fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

Mortimer Jerome Adler (December 28, 1902 – June 28, 2001) was an American philosopher, educator, encyclopedist, and popular author. As a philosopher he worked within the Aristotelian and Thomistic traditions. He lived for long stretches in New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, and San Mateo, California.[1] He taught at Columbia University and the University of Chicago, served as chairman of the Encyclopædia Britannica Board of Editors, and founded his own Institute for Philosophical Research.

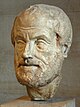

Mortimer J. Adler | |

|---|---|

Adler while presiding over the Center for the Study of The Great Ideas | |

| Born | Mortimer Jerome Adler December 28, 1902 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | June 28, 2001 (aged 98) San Mateo, California, U.S. |

| Education | Columbia University (PhD) |

| Notable work | Aristotle for Everybody, How to Read a Book, A Syntopicon |

| Spouses |

|

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

Main interests | Philosophical theology, metaphysics, ethics |

Influences | |

Influenced

| |

Biography

Intellectual development and philosophic evolution

While doing newspaper work and taking night classes during his adolescence, Adler had encountered works of men he would come to call heroes: Plato, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, John Locke, John Stuart Mill, and others, who "were assailed as irrelevant by student activists in the 1960s and subjected to 'politically correct' attack in later decades."[2] His thought evolved so as to refute "philosophical mistakes" as reflected in his 1985 book, Ten Philosophical Mistakes: Basic Errors in Modern Thought.[3] In Adler's view, these errors were introduced by Descartes on the continent and by Thomas Hobbes and David Hume in Britain, compounded and perpetuated by Kant and the idealists and existentialists on the one side, and by John Stuart Mill, Jeremy Bentham, and Bertrand Russell and the English analytic tradition on the other. Having corrected, at least to his own satisfaction, these mistakes, he gave answers to philosophic problems in the categories of thought whence they arose, finding the necessary insights and distinctions to do so by drawing from the Aristotelian tradition, as in his other written works.

New York City

Adler was born in Manhattan, New York City, on December 28, 1902, to Jewish immigrants from Germany: Clarissa (Manheim), a schoolteacher, and Ignatz Adler, a jewelry salesman.[4][5] He dropped out of school at age 14 to become a copy boy for the New York Sun, with the ultimate aspiration of becoming a journalist.[6] Adler soon returned to school to take writing classes at night, where he discovered the western philosophical tradition. After his early schooling and work, he went on to study at Columbia University and contributed to the student literary magazine, The Morningside, a poem "Choice" (in 1922 when Charles A. Wagner[7] was editor-in-chief and Whittaker Chambers an associate editor).[8] Though he refused to take the required swimming test for a bachelor's degree (a matter that was rectified when Columbia gave him an honorary degree in 1983), he stayed at the university and eventually received an instructorship and finally a doctorate in psychology.[9] While at Columbia University, Adler wrote his first book: Dialectic, published in 1927.[10]

Adler worked with Scott Buchanan at the People's Institute and then for many years on their respective Great books efforts. (Buchanan was the founder of the Great Books program at St. John's College).[11]

Chicago

In 1930, Robert Hutchins, the newly appointed president of the University of Chicago, whom Adler had befriended some years earlier, arranged for Chicago's law school to hire him as a professor of the philosophy of law. The philosophers at Chicago (who included James H. Tufts, E. A. Burtt, and George H. Mead) had "entertained grave doubts as to Dr. Adler's competence in the field [of philosophy]"[12] and resisted Adler's appointment to the university's Department of Philosophy.[13][14] Adler was the first "non-lawyer" to join the law school faculty.[15] After the Great Books seminar inspired Chicago businessman and university trustee Walter Paepcke to found the Aspen Institute, Adler taught philosophy to business executives there.[10][16]

"Great Books" and beyond

Adler and Hutchins went on to found the Great Books of the Western World program and the Great Books Foundation. In 1952, Adler founded and served as director of the Institute for Philosophical Research. He also served on the Board of Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, compiled its Syntopicon and later Propaedia, and succeeded Hutchins as its chairman from 1974. As the director of editorial planning for the fifteenth edition of Britannica from 1965, he was instrumental in the major reorganization of knowledge embodied in that edition.[17] He introduced the Paideia Proposal which resulted in his founding the Paideia Program, a grade school curriculum centered around guided reading and discussion of difficult works (as judged for each grade). With Max Weismann, he founded the Center for the Study of the Great Ideas in 1990 in Chicago.

Popular appeal

Adler long strove to bring philosophy to the masses, and some of his works (such as How to Read a Book) became popular bestsellers. He was also an advocate of economic democracy and wrote an influential preface to Louis O. Kelso's The Capitalist Manifesto.[18] Adler was often aided in his thinking and writing by Arthur Rubin, an old friend from his Columbia undergraduate days. In his own words:

Unlike many of my contemporaries, I never write books for my fellow professors to read. I have no interest in the academic audience at all. I'm interested in Joe Doakes. A general audience can read any book I write – and they do.

Dwight Macdonald once criticized Adler's popular style by saying "Mr. Adler once wrote a book called How to Read a Book. He should now read a book called How to Write a Book."[19]

Religion and theology

Adler was born into a nonobservant Jewish family. In his early twenties, he discovered St. Thomas Aquinas, and in particular the Summa Theologica.[20] Many years later, he wrote that its "intellectual austerity, integrity, precision and brilliance ... put the study of theology highest among all of my philosophical interests."[21] An enthusiastic Thomist, he was a frequent contributor to Catholic philosophical and educational journals, as well as a frequent speaker at Catholic institutions, so much so that some assumed he was a convert to Catholicism. But that was reserved for later.[20]

In 1940, James T. Farrell called Adler "the leading American fellow-traveller of the Roman Catholic Church." What was true for Adler, Farrell said, was what was "postulated in the dogma of the Roman Catholic Church," and he "sang the same tune" as avowed Catholic philosophers like Étienne Gilson, Jacques Maritain, and Martin D'Arcy. He also greatly admired Henri Bergson, the French Jewish philosopher and Nobel laureate, whose books the Catholic church had indexed as prohibited. Bergson refused to convert during the collaborationist Vichy regime, and despite the Statute on Jews he instead restated his previous views and was thus stripped of all his previous posts and honors.[20] Farrell attributed Adler's delay in joining the Church to his being among those Christians who "wanted their cake and ... wanted to eat it too" and compared him to the Emperor Constantine, who waited until he was on his deathbed to formally become a Catholic.[22]

Adler took a long time to make up his mind about theological issues. When he wrote How to Think About God: A Guide for the Twentieth-Century Pagan in 1980, he claimed to consider himself the pagan of the book's subtitle. In volume 51 of the Mars Hill Audio Journal (2001), Ken Myers includes his 1980 interview with Adler, conducted after How to Think About God was published. Myers reminisces, "During that interview, I asked him why he had never embraced the Christian faith himself. He explained that while he had been profoundly influenced by a number of Christian thinkers during his life, ... there were moral – not intellectual – obstacles to his conversion. He didn't explain any further."[23]

Myers notes that Adler finally "surrendered to the Hound of Heaven" and "made a confession of faith and was baptized" as an Episcopalian in 1984, only a few years after that interview. Offering insight into Adler's conversion, Myers quotes him from a subsequent 1990 article in Christianity magazine: "My chief reason for choosing Christianity was because the mysteries were incomprehensible. What's the point of revelation if we could figure it out ourselves? If it were wholly comprehensible, then it would just be another philosophy."[23]

According to his friend Deal Hudson, Adler "had been attracted to Catholicism for many years" and "wanted to be a Roman Catholic, but issues like abortion and the resistance of his family and friends" kept him away. Many thought he was baptized as an Episcopalian rather than a Catholic solely because of his "wonderful – and ardently Episcopal – wife" Caroline. Hudson suggests it is no coincidence that it was only after her death in 1998 that he took the final step.[24] In December 1999, in San Mateo, where he had moved to spend his last years, Adler was formally received into the Catholic Church by a long-time friend and admirer, Bishop Pierre DuMaine.[20] "Finally," wrote another friend, Ralph McInerny, "he became the Roman Catholic he had been training to be all his life".[6]

Despite not being a Catholic for most of his life, on account of his lifelong participation in the Neo-Thomist movement[23] and his almost equally long membership in the American Catholic Philosophical Association, this latter, according to McInerny[6] is willing to consider Adler "a Catholic philosopher".

Philosophy

Adler referred to Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics as the "ethics of common sense" and also as "the only moral philosophy that is sound, practical, and undogmatic."[25] Thus, it is the only ethical doctrine that answers all the questions that moral philosophy should and can attempt to answer, neither more nor less, and that has answers that are true by the standard of truth that is appropriate and applicable to normative judgments. In contrast, Adler believed that other theories or doctrines try to answer more questions than they can or fewer than they should, and their answers are mixtures of truth and error, particularly the moral philosophy of Immanuel Kant.

Adler was a self-proclaimed "moderate dualist" and viewed the positions of psychophysical dualism and materialistic monism to be opposite sides of two extremes. Regarding dualism, he dismissed the extreme form of dualism that stemmed from such philosophers as Plato (body and soul) and Descartes (mind and matter), as well as the theory of extreme monism and the mind–brain identity theory. After eliminating the extremes, Adler subscribed to a more moderate form of dualism. He believed that the brain is only a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for conceptual thought; that an "immaterial intellect" is also requisite as a condition;[26] and that the difference between human and animal behavior is a radical difference in kind. Adler defended this position against many challenges to dualistic theories.

Freedom and free will

The meanings of "freedom" and "free will" have been and are under debate, and the debate is confused because there is no generally accepted definition of either term.[27][28][29] Adler's "Institute for Philosophical Research" spent ten years studying the "idea of freedom" as the word was used by hundreds of authors who have discussed and disputed freedom.[30] The study was published in 1958 as Volume One of The Idea of Freedom, subtitled A Dialectical Examination of the Idea of Freedom with subsequent comments in Adler's Philosophical Dictionary. Adler's study concluded that a delineation of three kinds of freedom – circumstantial, natural, and acquired – is necessary for clarity on the subject.[31][32]

- "Circumstantial freedom" denotes "freedom from coercion or restraint."

- "Natural freedom" denotes "freedom of a free will" or "free choice." It is the freedom to determine one's own decisions or plans. This freedom exists in everyone inherently, regardless of circumstances or state of mind.

- "Acquired freedom" is the freedom "to will as we ought to will" and, thus, "to live as [one] ought to live." This freedom is not inherent: it must be acquired by a change whereby a person gains qualities as "good, wise, virtuous, etc."[31]

Religion

As Adler's interest in religion and theology increased, he made references to the Bible and the need to test articles of faith for compatibility with the conclusions of the science of nature and of philosophers.[33] In his 1981 book How to Think About God, Adler attempts to demonstrate God as the exnihilator (the creator of something from nothing).[2] Adler stressed that even with this conclusion, God's existence cannot be proven or demonstrated, but only established as true beyond a reasonable doubt. However, in a recent re-review of the argument, John Cramer concluded that recent developments in cosmology appear to converge with and support Adler's argument, and that in light of such theories as the multiverse, the argument is no worse for wear and may, indeed, now be judged somewhat more probable than it was originally.[34]

Adler believed that, if theology and religion are living things, there is nothing intrinsically wrong about efforts to modernize them. They must be open to change and growth like everything else. Furthermore, there is no reason to be surprised when discussions such as those about the "death of God" – a concept drawn from Friedrich Nietzsche – stir popular excitement as they did in the recent past and could do so again today. According to Adler, of all the great ideas, the idea of God has always been and continues to be the one that evokes the greatest concern among the widest group of men and women. However, he was opposed to the idea of converting atheism into a new form of religion or theology.

Personal life

Mortimer Adler was married twice and had four children.[35] He and Helen Boynton, with whom in 1938 and 1940, respectively, he adopted two children, Mark and Michael, were married in 1927 and later divorced in 1960. In 1963, Adler married Caroline Pring, his junior by thirty-four years; they had two children, Douglas and Philip.[36][37][38][39]

Awards

Published works

- Dialectic (1927)

- The Nature of Judicial Proof: An Inquiry into the Logical, Legal, and Empirical Aspects of the Law of Evidence (1931, with Jerome Michael)

- Diagrammatics (1932, with Maude Phelps Hutchins)

- Crime, Law and Social Science (1933, with Jerome Michael)

- Art and Prudence: A Study in Practical Philosophy (1937)

- What Man Has Made of Man: A Study of the Consequences of Platonism and Positivism in Psychology (1937)[42]

- St. Thomas and the Gentiles (1938)

- The Philosophy and Science of Man: A Collection of Texts as a Foundation for Ethics and Politics (1940)

- How to Read a Book: The Art of Getting a Liberal Education (1940), 1966 edition subtitled A Guide to Reading the Great Books, 1972 revised edition with Charles Van Doren, The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading: ISBN 0-671-21209-5

- A Dialectic of Morals: Towards the Foundations of Political Philosophy (1941)

- "How to Mark a Book". The Saturday Review of Literature. July 6, 1940.[43]

- How to Think About War and Peace (1944)

- The Revolution in Education (1944, with Milton Mayer)

- Adler, Mortimer J. (1947). Heywood, Robert B. (ed.). The Works of the Mind: The Philosopher. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 752682744.

- The Idea of Freedom: A Dialectical Examination of the Idea of Freedom, vol. 1, Doubleday, 1958.

- The Capitalist Manifesto (1958, with Louis O. Kelso) ISBN 0-8371-8210-7

- The New Capitalists: A Proposal to Free Economic Growth from the Slavery of Savings (1961, with Louis O. Kelso)

- The Idea of Freedom: A Dialectical Examination of the Controversies about Freedom (1961)

- Great Ideas from the Great Books (1961)

- The Conditions of Philosophy: Its Checkered Past, Its Present Disorder, and Its Future Promise (1965)

- The Difference of Man and the Difference It Makes (1967)

- The Time of Our Lives: The Ethics of Common Sense (1970)

- The Common Sense of Politics (1971)

- The American Testament (1975, with William Gorman)

- Some Questions About Language: A Theory of Human Discourse and Its Objects (1976)

- Philosopher at Large: An Intellectual Autobiography (1977)

- Reforming Education: The Schooling of a People and Their Education Beyond Schooling (1977, edited by Geraldine Van Doren)

- Aristotle for Everybody: Difficult Thought Made Easy (1978) ISBN 0-684-83823-0

- How to Think About God: A Guide for the 20th-Century Pagan (1980) ISBN 0-02-016022-4

- Six Great Ideas: Truth–Goodness–Beauty–Liberty–Equality–Justice (1981) ISBN 0-02-072020-3

- The Angels and Us (1982)

- The Paideia Proposal: An Educational Manifesto (1982) ISBN 0-684-84188-6

- How to Speak / How to Listen (1983) ISBN 0-02-500570-7

- Paideia Problems and Possibilities: A Consideration of Questions Raised by The Paideia Proposal (1983)

- A Vision of the Future: Twelve Ideas for a Better Life and a Better Society (1984) ISBN 0-02-500280-5

- The Paideia Program: An Educational Syllabus (1984, with Members of the Paideia Group) ISBN 0-02-013040-6

- Ten Philosophical Mistakes: Basic Errors In Modern Thought – How they came about, their consequences, and how to avoid them. (1985) ISBN 0-02-500330-5

- A Guidebook to Learning: For a Lifelong Pursuit of Wisdom (1986)

- We Hold These Truths: Understanding the Ideas and Ideals of the Constitution (1987). ISBN 0-02-500370-4

- Reforming Education: The Opening of the American Mind (1988, edited by Geraldine Van Doren)

- Intellect: Mind Over Matter (1990)

- Truth in Religion: The Plurality of Religions and the Unity of Truth (1990) ISBN 0-02-064140-0

- Haves Without Have-Nots: Essays for the 21st Century on Democracy and Socialism (1991) ISBN 0-02-500561-8

- Desires, Right & Wrong: The Ethics of Enough (1991)

- A Second Look in the Rearview Mirror: Further Autobiographical Reflections of a Philosopher At Large (1992)

- The Great Ideas: A Lexicon of Western Thought (1992)

- Natural Theology, Chance, and God (The Great Ideas Today, 1992)

- Adler, Mortimer J. (1993). The Four Dimensions of Philosophy: Metaphysical, Moral, Objective, Categorical. Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-500574-X.

- Art, the Arts, and the Great Ideas (1994)

- Philosophical Dictionary: 125 Key Terms for the Philosopher's Lexicon, Touchstone, 1995.

- How to Think About The Great Ideas (2000) ISBN 0-8126-9412-0

- How to Prove There is a God (2011) ISBN 978-0-8126-9689-9

Anthologies, collections and surveys edited by Adler

- Scholasticism and Politics (1940)

- Great Books of the Western World (1952, 52 volumes), 2nd edition 1990, 60 volumes

- A Syntopicon: An Index to The Great Ideas (1952, 2 volumes), 2nd edition 1990

- The Great Ideas Today (1961–77, 17 volumes), with Robert Hutchins, 1978–99, 21 volumes

- The Negro in American History (1969, 3 volumes), with Charles Van Doren

- Gateway to the Great Books (1963, 10 volumes), with Robert Hutchins

- The Annals of America (1968, 21 volumes)

- Propædia: Outline of Knowledge and Guide to The New Encyclopædia Britannica 15th Edition (1974, 30 volumes)

- Great Treasury of Western Thought (1977, with Charles Van Doren) ISBN 0412449900

See also

- List of American philosophers

- Educational perennialism

References

- "Adler", The great ideas (short biography), archived from the original on December 10, 2014, retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Mortimer Adler: 1902–2001 – The Day Philosophy Died, Word gems, archived from the original on April 10, 2011

- Ten Philosophical Mistakes: Basic Errors in Modern Thought – How They Came About, Their Consequences, and How to Avoid Them, Macmillan (1985). ISBN 9780025003309

- Diane Ravitch, Left Back: A Century of Battles Over School Reform, Simon and Schuster (2001), p. 298

- "Mortimer J. Adler | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com.

- McInerny, Ralph, Memento Mortimer, Radical academy, archived from the original on November 27, 2010.

- "Charles A. Wagner", The New York Times (obituary), December 10, 1986.

- The Morningside. Vol. x. Columbia University Press. April–May 1922. p. 113. ISBN 0-300-08462-5.

- "Mortimer J Adler", Remarkable Columbians, Columbia U.

- "Mortimer Adler", Faculty, Selu

- Adler, Mortimer J. (1977). Philosopher at Large: An Intellectual Autobiography. Macmillan. p. 58–59 (St. John's College), 87–88 (People's Institute), 92–93 (rift), 113–116 (1929 collaboration). Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- A Statement from the Department of Philosophy, Chicago, quoted on Cook, Gary (1993), George Herbert Mead: The Making of a Social Pragmatist, U. of Illinois Press, p. 186.

- Van Doren, Charles (November 2002), "Mortimer J. Adler (1902–2001)", Columbia Forum (online ed.), archived from the original on June 9, 2007.

- Temes, Peter (July 3, 2001), "Death of a Great Reader and Philosopher", Sun-Times, Chicago, archived from the original on November 4, 2007.

- Centennial Facts of the Day (website), U Chicago Law School, archived from the original on October 26, 2004.

- "A Brief History of the Aspen Institute". The Aspen Institute. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- Adler, Mortimer J (1986), A Guidebook to Learning: For the Lifelong Pursuit of Wisdom, New York: Macmillan, p. 88.

- Kelso, Louis O; Adler, Mortimer J (1958), The Capitalist Manifesto (PDF), Kelso institute.

- Rosenberg, Bernard. "Assaulting the American Mind." Dissent. Spring 1988.

- Redpath, Peter, A Tribute to Mortimer J. Adler, Salvation is from the Jews.

- Adler, Mortimer J (1992), A Second Look in the Rearview Mirror: Further Autobiographical Reflections of a Philosopher at Large, New York: Macmillan, p. 264.

- Farrell, James T (1945) [1940], "Mortimer T. Adler: A Provincial Torquemada", The League of Frightened Philistines and Other Papers (reprint), New York: Vanguard Press, pp. 106–109.

- Mortimer Adler (biography), Basic Famous People.

- Hudson, Deal (June 29, 2009), "The Great Philosopher Who Became Catholic", Inside catholic, archived from the original on April 10, 2011, retrieved October 18, 2010.

- Adler, Mortimer Ten Philosophical Mistakes: Basic Errors in Modern Thought: How They Came About, Their Consequences, and How to Avoid Them.(1985) ISBN 0-02-500330-5, p. 196

- Mortimer J. Adler on the Immaterial Intellect, Book of Job, archived from the original on September 22, 2004.

- Kane, Robert (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Free Will, p. 10.

- Fischer, John Martin; Kane, Robert; Pereboom, Derk; Vargas, Manuel (2007), Four Views on Free Will, Blackwell, p. 128

- Barnes, R Eric, Freedom, Mtholyoke, archived from the original on February 16, 2005, retrieved October 19, 2009.

- Adler 1995, p. 137, Liberty.

- Adler 1958, pp. 127, 135, 149.

- Adler 1995, pp. 137–138, Liberty.

- Adler, Mortimer J (1992) [Macmillan, 1990], 'Truth in Religion: The Plurality of Religions and the Unity of Truth (reprint), Touchstone, pp. 29–30.

- John Cramer. "Adler's Cosmological Argument for the Existence of God". Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, March 1995, pp. 32–42.

- Grimes, William (June 29, 2001), "Mortimer Adler, 98, Dies; Helped Create Study of Classics", The New York Times.

- Tribune, Chicago. "Caroline Pring Adler". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- "Mortimer Adler Dies". Washington Post. June 30, 2001. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- Adler, Mortimer (1977). Philosopher at Large: An Intellectual Autobiography. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. pp. 96. ISBN 0-02-500490-5.

- Adler, Philosopher at Large: An Intellectual Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1977), p. 227.

- "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- "Aspen Hall of Fame Inductees". Aspen Hall of Fame.

- What Man Has Made of Man, Archive, 1938, OCLC 807118494.

- Mortimer J. Adler (July 6, 1940), "How to Mark a Book", The Saturday Review of Literature: 11–12

Further reading

- Ashmore, Harry (1989). Unseasonable Truths: The Life of Robert Maynard Hutchins. New York: Little Brown. ISBN 9780316053969.

- Beam, Alex (2008). A Great Idea at the Time: The Rise, Fall, and Curious Afterlife of the Great Books. New York: Public Affairs.

- Crockett, Jr.; Bennie R. (2000). Mortimer J. Adler: An Analysis and Critique of His Eclectic Epistemology (Ph.D. dissertation). University of Wales, Lampeter, UK.

- Dzuback, Mary Ann (1991). Robert M. Hutchins: Portrait of an Educator. Chicago: University of Chicago. ISBN 9780226177106.

- Kass, Amy A. (1973). Radical Conservatives for a Liberal Education. PhD dissertation.

- Lacy, Tim Lacy (2006). Making a Democratic Culture: The Great Books Idea, Mortimer J. Adler, and Twentieth-Century America (Ph.D. dissertation). Chicago: Loyola University.

- McNeill, William (1991). Hutchins' University: A Memoir of the University of Chicago 1929–50. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Moorhead, Hugh Moorhead (1964). The Great Books Movement(Ph.D. dissertation). University of Chicago. OCLC 6060691.

- Rubin, Joan Shelley (1992). The Making of Middlebrow Culture (Ph.D. dissertation). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

External links

- Center for the Study of The Great Ideas

- Mortimer J. Adler at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Adler papers at University of Texas at Austin

- Adler papers at Syracuse University

- Guide to the Mortimer J. Adler Papers 1914–1995 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии