fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose[1] CSI CIE FRS[2][3][4] (/boʊs/;,[5] IPA: [dʒɔɡodiʃ tʃɔndro boʃu]; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937)[6] was a biologist, physicist, botanist and an early writer of science fiction.[7] He pioneered the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contributions to botany, and was a major force behind the expansion of experimental science on the Indian subcontinent.[8] IEEE named him one of the fathers of radio science.[9] Bose is considered the father of Bengali science fiction. He invented the crescograph, a device for measuring the growth of plants. A crater on the moon was named in his honour.[10] He founded Bose Institute, a premier research institute in India and also one of its oldest. Established in 1917, the institute was the first interdisciplinary research centre in Asia.[11] He served as the Director of Bose Institute from its inception until his death.

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose CSI CIE FRS | |

|---|---|

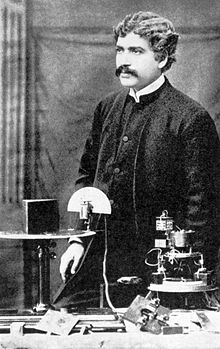

Jagadish Chandra Bose in Royal Institution, London, 1897 | |

| Born | 30 November 1858 Bikrampur, Bengal Presidency, British India (now Munshiganj, Bangladesh) |

| Died | 23 November 1937 (aged 78) |

| Alma mater | St. Xavier's College, Calcutta (BA) Christ's College, Cambridge (BA) University College London (BSc, DSc) |

| Known for | Millimetre waves Radio Crescograph Contributions to plant biology Crystal radio Crystal detector |

| Spouse | Abala Bose |

| Awards | Companion of The Order of the Indian Empire (CIE) (1903) Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI) (1911) Knight Bachelor (1917) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, biophysics, biology, botany |

| Institutions | University of Calcutta University of Cambridge University of London |

| Academic advisors | John Strutt (Rayleigh) |

| Notable students | Satyendra Nath Bose Meghnad Saha Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis Sisir Kumar Mitra Debendra Mohan Bose |

| Signature | |

Born in Munshiganj, Bengal Presidency, during British governance of India (now in Bangladesh),[6] Bose graduated from St. Xavier's College, Calcutta (now Kolkata, West Bengal, India). He attended the University of London to study medicine, but had to give it up due to health problems. Instead, he conducted research with Nobel Laureate Lord Rayleigh at the University of Cambridge. Bose returned to India to join the Presidency College of the University of Calcutta as a professor of physics. There, despite racial discrimination and a lack of funding and equipment, Bose carried on his scientific research. He made progress in his research into radio waves in the microwave spectrum and was the first to use semiconductor junctions to detect radio waves.

Bose made pioneering discoveries in plant physiology. He used his own invention, the crescograph, to measure plant response to various stimuli and proved parallelism between animal and plant tissues. Bose filed for a patent for one of his inventions because of peer pressure, but he was generally critical of the patent system. To facilitate his research, he constructed automatic recorders capable of registering extremely slight movements; these instruments produced some striking results, such as quivering of injured plants, which Bose interpreted as a power of feeling in plants. His books include Response in the Living and Non-Living (1902) and The Nervous Mechanism of Plants (1926). He spent the last years of his life in Giridih. Here he lived in the house located near Jhanda Maidan. This building was named Jagdish Chandra Bose Smriti Vigyan Bhavan. It was inaugurated on 28 February 1997 by the then Governor of Bihar AR Kidwai.[12] In a 2004 BBC poll to name the Greatest Bengali of all time, Bose placed seventh.[13]

Early life and education

Jagadish Chandra Bose was born in a Bengali Kayastha family in Munsiganj (Bikrampur), Bengal Presidency (present-day Bangladesh)[6][14] on 30 November 1858, to Bama Sundari Bose and Bhagawan Chandra Bose. His father was a leading member of the Brahmo Samaj and worked as a civil servant with the title Deputy Magistrate and Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP) in several places, including Faridpur and Bardhaman.[15][16]

Bose's father sent Bose to a Bengali language school for his early education, as it was important to him that his son should study in his native language and culture before studying in English. Speaking at the Bikrampur Conference in 1915, Bose described the effect this early education had on him:

At that time, sending children to English schools was an aristocratic status symbol. In the vernacular school, to which I was sent, the son of the Muslim attendant of my father sat on my right side, and the son of a fisherman sat on my left. They were my playmates. I listened spellbound to their stories of birds, animals, and aquatic creatures. Perhaps these stories created in my mind a keen interest in investigating the workings of Nature. When I returned home from school accompanied by my school fellows, my mother welcomed and fed all of us without discrimination. Although she was an orthodox old-fashioned lady, she never considered herself guilty of impiety by treating these 'untouchables' as her own children. It was because of my childhood friendship with them that I could never feel that there were 'creatures' who might be labeled 'low-caste', I never realized that there existed a 'problem' common to the two communities, Hindus and Muslims.[16]

Bose joined the Hare School in Kolkata in 1869, followed by St. Xavier's School, also in Kolkata. In 1875, he passed the entrance examination of the University of Calcutta and was admitted to St. Xavier's College, Kolkata. There, he met Jesuit Father Eugene Lafont, who played a significant role in developing his interest in natural sciences.[16][17] He received a BA from the University of Calcutta in 1879.[15]

Bose wanted to follow his father into the Indian Civil Service, but his father forbid it, saying his son should be a scholar who would “rule nobody but himself.”[18] Bose went to England to study medicine at the University of London, but had to quit because of allergies & ill health, possibly worsened by the chemicals used in the dissection rooms.[19][self-published source][15]

Through the recommendation of Anandamohan Bose, his brother-in-law and the first Indian Wrangler at the University of Cambridge, Bose secured admission in Christ's College, Cambridge to study natural sciences. In 1884 he received a BA (Natural Sciences Tripos) from the University of Cambridge[17] as well as a BSc from the University College London affiliated under University of London in 1883.[20][21]

Among Bose's teachers at Cambridge were Lord Rayleigh, Michael Foster, James Dewar, Francis Darwin, Francis Balfour, and Sidney Vines. While at Cambridge, he met University of Edinburgh student Prafulla Chandra Roy, with whom he became intimate friends.[15][16] In 1887, Bose married feminist and social worker Abala Bose.[22]

Professorship at Presidency College

After obtaining a degree from the University of Cambridge Bose returned to India. Henry Fawcett had given Bose an introduction to Lord Ripon, the Viceroy of India, who recommended him for a post to the Director of Public Instruction in Kolkata. In those days such posts in the Imperial Education Service were usually reserved for Europeans. Bose was appointed as an officiating professor of physics at Presidency College. Although the principal Charles Henry Tawney and Director of Education Alfred Woodley Croft were reluctant to appoint him, Bose took up his post in January of 1885.[23][24]

At that time, an Indian professor was paid two thirds the salary of an European and since his appointment was considered temporary and his salary was further halved, making his salary one-third that of his European peers. As a protest, Bose did not accept his salary and worked without remuneration for the first three years at Presidency College.

He was popular among the students for his teaching style and demonstration of experiments. He got rid of the roll call. After three years’ work in this temporary post, the value of his professorial work was recognized by the principal Tawney and the director Croft, making Bose’s appointment permanent, with retrospective effect.[25] Bose received his full pay for the last three years in a lump sum. But another source states that his appointment was made permanent on 21 September 1903, some 8 years after his joining the college.[26]

Bose used his own money to fund his different research projects as well as receiving funding and support from the social activist nun Sister Nivedita.[27]

Microwave radio research

Bose became interested in radio following the 1894 publication of British physicist Oliver Lodge's demonstrations on how to transmit and detect radio waves.[28] He began his own research in the new field in November 1894, setting up his equipment in small 20 ft sq room at Presidency College.[24] Wanting to study the light-like properties of radio waves, hard to study using long radio waves, he managed to reduce the waves to the millimetre level (in the microwave range of about 5 mm wavelength).[28]

Bose’s research was not initially appreciated by his department at the college. They felt he should focus only on teaching and that research involved neglect of his duties as a teacher, in spite of Bose giving 26 hours of weekly lectures. Later, when interest was generated in the wider scientific community, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal proposed a research post to help Bose. But this scheme was withdrawn when Bose voted against the government’s stance during a university meeting. The Lieutenant-Governor persevered to have a Rs.2500 annual grant issued. Despite this Bose found it hard to find time for research due to his teaching duties.

Bose submitted his first scientific paper, "On polarisation of electric rays by double-refracting crystals," to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in May 1895. He submitted his second paper, "On a new electro-polariscope," to the Royal Society of London in October 1895, and it was published by The Electrician in December 1895. This may have been the first papers to be published by an Indian in western scientific periodicals.[29] The paper described Bose's plans for a coherer, a term coined by Lodge referring to radio wave receivers, which he intended to "perfect" but never patented. The paper was well received by The Electrician and The Englishman, which in January 1896 (commenting on how this new type of wall and fog penetrating "invisible light" could be used in lighthouses) wrote:[28]

Should Professor Bose succeed in perfecting and patenting his ‘Coherer’, we may in time see the whole system of coast lighting throughout the navigable world revolutionised by a Bengali scientist working single handed in our Presidency College Laboratory.

In November 1895 at a public demonstration at the Town Hall of Kolkata, Bose showed how the millimetre range wavelength microwaves could travel through the human body (of Lieutenant Governor Sir William Mackenzie), and over a distance 23 metres through two intervening walls where they trigger apparatus he had set up to ring a bell and ignited gunpowder in a closed room.[30][24][31]

Wanting to meet other scientists in Europe, Bose was given a six month scientific deputation in 1896.[32] Bose went to London on a lecture tour and met Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, who had been developing a radio wave wireless telegraphy system for over a year and was trying to market it to the British post service. He was also congratulated by William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin and received an honorary Doctor of Science ( DSc) from the University of London.[33][17] In an interview, Bose expressed his disinterest in commercial telegraphy and suggested others use his research work.

In 1899, Bose announced the development of an "iron-mercury-iron coherer with telephone detector" in a paper presented at the Royal Society, London.[34]

Place in radio development

Bose's work in radio microwave optics was specifically directed towards studying the nature of the phenomenon and was not an attempt to develop radio into a communication medium.[35] His experiments took place during this same period (from late 1894 on) when Guglielmo Marconi was making breakthroughs on a radio system specifically designed for wireless telegraphy[36] and others were finding practical applications for radio waves, such as Russian physicist Alexander Stepanovich Popov radio wave based lightning detector, also inspired by Lodge's experiment.[37] Although Bose's work was not related to communication he, like Lodge and other laboratory experimenters, probably had an influence on other inventors trying to develop radio as communications medium.[37][38][39] Bose was not interested in patenting his work and openly revealed the operation of his galena crystal detector in his lectures. A friend in the US persuaded him to take out a US patent on his detector but he did not actively pursue it and allowed it to lapse."[15]

Bose was the first to use a semiconductor junction to detect radio waves, and he invented various now-commonplace microwave components.[37] In 1954, Pearson and Brattain gave priority to Bose for the use of a semi-conducting crystal as a detector of radio waves.[37] In fact, further work at millimetre wavelengths was almost non-existent for the following 50 years. In 1897, Bose described to the Royal Institution in London his research carried out in Kolkata at millimetre wavelengths. He used waveguides, horn antennas, dielectric lenses, various polarisers and even semiconductors at frequencies as high as 60 GHz.[37] Much of his original equipment is still in existence, especially at the Bose Institute in Kolkata. A 1.3 mm multi-beam receiver now in use on the NRAO 12 Metre Telescope, Arizona, US, incorporates concepts from his original 1897 papers.[37]

Sir Nevill Mott, Nobel Laureate in 1977 for his own contributions to solid-state electronics, remarked that "J.C. Bose was at least 60 years ahead of his time. In fact, he had anticipated the existence of P-type and N-type semiconductors."[37]

Plant research

Bose conducted most of his studies in plant research on Mimosa pudica and Desmodium gyrans plants. His major contribution in the field of biophysics was the demonstration of the electrical nature of the conduction of various stimuli (e.g., wounds, chemical agents) in plants, which were earlier thought to be of a chemical nature. In order to understand the heliotropic movements of plants (the movement of a plant towards a light source), Bose invented a torsional recorder. He found that light applied to one side of the sunflower caused turgor to increase on the opposite side.[40][non-primary source needed] These claims were later proven experimentally.[41][non-primary source needed][original research?] He was also the first to study the action of microwaves in plant tissues and corresponding changes in the cell membrane potential. He researched the mechanism of the seasonal effect on plants, the effect of chemical inhibitors on plant stimuli and the effect of temperature.

Study of metal fatigue and cell response

Bose performed a comparative study of the fatigue response of various metals and organic tissue in plants. He subjected metals to a combination of mechanical, thermal, chemical, and electrical stimuli and noted the similarities between metals and cells. Bose's experiments demonstrated a cyclical fatigue response in both stimulated cells and metals, as well as a distinctive cyclical fatigue and recovery response across multiple types of stimuli in both living cells and metals.

Bose documented a characteristic electrical response curve of plant cells to electrical stimulus, as well as the decrease and eventual absence of this response in plants treated with anaesthetics or poison. The response was also absent in zinc treated with oxalic acid. He noted a similarity in reduction of elasticity between cooled metal wires and organic cells, as well as an impact on the recovery cycle period of the metal.[42][43][non-primary source needed]

Science fiction

In 1896, Bose wrote Niruddesher Kahini (The Story of the Missing One), a short story that was later expanded and added to Abyakta (অব্যক্ত) collection in 1921 with the new title Palatak Tuphan (Runaway Cyclone). It was one of the first works of Bengali science fiction.[44][45]

Bose Institute

In 1917 Bose established the Bose Institute in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Bose served as its Director for its first twenty years until his death. Today it is a public research institute of India and also one of its oldest. Bose in his inaugural address on 30 November 1917 dedicated the institute to the nation saying:

I dedicate today this Institute—not merely a Laboratory but a Temple. The power of physical methods applies to the establishment of that truth which can be realised directly through our senses, or through the vast expansion of the perceptive range by means of artificially created organs... Thirty-two years ago I chose the teaching of science as my vocation. It was held that by its very peculiar constitution, the Indian mind would always turn away from the study of Nature to metaphysical speculations. Even had the capacity for inquiry and accurate observation been assumed to be present, there were no opportunities for their employment; there were neither well-equipped laboratories nor skilled mechanicians. This was all too true. It is not for man to complain of circumstances, but bravely to accept, to confront and to dominate them; and we belong to that race which has accomplished great things with simple means.[46][47]

Personal views

Philosophical views

As a child Bose was very impressed by the character of Karna, from Mahabharata. Talking about Karna Bose said:

He always played and fought fair! So his life, though a series of disappointments and defeats to the very end - his slaying by Arjuna - appealed to me as a boy as the greatest of triumphs.

He identified Karna with the character of his father regarding whom he said:

Always in struggle for the uplift of the people, yet with so little success, such frequent failures, that to most he seemed a failure. All this too gave me a lower and lower idea of all worldly success - how small its so-called victories are! - and higher and higher idea of conflict and defeat; and of true success born of defeat. In such ways I have come to feel one with the highest spirit of my race; with every fibre thrilling with the emotion of the past. That is its noblest teaching - that the only real and spiritual advantage is to fight fair, never to take crooked ways, but keep to the straight path, whatever be in the way.[48]

Legacy and honors

![Acharya Bhavan, the residence of J C Bose built in 1902, was turned into a museum.[49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Acharya_Bhavan_-_Kolkata_2009-11-07_2938.JPG/170px-Acharya_Bhavan_-_Kolkata_2009-11-07_2938.JPG)

Bose's place in history has now been re-evaluated. His work may have contributed to the development of radio communication.[34] He is also credited with discovering millimetre length electromagnetic waves and being a pioneer in the field of biophysics.[50]

Many of his instruments are still on display and remain largely usable now, over 100 years later. They include various antennas, polarisers, and waveguides, which remain in use in modern forms today.

To commemorate his birth centenary in 1958, the JBNSTS scholarship programme was started in West Bengal. In the same year, India issued a postage stamp bearing his portrait.[51] The same year Acharya Jagdish Chandra Bose, a documentary film directed by Pijush Bose, was released. It was produced by the Government of India's Films Division.[52][53] Films Division also produced another documentary film, again titled Acharya Jagdish Chandra Bose, this time directed by the prominent Indian filmmaker Tapan Sinha.[54]

On 14 September 2012, Bose's experimental work in millimetre-band radio was recognised as an IEEE Milestone in Electrical and Computer Engineering, the first such recognition of a discovery in India.[55]

On 30 November 2016, Bose was celebrated in a Google Doodle on the 158th anniversary of his birth.[56]

The Bank of England has decided to redesign the 50 UK Pound currency note with a prominent scientist. Jagadish Chandra Bose has been featured in that nomination list for his pioneering work on Wifi technology.[57][58][59]

- The J.C. Bose University of Science and Technology, YMCA, named in his honour.

- Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE, 1903)

- Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI, 1912)

- Knight Bachelor (1917)

- Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS, 1920)[4]

- Member of the Vienna Academy of Sciences, 1928

- President of the 14th session of the Indian Science Congress in 1927.[60]

- Member of Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters in 1929.

- Member of the League of Nations' Committee for Intellectual Cooperation (from 1924 to 1931)[61]

- Founding fellow of the National Institute of Sciences of India (now the Indian National Science Academy)

- The Indian Botanic Garden was renamed in his honour as the Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden on 25 June 2009.[62]

- In 2004, Bose was ranked number 7 in BBC's poll of the Greatest Bengali of all time.[13]

Publications

- Journals

- Nature published about 27 papers.

- Bose J.C. (1902). "On Electromotive Wave accompanying Mechanical Disturbance in Metals in Contact with Electrolyte". Proc. R. Soc. 70 (459–466): 273–294. Bibcode:1902RSPS...70..273C. doi:10.1098/rspl.1902.0029.

- Bose J.C. (1902). "Sur la réponse électrique de la matière vivante et animée soumise à une excitation — Deux procédés d'observation de la réponse de la matière vivante". Journal de Physique. 4 (1): 481–491.

- Books

- Response in the Living and Non-living, 1902

- Plant response as a means of physiological investigation, 1906

- Comparative Electro-physiology: A Physico-physiological Study, 1907

- Researches on Irritability of Plants, 1913

- Life Movements in Plants (vol.1), First Published 1918, Reprinted 1985

- Life Movements in Plants, Volume II, 1919

- Physiology of the Ascent of Sap, 1923

- The physiology of photosynthesis, 1924

- The Nervous Mechanism of Plants, 1926

- Plant Autographs and Their Revelations, 1927

- Growth and tropic movements of plants, 1929

- Motor mechanism of plants, 1928

- Other

- J.C. Bose, Collected Physical Papers. New York, N.Y.: Longmans, Green and Co., 1927

- Abyakta (Bengali), 1922

Notes

- Page 3597 of Issue 30022. The London Gazette. (17 April 1917). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Page 9359 of Issue 28559. The London Gazette. (8 December 1911). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Page 4 of Issue 27511. The London Gazette. (30 December 1902). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Saha, M. N. (1940). "Sir Jagadis Chunder Bose. 1858–1937". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 3 (8): 2–12. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1940.0001. S2CID 176697911.

- "Bose". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Editorial Board (2013). Sir Jagdish Chandra Bose. Edinburgh, Scotland: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59339-292-5.

- "A versatile genius". Frontline. Vol. 21, no. 24. The Hindu. 20 November 2004.

- Chatterjee, Santimay and Chatterjee, Enakshi, Satyendranath Bose, 2002 reprint, p. 5, National Book Trust, ISBN 81-237-0492-5

- Sen, A. K. (1997). "Sir J.C. Bose and radio science". Microwave Symposium Digest. IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium. Denver, CO: IEEE. pp. 557–560. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602854. ISBN 0-7803-3814-6.

- Bose (crater)

- "Bose Institute | History". jcbose.ac.in. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- "Giridih keeps the Secrets in Vault of Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose". Jharkhandi Baba. 1 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- —"Listeners name 'greatest Bengali'". BBC. 14 April 2004. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

—Habib, Haroon (17 April 2004). "International : Mujib, Tagore, Bose among 'greatest Bengalis of all time'". The Hindu.

—"Bangabandhu judged greatest Bangali of all time". The Daily Star. 16 April 2004. - David L. Gosling (2007). Science and the Indian Tradition: When Einstein Met Tagore. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-134-14332-0.

- Mahanti, Subodh. "Acharya Jagadis Chandra Bose". Biographies of Scientists. Vigyan Prasar, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Mukherji, pp. 3–10.

- Murshed, Md Mahbub (2012). "Bose, Sir Jagdish Chandra". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Pursuit and Promotion of Science : The Indian Experience" (PDF). Indian National Science Academy. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- "Jagdish Chandra Bose". calcuttaweb.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- Jagadis Chandra Bose, Sir Jagadis Chunder Bose, His Life and Speeches, The Cambridge Press, Madras (Project Gutenberg eBook)

- "Bose, Jagadis Chandra (BS881JC)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Sengupta, Subodh Chandra and Bose, Anjali (editors), 1976/1998, Sansad Bangali Charitabhidhan (Biographical dictionary) Vol I, (in Bengali), p23, ISBN 81-85626-65-0

- Jagadis Chandra Bose, Sir Jagadis Chunder Bose, His Life and Speeches, The Cambridge Press, Madras (Project Gutenberg eBook)

- S. Ramaseshan, The centennial of the discovery of millimetre waves by Jagadis Chandra Bose (1858–1937), Current Science, Vol. 70, No. 2 (25 January 1996), pp. 172-175

- Geddes 1920, pp. 33–39.

- Bose, p. 7.

- "The Scientist and the Nun: How Sister Nivedita Made Sure J.C. Bose Never Gave Up" – via thewire.in.

- Mukherji, pp. 14–25

- https://vigyanprasar.gov.in/bose-jagdish-chandra/ Bose Jagdish Chandra, igyanprasar.gov.in

- Savneet kaur, Great Scientists of the World : Jagdish Chandra Bose, Diamond Pocket Books Pvt Ltd - 2022, page 45

- Subal Kar, Physics and Astrophysics - Glimpses of the Progress, CRC Press · 2022, 1.5.4 - Fallout of Maxwell and Faraday's Electromagnetism

- Geddes 1920, pp. 41–44.

- https://vigyanprasar.gov.in/bose-jagdish-chandra/ Bose Jagdish Chandra, igyanprasar.gov.in

- Bondyopadhyay, P.K. (January 1998). "Sir J. C. Bose's Diode Detector Received Marconi's First Transatlantic Wireless Signal of December 1901 (The "Italian Navy Coherer" Scandal Revisited)". Proceedings of the IEEE. 86 (1): 259–285. doi:10.1109/5.658778.

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 199

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 21

- Emerson, D. T. (1997). "The work of Jagadis Chandra Bose: 100 years of MM-wave research". IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Research. 45 (12): 2267–2273. Bibcode:1997imsd.conf..553E. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.39.8748. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602853. ISBN 978-0-9864885-1-1. S2CID 9039614. reprinted in Igor Grigorov, Ed., Antentop, Vol. 2, No.3, pp. 87–96.

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 22

- Jagadish Chandra Bose: The Real Inventor of Marconi’s Wireless Receiver; Varun Aggarwal, NSIT, Delhi, India

- The dia-heliotropic attitude of leaves as determined by transmitted nervous excitation. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspb.1922.0011

- Wildon, D. C.; Thain, J. F.; Minchin, P. E. H.; Gubb, I. R.; Reilly, A. J.; Skipper, Y. D.; Doherty, H. M.; O'Donnell, P. J.; Bowles, D. J. (1992). "Electrical signalling and systemic proteinase inhibitor induction in the wounded plant". Nature. 360 (6399): 62–5. Bibcode:1992Natur.360...62W. doi:10.1038/360062a0. S2CID 4274162.

- Response in the Living and Non-Living by Sir Jagadis Chandra Bose – Project Gutenberg. Gutenberg.org (3 August 2006). Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Jagadis Bose (2009). Response in the Living and Non-Living. Plasticine. ISBN 978-0-9802976-9-0.

- "Bengal". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- "Symposium at Christ's College to celebrate a genius". University of Cambridge. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- Jagadish Chandra Sera Rachana Sambhar, Patra Bharati, Kolkata, 1960, p 251,252

- Geddes 1920, p. 227.

- Geddess 1920, pp. 17–18.

- Acharya Bhavan Opens Its Doors to Visitors. The Times of India. 3 July 2011.

- "Collected Physical Papers". 1927.

- "J C Bose: The Scientist Who Proved That Plants Too Can Feel". Phila Mirror: The Indian Philately Journal. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "ACHARYA JAGDISH CHANDRA BOSE (LV)". Films Division.

- "Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose". Films Division. 10 September 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021.

- Jag Mohan (1990). Documentary films and Indian Awakening. Publications Division. p. 128. ISBN 978-81-230-2363-2.

- "First IEEE Milestones in India: The work of J.C. Bose and C.V. Raman to be recognized". the Institute. 7 September 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- "Jagadish Chandra Bose's 158th Birthday". 30 November 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Proud Moment For India As Scientist Sir JC Bose May Get Featured On New UK 50 Pound Note". The Times of India. 28 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "Jagadish Chandra Bose may become face of UK's new 50-pound note". dna. 26 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "Jagadish Chandra Bose among nominees to become face of UK's new 50-pound note". The Week. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "List of Past General Presidents". Indian Science Congress Association. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Grandjean, Martin (2018). Les réseaux de la coopération intellectuelle. La Société des Nations comme actrice des échanges scientifiques et culturels dans l'entre-deux-guerres [The Networks of Intellectual Cooperation. The League of Nations as an Actor of the Scientific and Cultural Exchanges in the Inter-War Period] (phdthesis) (in French). Lausanne: Université de Lausanne.

- "A new name now for grand old Indian Botanical Gardens". The Hindu. 26 June 2009. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

References

- Mukherji, Visvapriya, Jagadish Chandra Bose, second edition, 1994, Builders of Modern India series, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, ISBN 81-230-0047-2.

- Geddes, Patrick (1920). The Life and Work of Sir Jagadis C. Bose. London: Longmans.

- Bose, Jagadish Chandra. Sir Jagadis Chunder Bose His Life and Speeches.

Further reading

- Ghosh, Kunal (2022). Unsung Genius : A Life of Jagadish Chandra Bose. India. Aleph Book Company.

- Pearson G.L., Brattain W.H. (1955). "History of Semiconductor Research". Proc. IRE. 43 (12): 1794–1806. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1955.278042. S2CID 51634231.

- J.M. Payne & P.R. Jewell, "The Upgrade of the NRAO 8-beam Receiver," in Multi-feed Systems for Radio Telescopes, D.T. Emerson & J.M. Payne, Eds. San Francisco: ASP Conference Series, 1995, vol. 75, p. 144

- Fleming, J. A. (1908). The principles of electric wave telegraphy. London: New York and.

- Yogananda, Paramhansa (1946). "India's Great Scientist, J.C. Bose". Autobiography of a Yogi (1st ed.). New York: Philosophical Library. pp. 65–74.

- Bose, Jagadish Chandra: Runaway Cyclone (1921) (science fiction book translated into English)

External links

- Bose Institute website

- Jagadish Chandra Bose at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Works by or about Jagadish Chandra Bose at Internet Archive

- Works by Jagadis Chandra Bose at Project Gutenberg

- Sir Jagadis Chunder Bose by Sir Jagadis Chunder Bose at Project Gutenberg (Project Gutenberg)

- Response in the Living and Non-Living by Jagadis Chandra Bose at Project Gutenberg (Project Gutenberg)

- J. C. Bose, The Unsung hero of radio communication, web.mit.edu

- JC Bose: 60 GHz in the 1890s

- Jagadish Chandra Bose at Engineering and Technology History Wiki

- ECIT Bose article at www.infinityfoundation.com

- Jagadish Chandra Bose materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

- Entry on Bangla science fiction by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay in The Science Fiction Encyclopedia

- Newspaper clippings about Jagadish Chandra Bose in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

На других языках

[de] Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose CSI CIE FRS (Bengalisch: .mw-parser-output .Beng{font-size:110%}জগদীশ চন্দ্র বসু, Jagadīś Chandra Basu; * 30. November 1858 in Maimansingh, Bengalen, heute in Bangladesch; † 23. November 1937 in Giridih, Bengalen, heute in Indien) war ein indischer Naturwissenschaftler. Er beschäftigte sich mit Physik und Botanik und war einer der Pioniere des Radios. Neben der Schallübertragung interessierte er sich für die Auswirkungen elektromagnetischer Wellen auf Lebewesen, insbesondere auf Pflanzen, und führte hierzu eine Vielzahl von Experimenten durch. Auf Grund der Vielfältigkeit seiner Tätigkeitsfelder wurde er als Polymath bezeichnet.[1][2]- [en] Jagadish Chandra Bose

[ru] Бос, Джагдиш Чандра

Сэр Джагадиш Чандра Бос (также встречаются варианты написания фамилии — Бошу, Бозе, Боше; (англ. Jagadish Chandra Bose, бенг. জগদীশ চন্দ্র বসু Jôgodish Chôndro Boshu; 30 ноября 1858 — 23 ноября 1937) — бенгальский учёный-энциклопедист: физик, биолог, биофизик, ботаник, археолог и писатель-фантаст[5]. Он был одним из основоположников исследования радио и микроволновой оптики, внёс существенный вклад в науку о растениях, основал фонды экспериментальной науки на индийском субконтиненте[6]. Его считают одним из создателей радио[7] и отцом бенгальской научной фантастики. В 1904 году Бос первым из индусов получил патент США.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии