fiction.wikisort.org - Actor

Shintaro Ishihara (石原 慎太郎, Ishihara Shintarō, 30 September 1932 – 1 February 2022) was a Japanese politician and writer who was Governor of Tokyo from 1999 to 2012. Being the former leader of the radical right Japan Restoration Party,[1] he was one of the most prominent ultranationalists in modern Japanese politics.[2][3] An ultranationalist, he was infamous for his misogynistic comments, racist remarks, xenophobic views and hatred of Chinese and Koreans, including using the antiquated pejorative term "sangokujin".[4][5][6]

Shintarō Ishihara | |

|---|---|

石原 慎太郎 | |

Ishihara in 2009 at governor's office | |

| Governor of Tokyo | |

| In office 23 April 1999 – 31 October 2012 | |

| Preceded by | Yukio Aoshima |

| Succeeded by | Naoki Inose |

| Minister of Transport | |

| In office 6 November 1987 – 27 November 1988 | |

| Prime Minister | Noboru Takeshita |

| Preceded by | Ryūtarō Hashimoto |

| Succeeded by | Shinji Satō |

| Director General of the Environment Agency | |

| In office 24 December 1976 – 28 November 1977 | |

| Prime Minister | Takeo Fukuda |

| Preceded by | Shigesada Marumo |

| Succeeded by | Hisanari Yamada |

| Member of the House of Councillors for National Block | |

| In office 8 July 1968 – 25 November 1972 | |

| Member of the House of Representatives for Tokyo 2nd district | |

| In office 10 December 1972 – 18 March 1975 | |

| In office 10 December 1976 – 14 April 1995 | |

| Member of the House of Representatives for Tokyo PR Block | |

| In office 11 December 2012 – 21 November 2014 | |

| Preceded by | Ichirō Kamoshita |

| Succeeded by | Akihisa Nagashima |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 September 1932 Suma-ku, Kobe, Japan |

| Died | 1 February 2022 (aged 89) Ōta, Tokyo, Japan |

| Cause of death | Pancreatic cancer |

| Political party | Liberal Democratic (1968–1973, 1976–1995) Independent (1973–1976, 1995–2012) Sunrise (2012) Japan Restoration (2012–2014) Future Generations (2014–2015) |

| Spouse | Noriko Ishihara |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | Hitotsubashi University |

| Profession | Novelist, author |

Also a critic of relations between Japan and the United States, his arts career included a prize-winning novel, best-sellers, and work also in theater, film, and journalism. His 1989 book, The Japan That Can Say No, co-authored with Sony chairman Akio Morita (released in 1991 in English), called on the authors' countrymen to stand up to the United States.

After an early career as a writer and film director, Ishihara served in the House of Councillors from 1968 to 1972, in the House of Representatives from 1972 to 1995, and as Governor of Tokyo from 1999 to 2012. He resigned from the governorship to briefly co-lead the Sunrise Party, then joined the Japan Restoration Party and returned to the House of Representatives in the 2012 general election.[7] He unsuccessfully sought re-election in the general election of November 2014, and officially left politics the following month.[8]

Early life and artistic career

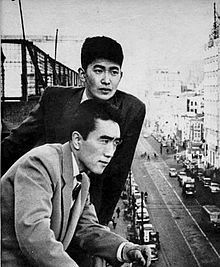

Shintaro Ishihara was born in Suma-ku, Kobe. His father Kiyoshi was an employee, later a general manager, of a shipping company. Shintaro grew up in Zushi, Kanagawa. In 1952, he entered Hitotsubashi University, and he graduated in 1956. Just two months before graduation, Ishihara won the Akutagawa Prize (Japan's most prestigious literary prize) for the novel Season of the Sun.[9][10] His brother Yujiro played a supporting role in the movie adaptation of the novel (for which Shintaro wrote the screenplay).[11] Ishihara had dabbled in directing a couple of films starring his brother. Regarding these early years as a filmmaker, he said to a Playboy Magazine interviewer in 1990 that "If I had remained a movie director, I can assure you that I would have at least become a better one than Akira Kurosawa".[12][13]

In the early 1960s, he concentrated on writing, including plays, novels, and a musical version of Treasure Island. One of his later novels, Lost Country (1982), speculated about Japan under the control of the Soviet Union.[14] He also ran a theatre company, and found time to visit the North Pole, race his yacht The Contessa and cross South America on a motorcycle. He wrote a memoir of his journey, Nanbei Odan Ichiman Kiro.[15]

From 1966 to 1967, he covered the Vietnam War at the request of Yomiuri Shimbun, and the experience influenced his decision to enter politics.[16] He also was mentored by the influential author and political "fixer" Tsûsai Sugawara.[17]

Political career

In 1968, Ishihara ran as a candidate on the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) national slate for the House of Councillors. He placed first on the LDP list with an unprecedented 3 million votes.[18] After four years in the upper house, Ishihara ran for the House of Representatives representing the second district of Tokyo, and again won election.[citation needed]

In 1973, he joined with thirty other LDP lawmakers in the anti-communist Seirankai or "Blue Storm Group"; the group gained notoriety for sealing a pledge of unity in their own blood.[11]

Ishihara ran for Governor of Tokyo in 1975 but lost to the popular Socialist incumbent Ryokichi Minobe. Minobe was 71 at the time, and Ishihara criticized him as being "too old".[19]

Ishihara returned to the House of Representatives afterward, and worked his way up the party's internal ladder, serving as Director-General of the Environment Agency under Takeo Fukuda (1976) and Minister of Transport under Noboru Takeshita (1989). During the 1980s, Ishihara was a highly visible and popular LDP figure, but was unable to win enough internal support to form a true faction and move up the national political ladder.[20] In 1983 his campaign manager put up stickers throughout Tokyo stating that Ishihara's political opponent was an immigrant from North Korea. Ishihara denied that this was discrimination, saying that the public had a right to know.[21]

In 1989, shortly after losing a highly contested race for the party presidency, Ishihara came to the attention of the West through his book The Japan That Can Say No, co-authored with Sony chairman Akio Morita. The book called on his fellow countrymen to stand up to the United States.[22]

Governor of Tokyo

In the 1999 Tokyo gubernatorial election, he ran on an independent platform and was elected as Governor of Tokyo. Among Ishihara's moves as governor, he:

- Cut metropolitan spending projects, including plans for a new Toei Subway line, and proposed the sale or leasing out of many metropolitan facilities.[14]

- Imposed a new tax on banks' gross profits (rather than net profits).[23]

- Imposed a new hotel tax based on occupancy.[24]

- Imposed restrictions on the operation of diesel-powered vehicles, following a highly publicized event where he held up a bottle of diesel soot before cameras and reporters.[25]

- Imposed cap and trade energy tax.[26]

- Proposed opening casinos in the Odaiba district.[14]

- Declared in 2005 that Tokyo would bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics, which discouraged a bid by Fukuoka.[27] Tokyo's bid lost to that of Rio de Janeiro.

- Set up the ShinGinko Tokyo bank to lend to SMEs (small medium enterprises) in Tokyo. This bank has lost approximately 1 billion dollars worth of taxpayers' money through inadequate customer risk assessments.[28]

- Served as Chairman of Tokyo's successful bid to host the 2020 Summer Olympics.[29]

- Generated controversy from PETA for the culling of the 37,000 crows that populated Tokyo.[30]

He won re-election in 2003 with 70.2% of the vote,[citation needed] and re-election in 2007 with 50.52% of the vote.[citation needed] In the 2011 gubernatorial election, his share of the vote dipped to 43.4% against challenges by comedian Hideo Higashikokubaru and entrepreneur Miki Watanabe.[citation needed]

On 25 October 2012, Ishihara announced he would resign as Governor of Tokyo to form a new political party in preparation for upcoming national elections.[31] Following his announcement, the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly approved his resignation on 31 October 2012, officially ending his tenure as Governor of Tokyo for 4,941 days, the second-longest term after Shunichi Suzuki.[citation needed]

Sunrise Party

Ishihara's new national party was expected to be formed with members of the right-wing Sunrise Party of Japan, which he had helped to set up in 2010.[19] When announced by co-leaders Ishihara and SPJ chief Takeo Hiranuma on 13 November 2012, Sunrise Party incorporated all five members of SPJ. SP would look to form a coalition with other small parties including Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto's Japan Restoration Party (Nippon Ishin no Kai).[32]

In November 2012, Ishihara and his co-leader Hiranuma said that the Sunrise Party would pursue "establishment of an independent Constitution, beefing up of Japan's defense capabilities, and fundamental reform of fiscal management and tax systems to make them more transparent". The future of nuclear power and the upcoming consumption tax hike were issues it would have to address with potential coalition partners.[32]

Sunrise Party merger with the Japan Restoration Party

Only four days after the Sunrise Party was launched, on 17 November 2012, Ishihara and Tōru Hashimoto, leader of the Japan Restoration Party (JRP), decided to merge their parties, with Ishihara becoming the head of the JRP. Your Party would not join the party, nor would Genzei Nippon, as the latter party's anti-consumption tax increase policy did not match the JRP's pro-consumption tax policy.[33]

Reporting on a poll in early December 2012, Asahi Shimbun characterized the merger with Japan Restoration Party as the latter having "swallowed up" Sunrise. The poll, in advance of the 16 December Lower House elections, also said the association with SP could hurt JRP's chances of forming a ruling coalition even though JRP was showing strength relative to the ruling DPJ.[34]

Party for Future Generations

In the December 2014 general elections he was a candidate for the Party for Future Generations, an extreme right-wing party, but was defeated.[4] Following this, he retired from politics.[citation needed]

Political views

Ishihara is generally described as having been one of Japan's most prominent extreme right-wing politicians.[35][36][37] He was called "Japan's Le Pen" on a program broadcast on Australia's ABC.[38] He was affiliated with the openly ultranationalist organization Nippon Kaigi.[39]

Foreign relations

Ishihara was a long-term friend of the prominent Aquino family in the Philippines. He is credited with being been the first person to inform future President Corazon Aquino about the assassination of her husband Senator Benigno Aquino Jr. on 21 August 1983.[40]

Ishihara was often been critical of Japan's foreign policy as being non-assertive. Regarding Japan's relationship with the U.S., he stated that "The country I dislike most in terms of U.S.–Japan ties is Japan, because it's a country that can't assert itself."[20] As part of the criticism, Ishihara published a book co-authored with the then Prime minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad, titled "No" to ieru Ajia – tai Oubei e no hōsaku in 1994.[41]

Ishihara was also long critical of the government of the People's Republic of China. He invited the Dalai Lama and the President of the Republic of China Lee Teng-hui to Tokyo.[14]

Ishihara was deeply interested in the North Korean abduction issue, and called for economic sanctions against North Korea.[42] Following Ishihara's campaign to bid Tokyo for the 2016 Summer Olympics, he eased his criticism of the PRC government. He accepted an invitation to attend the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, and was selected as a torch-bearer for the Japan leg of the 2008 Olympic Torch Relay.[43]

Views on foreigners in Japan

On 9 April 2000, in a speech before a Self-Defense Forces group, Ishihara said crimes were repeatedly committed by illegally entered people, using the pejorative term sangokujin, and foreigners. He also speculated that in the event a natural disaster struck the Tokyo area, they would be likely to cause civil disorder.[44][45] His comment invoked calls for his resignation, demands for an apology and fears among residents of Korean descent in Japan,[14] as well as being criticised by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.[46][47]

Regarding this statement, Ishihara later said:

I referred to the "many sangokujin who entered Japan illegally." I thought some people would not know that word so I paraphrased it and used gaikokujin, or foreigners. But it was a newspaper holiday so the news agencies consciously picked up the sangokujin part, causing the problem.

... After World War II, when Japan lost, the Chinese of Taiwanese origin and people from the Korean Peninsula persecuted, robbed and sometimes beat up Japanese. It's at that time the word was used, so it was not derogatory. Rather we were afraid of them.

... There's no need for an apology. I was surprised that there was a big reaction to my speech. In order not to cause any misunderstanding, I decided I will no longer use that word. It is regrettable that the word was interpreted in the way it was.[20]

On 20 February 2006, Ishihara also said: "Roppongi is now virtually a foreign neighborhood. Africans—I don't mean African-Americans—who don't speak English are there doing who knows what. This is leading to new forms of crime such as car theft. We should be letting in people who are intelligent."[48]

On 17 April 2010, Ishihara said "many veteran lawmakers in the ruling-coalition parties are naturalized or the offspring of people naturalized in Japan".[49]

Other controversial statements

In 1990, Ishihara said in a Playboy interview that the Rape of Nanking was a fiction, claiming, "People say that the Japanese made a holocaust but that is not true. It is a story made up by the Chinese. It has tarnished the image of Japan, but it is a lie."[50][51] He continued to defend this statement in the uproar that ensued.[52] He also backed the film The Truth about Nanjing, a Japanese film that denies the atrocity.[53]

In 2000, Ishihara, one of the eight judges for a literary prize, commented that homosexuality is abnormal, which caused an outrage in the gay community in Japan.[54]

In a 2001 interview with women's magazine Shukan Josei, Ishihara said that he believed "old women who live after they have lost their reproductive function are useless and are committing a sin," adding that he "couldn't say this as a politician." He was criticized in the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly for these comments, but responded that the criticism was driven by "tyrant… old women."[55]

During an inauguration of a university building in 2004, Ishihara stated that French is unqualified as an international language because it is "a language in which nobody can count", referring to the counting system in French, which is based on units of twenty for numbers from 70 to 99 rather than ten (as is the case in Japanese and English). The statement led to a lawsuit from several language schools in 2005. Ishihara subsequently responded to comments that he did not disrespect French culture by professing his love of French literature on Japanese TV news.[56]

At a Tokyo IOC press briefing in 2009, Governor Ishihara dismissed a letter sent by environmentalist Paul Coleman regarding the contradiction of his promoting the Tokyo Olympic 2016 bid as 'the greenest ever' while destroying the forested mountain of Minamiyama, the closest 'Satoyama' to the centre of Tokyo, by angrily stating Coleman was 'Just a foreigner, it does not matter'. Then, on continued questioning by investigative journalist Hajime Yokota, he stated 'Minamiyama is a Devil's Mountain that eats children.' Then he went on to explain how unmanaged forests 'eat children' and implied that Yokota, a Japanese national, was betraying his nation by saying 'What nationality are you anyway?' This was recorded on film[57] and turned into a video that was sent around the world as the Save Minamiyama Movement[58]

In 2010, Ishihara claimed that Korea under Japanese rule was absolutely justified due to historical pressures from Qing dynasty and Imperial Russia.[59]

In reference to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Ishihara said "that the disaster was 'punishment from heaven' because Japanese have become greedy".[60][61][62]

America's identity is freedom. France's identity is freedom, equality and fraternity. Japan has no sense of that. Only greed. Material greed, monetary greed.[63]

This greed bounds with populism. These things need to be washed away with the Tsunami. For many years the heart of Japanese always bounded with devil.[64]

Japanese's identity is greed. We should avail of this tsunami to wash away this greed. I think this is a divine punishment.[65]

— Ishihara Shintaro

However, he also commented that the victims of this disaster were pitiable.[66]

This speech quickly caused many controversies and critical responses from the public opinion, both inside and outside Japan. The governor of Miyagi expressed displeasure about Ishihara's speech, claimed that Ishihara should have considered the victims of the disaster. Ishihara then had to apologize for his comments.[67]

During the 2012 Summer Olympics, Ishihara stated that "Westerners practicing judo resembles beasts fighting. Internationalized judo has lost its appeal." He added, "In Brazil they put chocolate in norimaki, but I wouldn't call it sushi. Judo has gone the same way."[68]

Ishihara has said that Japan ought to have nuclear weapons.[69]

Proposal to buy the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands

On 15 April 2012, Ishihara made a speech in Washington, D.C., publicly stating his desire for Tokyo to purchase the Senkaku Islands, called the Diaoyu Islands by mainland China, on behalf of Japan in an attempt to end the territorial dispute between China and Japan, causing uproars in Chinese society and increasing tension between the governments of China and Japan.[70][71]

Personal life and death

Ishihara was married to Noriko Ishihara and had four sons. Members of the House of Representatives Nobuteru Ishihara and Hirotaka Ishihara are his eldest and third sons; actor and weatherman Yoshizumi Ishihara is his second son. His youngest son, Nobuhiro Ishihara, is a painter.[72] The late actor Yujiro Ishihara was his younger brother.[citation needed]

He died from pancreatic cancer at his home in Ōta, Tokyo[citation needed] on 1 February 2022, at the age of 89.[73][74][75]

Books written by Ishihara

This section does not cite any sources. (February 2022) |

- Taiyō no kisetsu (太陽の季節), Season of the Sun, 1956: Akutagawa Prize, The Best New Author of the Year Prize.

- Kurutta kajitsu (狂った果実), Crazed Fruit, 1956.

- Kanzen Na Yuugi (完全な遊戯), The Perfect Game, 1956.

- Umi no chizu (海の地図), Map of the sea, 1958.

- Seinen no ki (青年の樹), Tree of the youth.

- Gesshoku (月蝕), Lunar eclipse, 1959.

- Nanbei ōdan ichi man kiro (南米横断1万キロ), 10 thousand kilometers motoring across South America

- Seishun to wa nanda (青春とはなんだ), What does youth mean? .

- Ōinaru umi e (大いなる海へ), To the great sea, 1965.

- Kaeranu umi (還らぬ海), Unretreating Sea 1966.

- Suparuta kyōiku (スパルタ教育) Spartan education 1969.

- Kaseki no mori(化石の森), Petrified forest, 1970: Minister of Education Prize

- Shintarō no seiji chousho (慎太郎の政治調書), Shintaro's political record 1970.

- Shintarō no daini seiji chousho (慎太郎の第二政治調書), Shintaro's second political record 1971.

- Shin Wakan rōeishū (新和漢朗詠集), New Wakan rōeishū (collection of Japanese and Chinese poems) 1973.

- Yabanjin no daigaku (野蛮人の大学), University of barbarians .

- Boukoku -Nihon no totsuzenshi (亡国 -日本の突然死), The ruin of a nation -Japan's sudden death 1982.

- 'Nō' to ieru Nihon (「NO」と言える日本), The Japan That Can Say No (in collaboration with Akio Morita), 1989.

- Soredemo 'Nō' to ieru Nihon. Nichibeikan no konponmondai (それでも「NO」と言える日本 ―日米間の根本問題―) The Japan That Still Can Say No. Principal problem of the Japan–US relations (in collaboration with Shōichi Watanabe and Kazuhisa Ogawa), 1990.

- Waga jinsei no toki no toki (わが人生の時の時), The sublime moment of my life, 1990.

- Danko 'No' to ieru Nihon (断固「NO」と言える日本) The Japan That Can Strongly Say No (in collaboration with Jun Etō) 1991.

- Mishima Yukio no nisshoku (三島由紀夫の日蝕), The eclipse of Yukio Mishima 1991.

- 'No' to ieru Asia (「NO」と言えるアジア), The Asia That Can Say NO (in collaboration with Mahathir Mohamad)

- Kaze ni tsuite no kioku (風についての記憶), My memory about the wind, 1994.

- Otōto (弟), Younger brother, 1996 : Mainichibungakusho Special Prize.

- 'Chichi' nakushite kuni tatazu ("父"なくして国立たず), No country can stand without "father", 1997.

- Sensen fukoku 'Nō' to ieru Nihon keizai -Amerika no kin'yū dorei kara no kaihō- (宣戦布告「NO」と言える日本経済 ―アメリカの金融奴隷からの解放―), Declaration of War, Economy of Japan That Can Say No -Liberation from America's financial slavery, 1998.

- Hokekyō o ikiru (法華経を生きる), To live the Lotus Sutra, 1998.

- Seisan (聖餐), Eucharist, 1999.

- Kokka naru gen'ei (国家なる幻影), An illusion called nation, 1999.

- Amerika shinkō wo suteyo 2001 nen kara no nihon senryaku (「アメリカ信仰」を捨てよ ―2001年からの日本戦略), Stop worshipping America -Japan strategy from 2001, 2000.

- Boku wa kekkon shinai (僕は結婚しない) I won't marry, 2001.

- Ima 'Tamashii' no kyōiku (いま「魂」の教育), Now, 'spirit' education, 2001.

- Ei'en nare, nihon -moto sōri to tochiji no katariai (永遠なれ、日本 -元総理と都知事の語り合い), Japan Forever – A talk between ex-premier and Tokyo governor (in collaboration with Yasuhiro Nakasone), 2001.

- Oite koso jinsei (老いてこそ人生), To get old is the life, 2002.

- Hi no shima (火の島), Island of fire, 2008.

- Watashi no suki na nihonjin (私の好きな日本人), My favorite Japanese persons, 2008.

- Saisei (再生), Recovery, 2010.

- Shin Darakuron -Gayoku to tenbatsu (新・堕落論-我欲と天罰), New "On Decadance" -Greed and divine punishment ,2011

Translation work

- Robert Ringer: Winning Through Intimidation 1978.

Translations in English

- The Japan That Can Say No (in collaboration with Akio Morita), Simon & Schuster, 1991, ISBN 0-671-72686-2. Touchstone Books, 1992, ISBN 0-671-75853-5. Cassette version ISBN 0-671-73571-3. Disk version, 1993, ISBN 1-882690-23-0.

Film career

He acted in six films, including Crazed Fruit (1956) and The Hole (1957), and co-directed the 1962 film Love at Twenty (with François Truffaut, Marcel Ophüls, Renzo Rossellini and Andrzej Wajda).[76]

Honours

- Akutagawa Prize (1956)[citation needed]

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (2015)[citation needed]

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (2015)[citation needed]

See also

- Ethnic issues in Japan

References

- Rydgren, Jens (2018). The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Oxford University Press. pp. 772–773. ISBN 978-0190274559. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Michiyo Nakamoto; Mure Dickie (21 March 2012). "China protests spur Japanese nationalists". Financial Times. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- The Associated Press (17 November 2012). "Ex-Tokyo governor, mayor form own party for national election". CTV News. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- Mizuho Aoki (16 December 2014). "Controversial to the end, Shintaro Ishihara bows out of politics". The Japan Times. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- Kyodo (10 March 2001). "Ishihara slammed for racist remarks". The Japan Times. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- "Shintaro Ishihara: A politician who peddled hatred". 4 February 2022.

- "Ex-Tokyo Gov. Ishihara set to secure lower house seat". Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Japan Times. 16 December 2012 - 引退会見詳報 [Full Report of Retirement Press Conference] (in Japanese). 16 December 2014. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- "太陽の季節:ここに始まる-炎のランナー". I-shintaro.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- "Profile of the Governor, Tokyo Metropolitan Government". Metro.tokyo.jp. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- "Mayors: Shintaro Ishihara: Governor of Tokyo". Citymayors.com. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- Playboy, Vol. 37, No. 10, p. 76.

- Stonefish, Isaac (1 November 2013) The Man Who Would Be Warlord. Foreign Policy.

- Larimer, Tim (24 April 2000) "Rabble Rouser" Archived 8 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, TIME Asia.

- "Profile of Shintaro Ishihara". Ezipangu.org. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- "Sensen Fukoku". Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), accessed 22 December 2010. (in Japanese) - Wani, Yukio (8 July 2012). "Barren Senkaku Nationalism and China-Japan Conflict". The Asia-Pacific Journal. apjjf.org. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Emmerson, John J., Arms, Yen & Power: The Japanese Dilemma, (Tokyo: C.E. Tuttle, 1971), p. 339.

- Nagata, Kazuaki, "Ishihara leaves office with sights on Diet seat", The Japan Times, 1 November 2012.

- "'There's No Need For an Apology': Tokyo's boisterous governor is back in the headlines Archived April 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine," TIME Asia, 24 April 2000.

- 河信基 『代議士の自決ー新井将敬の真実』(河信基・三一書房)

- Kwai, Isabella; Inoue, Makiko (2 February 2022). "Shintaro Ishihara, Outspoken Nationalist Governor of Tokyo, Dies at 89". New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- DeWit, Andrew, and Masaru Kaneko, "Ishihara and the Politics of His Bank Tax", JPRI Critique 9:4, May 2002.

- "Tokyo hotel tax plan enacted," Kyodo News International, 24 December 2001.

- "Diesels may return to Japan roads". Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Reuters, 3 March 2006. - Carbon Trades of Up to $212 Billion Opposed by Japan, South Korea Firms, Bloomberg, 13 January 2011.

- "Tokyo governor suggests bid for 2016 Olympics Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine," Daily Times, 6 August 2005.

- "ShinGinko Tokyo: the crumbling icon of imbecility". Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Times Online, 13 August 2007. - "Japanese Olympic Committee To Appoint Chairman For Tokyo 2020 Bid". GamesBids.com. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- "Policy Speech by Governor of Tokyo, Shintaro Ishihara". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), First Regular Session of the Metropolitan Assembly, 2002. metro.tokyo.jp - "Ishihara resigns as Tokyo governor to launch new political party". Japan Today. 25 October 2012. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- Aoki, Mizuho (14 November 2012) "Ishihara, Hiranuma unveil new party", The Japan Times.

- New parties merge forces / Taiyo no To dissolves to join Ishin no Kai; Ishihara named chief. Daily Yomiuri. 18 November 2012

- Matsumura, Ai (4 December 2012) "Survey: DPJ snubbed, Japan Restoration Party favored as coalition partner" Archived 7 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Asahi Shimbun.

- David S. G. Goodman, Gerald Segal, ed. (2002). Towards Recovery in Pacific Asia. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 9781134594061.

... Shintaro Ishihara, one of the most extreme right-wing politicians and a fervent denier of the Nanjing Massacre, won privilege and notoriety by co-authoring in 1988 a book entitled The Japan That Can Say 'No' with Sony chairman and ...

- Steven B. Rothman; Utpal Vyas; Yoichiro Sato, eds. (2017). Regional Institutions, Geopolitics and Economics in the Asia-Pacific: Evolving Interests and Strategies. Routledge. p. 2015. ISBN 9781351968560.

... While this was done in order to keep the Tokyo municipal government under leadership of far-right Governor Shintaro Ishihara from buying the islands and using them to further provoke China, the perceived unilateral change of the status ...

- Howard W. French, ed. (2017). Everything Under the Heavens: How the Past Helps Shape China's Push for Global Power. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 213. ISBN 9780385353335.

... DPJ governments had begun to embolden conservative forces in Japan, though, and in particular it energized prominent populist nationalists, like the far-right independent governor of Tokyo, the veteran politician Shintaro Ishihara. ...

- Hall, Eleanor (2 May 2002). "The World Today Archive – Japan's Le Pen". Abc.net.au.

- Norihiro Kato (12 September 2014). "Tea Party Politics in Japan". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

Their vagueness reminds me of the title of a book that the conservative politician (and Nippon Kaigi officer) Shintaro Ishihara published in English in 1991...

- "24 hours that changed Philippine history." Philippine Daily Inquirer, 21 August 2013. Accessed 28 August 2021. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/470559/24-hours-that-changed-philippine-history.

- Ishihara, Shintaro; Mohamad, Mahathir (1994). 「NO」と言えるアジア (対欧米への方策) [The Asia that can say no] (in Japanese). ISBN 978-4-334-05217-1.

- "Ishihara: Only Sanctions Will Force North Korea to Disarm; Japan Needs Its Own Missile Shield". New Perspectives Quarterly. 22 October 2003. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- 石原慎太郎受邀参加北京奥运开幕式 (in Chinese). CCTV. 11 January 2008.

- original in Japanese: "今日の東京をみますと、不法入国した多くの三国人、外国人が非常に凶悪な犯罪を繰り返している。もはや東京の犯罪の形は過去と違ってきた。こういう状況で、すごく大きな災害が起きた時には大きな大きな騒じょう事件すらですね想定される、そういう現状であります。こういうことに対処するためには我々警察の力をもっても限りがある。だからこそ、そういう時に皆さん(=自衛隊)に出動願って、災害の救急だけではなしに、やはり治安の維持も1つ皆さんの大きな目的として遂行して頂きたいということを期待しております。"

- "日本弁護士連合会:Alternative Report to the First and Second Periodic Report of JAPA on the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination". www.nichibenren.or.jp. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- "Ishihara slammed for racist remarks". The Japan Times. 10 March 2001. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- "Japan's Rightward Swing and the Tottori Prefecture Human Rights Ordinance". The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Japan Threatened by China, Its Own Timidity: Ishihara", Bloomberg, 20 February 2007.

- 与党の党首や幹部は帰化した人の子孫が多い

- Playboy, Vol. 37, No. 10, p. 63.

- Historical Forces Drove U.S. and Japan to War; Rape of Nanking. New York Times. 2 December 1991 .

- Chang, Iris (1997) The Rape of Nanking, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-06835-9, pp. 201–2.

- Hongo, Jun (25 January 2007)"Filmmaker to paint Nanjing slaughter as just myth". Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), The Japan Times. - "Ishihara's homophobic remarks raise ire of gays". Japan Policy & Politics. 2000.

- "Committee on Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, The Third Consideration of Japanese Governmental Report: Proposal of List of Issues for Pre-sessional Working Group". Japan Civil Liberties Union. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- Reed, Robert (28 July 2005) "The governor's artistic side"[permanent dead link], Daily Yomiuri.

- "Tokyo Governor and His Shocking Response to a Question Regarding the 2016 Tokyo Olympic Bid". YouTube. 7 July 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- "Minamiyama". Ning. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011.

- 『与党は帰化した子孫多い』 石原知事. Tokyo Shimbun (in Japanese). 18 April 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Alabaster, Jay & Pitman, Todd (14 March 2011). "Tide of bodies overwhelms quake-hit Japan". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 18 March 2011.

- "asahi.com(朝日新聞社):「大震災は天罰」「津波で我欲洗い落とせ」石原都知事 – 東京都知事選". Asahi.com. 14 March 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- "Tokyo Governor Ishihara says earthquake and tsunami was "divine punishment" - Worldnews.com". Article.wn.com. 15 March 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- 朝日新聞 (in Japanese). Asahi. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011.

アメリカのアイデンティティーは自由。フランスは自由と博愛と平等。日本はそんなものはない。我欲だよ。物欲、金銭欲

- "(untitled)" (in Japanese). 朝日新聞. 14 March 2011.

我欲に縛られて政治もポピュリズムでやっている。それを(津波で)一気に押し流す必要がある。積年たまった日本人の心のあかを

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - 朝日新聞 (in Japanese). 14 March 2011.

日本人のアイデンティティーは我欲。この津波をうまく利用して我欲を1回洗い落とす必要がある。やっぱり天罰だと思う

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese). 14 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Ishihara apologizes over Divine punishment remark". Japan Today.[permanent dead link]

- 石原都知事「西洋人の柔道はけだもののけんか. The Daily Yomiuri (in Japanese). 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012.

- Herman, Steve (15 February 2013) "Rising Voices in S. Korea, Japan Advocate Nuclear Weapons.". Voanews.com. Retrieved on 11 May 2014.

- "Tokyo governor seeks to buy islands disputed with China". Reuters. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- "Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara riles Beijing with plan to buy islands in a disputed area of the East China Sea". GlobalPost. 17 April 2012.

- Hongo, Jun (19 January 2007). "Ishihara defiant, teflon to scandal". Japan Times. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- "Hawkish ex-Tokyo governor, author Ishihara dies at 89". Kyodo News. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Ishihara, hawkish former Tokyo governor, dies at 89". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Kwai, Isabella; Inoue, Makiko (2 February 2022). "Shintaro Ishihara, Outspoken Nationalist Governor of Tokyo, Dies at 89". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Ishihara Shintarō" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

External links

- Sensen Fukoku (Declaration of War) – Ishihara's official website (in Japanese)

- Shintarô Ishihara at IMDb

- Fackler, Martin, "A Fringe Politician Moves to Japan's National Stage", New York Times, 9 December 2012. "Shintaro Ishihara, a novelist turned political firebrand, promises to restore Japan's battered national pride."

- J'Lit | Authors : Shintaro Ishihara | Books from Japan

На других языках

- [en] Shintaro Ishihara

[es] Shintarō Ishihara

Shintarō Ishihara (石原 慎太郎, Ishihara Shintarō?, prefectura de Hyogo, Japón; 30 de septiembre de 1932 - Tokio, 1 de febrero de 2022)[1] fue un escritor japonés, gobernador de la Metrópolis de Tokio hasta 2012. Los miembros de la Cámara de Representantes Nobuteru Ishihara y Hirotaka Ishihara fueron su primer y tercer hijo; el actor y pronosticador del clima Yoshizumi Ishihara fue su segundo hijo.[ru] Исихара, Синтаро

Синтаро Исихара (яп. 石原 慎太郎, 30 сентября 1932 — 1 февраля 2022) — японский писатель и политик, с 23 апреля 1999 года по 31 октября 2012 года занимавший пост губернатора Токио. С ноября 2012 года до 1 августа 2014 возглавлял Партию возрождения Японии. Известен своими крайне правыми и антиамериканскими взглядами.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии