 1916.

- Goethe: Sein Leben der reifenden Jugend erzählt. (Goethe: His Life Story for Young Adults). Stuttgart: Union Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft. 1922.

- Dante: Ein Erlebnis für werdende Menschen (Dante: An Experience for the Expecant). Stuttgart: Union Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft. 1923.

- Walther Ratenau: Sein Leben und Wirken (Walter Rathenau: His Life and Work). Dresden: Reissner. 1927.

- Mujeres de las revoluciones (Revolutionary Women). Barcelona: Mujeres libres. 1936. Reissued in German as Etta Federn: Revolutionär auf ihre Art, von Angelica Balabanoff bis Madame Roland, 12 Skizzen unkonventioneller Frauen (Etta Federn: Revolutionary in her Way: From Angelica Balabanoff to Madame Roland, 12 Sketches of Unconventional Women), edited and translated by Marianne Kröger, 1997.

Translations

- H.C. Andersens Märchen, Tales of Hans Christian Andersen, translated from the Danish, 1923. Reissued 1952.

- Shakespeare-Lieder, Sonnets of William Shakespeare, translated from the English, 1925.

- Wege der liebe : drei Erzählungen (The Ways of Love: Three Stories), by Alexandra Kollontai, translated from the Russian, 1925. Reissued 1982.

- Gesichte, Poems of Samuel Lewin, translated from the Yiddish, 1928.

- Fischerdorf (Fishing Village), Poems of A. N. Stencl, translated from the Yiddish, 1931.

- Sturm der Revolution (The Storm of Revolution), Poems of Saumyendranath Tagore, translated from the Bengali, 1931.

- Anakreon, Poems of Anacreon, translated from the Ancient Greek, 1935.

References

- "ARIADNE – Projekt "Frauen in Bewegung" – Etta Federn, online bibliography". www.onb.ac.at. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- Wininger, Salomon (1935). "Federn-Kohlhaas, Etta". Grosse Jüdische National-Biographie. p. 494.

- Heath, Nick. "Federn, Marietta aka Etta 1883–1951". Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Kröger, Marianne, ed. (1997). Etta Federn: Revolutionär auf ihre Art: Von Angelica Balabanoff bis Madame Roland, 12 Skizzen unkonventioneller Frauen (Etta Federn: Revolutionary in Her Way: From Angelica Balabanoff to Madame Roland, 12 Sketches of Unconventional Women). Psychosozial-Verlag.

- "The Shadow of Mart". Stig Dagerman, Swedish Writer and Journalist (1923–1954). Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- "Stig Dagerman's 'Marty's Shadow'". Archived from the original on 2017-03-17. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "Ernestine Spitzer". Wien Geschichte Wiki. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Federn, Joseph Salomon". Austria-Forum. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Ernst, Rosita Anna (2008). Die Familie Federn im Wandel der Zeit – Eine biographische und werksgeschichtliche Analyse einer psychoanalytisch orientierten Familie. GRIN. pp. 33–35.

- Rastl, Charlotte. "Else Federn". Unlearned Lessons. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- "Queer Places: Else-Federn-Park". Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- Kröger, Marianne (2009). "Jüdische Ethik" und Anarchismus im Spanischen Bürgerkrieg. Peter Lang. p. 166.

- "The Shadow of Mart". Stig Dagerman, Swedish Writer and Journalist (1923–1954). Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Allemagne, Espagne, France… le long combat pour la liberté d'Etta Federn". La Feuille Charbinoise. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Reuter, Gabriele (20 November 1927). "Rathenau in a New German Biography". New York Times. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "Etta Federn". Anarcopedia. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Etta Federn — eine jüdisch-libertäre Pionierin « Bücher – nicht nur zum Judentum". buecher.hagalil.com. 17 June 2009. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- "Etta Federn (1883–1951) und die Mujeres Libres | gwr 225 | januar 1998". www.graswurzel.net. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- Valencia, Heather. "Stencl's Berlin Period". Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Ackelsberg, Martha (2005). Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. AK Press. pp. 266–268. ISBN 9781902593968.

- Herzog, Dagmar (2011). Sexuality in Europe: A Twentieth-Century History. Cambridge University Press. p. 51.

- Kaymakçioglu, Göksu. ""STRONG WE MAKE EACH OTHER": Emma Goldman, The American Aide to Mujeres Libres During the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939" (PDF). Retrieved 3 December 2015.

Further reading

- Marianne Kröger: Etta Federn (1883–1951): Befreiende Dichtung und libertäre Pädagogik in Deutsche Kultur−jüdische Ethik : abgebrochene Lebenswege deutsch-jüdischer Schriftsteller nach 1933 (German Culture−Jewish Ethics: Broken Life-paths of German-Jewish writers after 1933), edited by Renate Heuer and Ludger Heid, Frankfurt: Campus, 2011. pp. 115–140.

- Marianne Kröger: "Jüdische Ethik" und Anarchismus im Spanischen Bürgerkrieg: Simone Weil−Carl Einstein−Etta Federn ("Jewish Ethics" and Anarchism in the Spanish Civil War: Simone Weil−Carl Einstein−Etta Federn), Peter Lang, 2009.

- Martha Ackelsberg: Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women, AK Press, 2005.

- Lo Dagerman and Nancy Pick: Skuggorna vi bär: Stig Dagerman möter Etta Federn i Paris 1947 (The Shadows We Bear: Stig Dagerman Meets Etta Federn in Paris, 1947), Norstedts, Sweden, 2017. Also published in France as Les ombres de Stig Dagerman, Maurice Nadeau, 2018; and in English, under the title The Writer and Refugee.

External links

- Entry in Ariadne, online Biography (in German)

- Skuggorna vi bär, biographical book about Stig Dagerman and Etta Federn, Norstedts, 2017 (in Swedish)

- Les ombres de Stig Dagerman, biographical book about Stig Dagerman and Etta Federn, Maurice Nadeau, 2018 (in French)

На других языках

[de] Etta Federn-Kohlhaas

Etta Federn-Kohlhaas (* 28. April 1883 in Wien; † 9. Mai 1951 in Paris) hieß eigentlich Marietta Federn und war eine österreichische Schriftstellerin, Übersetzerin und anarchosyndikalistische Aktivistin sowie Mitglied der französischen Résistance. Sie publizierte auch als Etta Kirmsse oder Esperanza und gilt als frühe und bedeutende Publizistin in dem Umfeld.[1][2]- [en] Etta Federn

[es] Etta Federn

Etta Federn-Kohlhaas o Marietta Federn, también conocida como Etta Federn-Kirmsse y Esperanza, (Viena, 28 de abril de 1883 – París, 9 de mayo de 1951) fue una escritora, traductora, pedagoga, militante anarquista, anarcosindicalista y anarcofeminista austriaca y una importante mujer de letras en la Alemania de antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial.[1] En las décadas de 1920 y 1930, participó activamente en el movimiento anarcosindicalista en Alemania y España.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии