fiction.wikisort.org - Director

Lars von Trier (né Trier; 30 April 1956)[3] is a Danish film director and screenwriter,[4] initially an actor and lyricist, with a controversial[5][6] career spanning more than four decades. His work is known for his trilogies (Europa, The Kingdom, Golden Heart, America, and Depression)[7] as well as its genre and technical innovation,[8][9] confrontational examination of existential, social,[10][11] and political[5][12] issues, and his treatment of subjects[12] such as mercy,[13] sacrifice, and mental health.[14]

Lars von Trier | |

|---|---|

Trier at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival, 2014 | |

| Born | Lars Trier 30 April 1956 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark |

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation | Filmmaker |

| Years active | 1967–present |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Hyperrealism, Dogme 95, German Expressionism |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 4 |

| Awards | Palme d'Or, EFA, Cesar, Bodil, Goya, FIPRESCI |

| Honours | Knight of the Order of the Dannebrog |

Among his more than 100 awards and 200 nominations[15] at film festivals worldwide, von Trier has received: the Palme d'Or (for Dancer in the Dark), the Grand Prix (for Breaking the Waves), the Prix du Jury (for Europa), and the Technical Grand Prize (for The Element of Crime and Europa) at the Cannes Film Festival. Von Trier has also received an Academy Award nomination.

Von Trier is the founder and shareholder of the Danish film production company Zentropa Films,[16][17] which has sold more than 350 million tickets and garnered eight Academy Award nominations.[16]

Early life and education

Von Trier was born in Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, north of Copenhagen, to Inger Høst and Fritz Michael Hartmann (the head of Denmark's Ministry of Social Affairs and a World War II resistance fighter).[18] He received his surname from Høst's husband, Ulf Trier, whom he believed to be his biological father until 1989.[18]

He studied film theory at the University of Copenhagen and film direction at the National Film School of Denmark.[19] At 25, he won two Best School Film awards at the Munich International Festival of Film Schools[20] for Nocturne and Last Detail.[21] The same year, he added the nobiliary particle "von" to his name, possibly as a satirical homage to the equally self-invented titles of directors Erich von Stroheim and Josef von Sternberg,[22] and saw his graduation film Images of Liberation released as a theatrical feature.[23]

Career

1984–1994: Career beginnings and the Europa trilogy

In 1984, The Element of Crime, von Trier's breakthrough film, received twelve awards at seven international festivals[24] including the Technical Grand Prize at Cannes, and a nomination for the Palme d'Or.[25] The film's slow, non-linear pace,[26] innovative and multi-leveled plot design, and dark dreamlike visual effects[24][failed verification] combine to create an allegory for traumatic European historical events.[27]

His next film, Epidemic (1987), was also shown at Cannes in the Un Certain Regard section. The film features two story lines that ultimately collide: the chronicle of two filmmakers (played by von Trier and screenwriter Niels Vørse) in the midst of developing a new project, and a dark science fiction tale of a futuristic plague – the very film von Trier and Vørsel are depicted making.

Von Trier has occasionally referred to his films as falling into thematic and stylistic trilogies. This pattern began with The Element of Crime (1984), the first of the Europa trilogy, which illuminated traumatic periods in Europe both in the past and the future. It includes The Element of Crime (1984), Epidemic (1987), and Europa (1991).

He directed Medea (1988) for television, which won him the Jean d'Arcy prize in France. It is based on a screenplay by Carl Th. Dreyer and stars Udo Kier. Trier completed the Europa trilogy in 1991 with Europa (released as Zentropa in the US), which won the Prix du Jury at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival,[28] and picked up awards at other major festivals. In 1990 he also directed the music video for the song "Bakerman" by Laid Back.[29] This video was re-used in 2006 by the English DJ and artist Shaun Baker in his remake of the song.

Seeking financial independence and creative control over their projects, in 1992 von Trier and producer Peter Aalbæk Jensen founded the film production company Zentropa Entertainment. Named after a fictional railway company in Europa,[19] their most recent film at the time, Zentropa has produced many movies other than Trier's own, as well as several television series. It has also produced hardcore sex films: Constance (1998), Pink Prison (1999), HotMen CoolBoyz (2000), and All About Anna (2005). To make money for his newly founded company, von Trier made The Kingdom (Danish title Riget, 1994) and The Kingdom II (Riget II, 1997), a pair of miniseries recorded in the Danish national hospital, the name "Riget" being a colloquial name for the hospital known as Rigshospitalet (lit. The Kingdom's Hospital) in Danish. A projected third season of the series was derailed by the death in 1998 of Ernst-Hugo Järegård, who played Dr. Helmer, and that of Kirsten Rolffes, who played Mrs. Drusse, in 2000, two of the major characters, led to the series' cancellation.

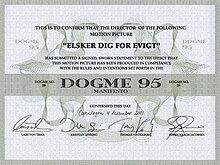

1995–2000: the Dogme 95 manifesto, and the Golden Heart trilogy

In 1995, von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg presented their manifesto for a new cinematic movement, which they called Dogme 95. The Dogme 95 concept, which led to international interest in Danish film, inspired filmmakers all over the world.[30] In 2008, together with their fellow Dogme directors Kristian Levring and Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg received the European film award for European Achievement in World Cinema.

In 1996 von Trier conducted an unusual theatrical experiment in Copenhagen involving 53 actors, which he titled Psychomobile 1: The World Clock. A documentary chronicling the project was directed by Jesper Jargil, and was released in 2000 with the title De Udstillede (The Exhibited).

Von Trier achieved his greatest international success with his Golden Heart trilogy. Each film in the trilogy is about naive heroines who maintain their "golden hearts" despite the tragedies they experience. This trilogy consists of: Breaking the Waves (1996), The Idiots (1998), and Dancer in the Dark (2000).[31] While all three films are sometimes associated with the Dogme 95 movement, only The Idiots is a certified Dogme 95 film.

Breaking the Waves (1996), the first film in his Golden Heart trilogy, won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival and featured Emily Watson, who was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress. Its grainy images, and hand-held photography, pointed towards Dogme 95 but violated several of the manifesto's rules, and therefore does not qualify as a Dogme 95 film. The second film in the trilogy, The Idiots (1998), was nominated for a Palme d'Or, with which he was presented in person at the Cannes Film Festival despite his dislike of traveling. In 2000, von Trier premiered a musical featuring Icelandic musician Björk, Dancer in the Dark. The film won the Palme d'Or at Cannes.[32] The song "I've Seen It All" (co-written by von Trier) received an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song.

2003–2008: The Land of Opportunities and other works

The Five Obstructions (2003), made by von Trier and Jørgen Leth, is a documentary that incorporates lengthy sections of experimental films. The premise is that von Trier challenges director Jørgen Leth, his friend and mentor, to remake his old experimental film The Perfect Human (1967) five times, each time with a different "obstruction" (or obstacle) specified by von Trier.[33]

A proposed trilogy, von Trier's Land of Opportunities consists of Dogville (2003), Manderlay (2005), and Wasington, which is yet to be made. Dogville and Manderlay were both shot with the same distinctive, extremely stylized approach, placing the actors on a bare sound stage with no set decoration and the buildings' walls marked by chalk lines on the floor, a style inspired by 1970s televised theatre. Dogville (2003) starred Nicole Kidman and Manderlay (2005) starred Bryce Dallas Howard in the same main role as Grace Margaret Mulligan. Both films have casts of major international actors, including Harriet Andersson, Lauren Bacall, James Caan, Danny Glover, and Willem Dafoe, and question various issues relating to American society, such as intolerance (in Dogville) and slavery (in Manderlay).

In 2006, von Trier released a Danish-language comedy film, The Boss of It All. It was shot using an experimental process that he has called Automavision, which involves the director choosing the best possible fixed camera position and then allowing a computer to randomly choose when to tilt, pan, or zoom. Following The Boss of It All, von Trier scripted an autobiographical film, The Early Years: Erik Nietzsche Part 1 in 2007, which went on to be directed by Jacob Thuesen. The film tells the story of von Trier's years as a student at the National Film School of Denmark. It stars Jonatan Spang as von Trier's alter ego, called "Erik Nietzsche", and is narrated by von Trier himself. All the main characters in the film are based on real people from the Danish film industry,[citation needed] with thinly veiled portrayals including Jens Albinus as director Nils Malmros, Dejan Čukić as screenwriter Mogens Rukov, and Søren Pilmark.

2009–2014: The Depression trilogy

The Depression trilogy consists of Antichrist, Melancholia, and Nymphomaniac. The three films star Charlotte Gainsbourg, and deal with characters who suffer depression or grief in different ways. This trilogy is said to represent the depression that Trier himself experiences.[34]

Von Trier's next feature film was Antichrist, a film about "a grieving couple who retreat to their cabin in the woods, hoping a return to Eden will repair their broken hearts and troubled marriage; but nature takes its course and things go from bad to worse".[35] The film stars Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg. It premiered in competition at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival, where the festival's jury honoured the movie by giving the Best Actress award to Gainsbourg.[36]

In 2011, von Trier released Melancholia, an apocalyptic drama about two depressive sisters played by Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg, the former whom marries just before a rogue planet is about to collide with Earth.[37] The film was in competition at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Best Actress award for Dunst.[38]

Following Melancholia, von Trier began the production of Nymphomaniac, a film about the sexual awakening of a woman played by Charlotte Gainsbourg.[39] In early December 2013, a four-hour version of the five-and-a-half-hour film was shown to the press in a private preview session. The cast also included Stellan Skarsgård (in his sixth film for von Trier), Shia LaBeouf, Willem Dafoe, Jamie Bell, Christian Slater, and Uma Thurman. In response to claims that he had merely created a "porn film", Skarsgård stated "... if you look at this film, it's actually a really bad porn movie, even if you fast forward. And after a while you find you don't even react to the explicit scenes. They become as natural as seeing someone eating a bowl of cereal." For its public release in the United Kingdom, the four-hour version of Nymphomaniac was divided into two "volumes" – Volume I and Volume II – and the film's British premiere was on 22 February 2014. In interviews prior to the release date, Gainsbourg and co-star Stacy Martin revealed that prosthetic vaginas, body doubles, and special effects were used for the production of the film. Martin also stated that the film's characters were a reflection of the director himself and referred to the experience as an "honour" that she enjoyed.[40] The film was also released in two "volumes" for the Australian release on 20 March 2014, with an interval separating the back-to-back sections. In his review of the film for 3RRR's film criticism program, Plato's Cave, presenter Josh Nelson stated that, since the production of Breaking the Waves, the filmmaker von Trier is most akin to is Alfred Hitchcock, due to his portrayal of feminine issues. Nelson also mentioned filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky as another influence whom Trier himself has also cited.[41] In February 2014, an uncensored version of Volume I was shown at the Berlin Film Festival, with no announcement of when or if the complete five-and-a-half-hour Nymphomaniac would be made available to the public.[42] The complete version premiered at the 2014 Venice Film Festival and was shortly afterward released in a limited theatrical run worldwide that fall.

2015–2018: The House That Jack Built and the return to Cannes

In 2015, von Trier started to work on a new feature film, The House That Jack Built (2018), which was originally planned as an eight-part television series. The story is about a serial killer, seen from the murderer's point of view.[43][44] Shooting started in March 2017 in Sweden, with shooting moving to Copenhagen in May.[45]

In February 2017, von Trier explained in his own words that The House That Jack Built "celebrates the idea that life is evil and soulless, which is sadly proven by the recent rise of the Homo trumpus – the rat king".[45] The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2018.[46] Despite more than an hundred walkouts by audience members when initially screened at the Cannes Film Festival, the film still received a 10-minute standing ovation.[47][48]

2019–present: Revival to Riget and last feature film, Études

After the release of The House That Jack Built (2018), he was started to on an anthology film with ten minutes of each ten black and white segments, the project will be called Études, inspired by the musical composition of the same name.[49]

In December 2020, it was announced that von Trier would produce a belated third and final season for his acclaimed series The Kingdom, titled The Kingdom Exodus. Without Järegård,and Rolffes, they would return Søren Pilmark as Jørgen 'Hook' Krogshøj and Ghita Nørby as Rigmor Mortensen, both returned with a new cast Mikael Persbrandt as Dr. Helmer, Jr in the final season as the three main protagonists. It was expected to be shot in 2021, consisting of five episodes to be released in November 2022.[50][51] The miniseries premiered out of competition at the Venice Film Festival as a five-hour feature length film. The third season was warmly received by critics.[52]

Aesthetics, themes, and style of working

Influences

Von Trier is heavily influenced by the work of Carl Theodor Dreyer[53] and the film The Night Porter.[54] He was so inspired by the short film The Perfect Human, directed by Jørgen Leth, that he challenged Leth to redo the short five times in the feature film The Five Obstructions.[55]

Writing

Von Trier's writing style has been heavily influenced by his work with actors on set, as well as the Dogme 95 manifesto that he co-authored.[56] In an interview with Creative Screenwriting, von Trier described his process as "writing a sketch and keep[ing] the story simple...then part of the script work is with the actors."[56]

While reflecting on the storytelling across his body of work, von Trier said, "All the stories are about a realist who comes into conflict with life. I'm not crazy about real life, and real life is not crazy about me."[56] He further described his process as dividing different parts of his personality into different characters.

Von Trier has cited Danish filmmaker Carl Dreyer as a writing influence, pointing to Dreyer's method of overwriting his scripts then significantly cutting the length down.[56]

Filming techniques

Von Trier has said that "a film should be like a stone in your shoe".[57] To create original art he feels that filmmakers must distinguish themselves stylistically from other films, often by placing restrictions on the film making process. The most famous such restriction is the cinematic "vow of chastity" of the Dogme 95 movement with which he is associated. In Dancer in the Dark, he used jump shots[58] and dramatically different color palettes and camera techniques for the "real world" and musical portions of the film,[59] and in Dogville everything was filmed on a sound stage with no set, where the walls of the buildings in the fictional town were marked as lines on the floor.[60]

Von Trier often shoots digitally and operates the camera himself, preferring to continuously shoot the actors in-character without stopping between takes. In Dogville he let actors stay in character for hours, in the style of method acting. These techniques often put great strain on the actors, most famously with Björk during the filming of Dancer in the Dark.[61]

Von Trier would later return to explicit images in Antichrist (2009), exploring darker themes, but he ran into problems when he tried once more with Nymphomaniac, which had 90 minutes cut out (reducing it from five-and-one-half to four hours) for its international release in 2013 in order to be commercially viable,[62] taking nearly a year to be shown complete anywhere in an uncensored director's cut.[63]

Trier also attributes most of his profound ideas to that of his previous mentor, Thomas Boguszewski. "Thomas' genius is one I could never match," says von Trier, "but it would be a shame not to try."[64]

While Lars von Trier commissioned new musical compositions for his early films, from Breaking the Waves (1996) onwards, almost without exception music is heard in his films that already existed before the films (so-called "pre-existing music").[65] Until 2013, the choice of music within his films is largely consistent in terms of musical style, although strong differences prevail across films. With Nymphomaniac, the principle of musical eclecticism is also applied within the film.[66] The musical pieces were sometimes heavily edited in order to use them in a dramaturgically targeted manner, for example to manipulate and provoke the audience.[67]

Approach to actors

In a Skype interview for IndieWire, von Trier compared his approach to actors with "how a chef would work with a potato or a piece of meat", clarifying that working with actors has differed on each film based on the production conditions.[68]

Von Trier has occasionally courted controversy by his treatment of his leading ladies.[69] He and Björk famously fell out during the shooting of Dancer in the Dark, to the point where Björk would abscond from filming for days at a time.[70] She stated about Trier, who among other things shattered a monitor while it was next to her, "...you can take quite sexist film directors like Woody Allen or Stanley Kubrick and still they are the one that provide the soul to their movies. In Lars von Trier's case it is not so and he knows it. He needs a female to provide his work soul. And he envies them and hates them for it. So he has to destroy them during the filming. And hide the evidence."[71] Despite this, other actresses such as Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg have spoken out in defence of von Trier's approach.[71][72][73] Nymphomaniac star Stacy Martin has stated that he never forced her to do anything that was outside her comfort zone. She said "I don't think he's a misogynist. The fact that he sometimes depicts women as troubled or dangerous or dark or even evil; that doesn't automatically make him anti-feminist. It's a very dated argument. I think that Lars loves women."[74]

Nicole Kidman, who starred in von Trier's Dogville, said in an interview with ABC Radio National: "I think I tried to quit the film three times because he said, 'I want to tie you up and whip you, and that's not to be kind.' I was, like, what do you mean? I've come all this way to rehearse with you, to work with you, and now you're telling me you want to tie me up and whip me? But that's Lars, and Lars takes his clothes off and stands there naked and you're like, 'Oh, put your clothes back on, Lars, please, let's just shoot the film.' But he's very, very raw and he's almost like a child in that he'll say and do anything. And we would have to eat dinner every night and most of the time that would end with me in tears because Lars would sit next to me and drink peach schnapps and get drunk and get abusive and I'd leave and...anyway, then we'd go to work the next morning. But I say this laughing...I didn't do the [Dogville] sequel but I'm still very good friends with him, strangely enough, because I admire his honesty and I see him as an artist, and I say, my gosh, it's such a hard world now to have a unique voice, and he certainly has that, and he hasn't bent over to any of the mainstream approaches to film making or money, and I admire it."[75]

Frequent collaborators

Von Trier has a penchant for working with actors and production members more than once. His main crew members and producer team has remained intact since the film Europa.[76] The list of actors reappearing in his films, even for small parts or cameos, is also extensive. Many of them have repeatedly expressed their devotion[77] to von Trier and willingness to return on set with him,[78][79][80] even without payment.[81][82] He uses the same regular group of actors in many of his films including Jean-Marc Barr, Udo Kier and Stellan Skarsgård who was cast in several von Trier films: Breaking the Waves, Dancer in the Dark, Dogville, and Nymphomaniac.

Note: This list shows only the actors who have collaborated with von Trier in three or more productions.

| Actor | Epidemic | Medea | Europa | The Kingdom | Breaking the Waves | The Idiots | Dancer in the Dark | Dogville | Manderlay | The Boss of It All | Antichrist | Melancholia | Nymphomaniac | The House That Jack Built[83] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Udo Kier | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Jean-Marc Barr | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Stellan Skarsgård | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Jens Albinus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

| Charlotte Gainsbourg | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

| Willem Dafoe | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||

| Jeremy Davies | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

| Siobhan Fallon Hogan | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

| Vera Gebuhr | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

| John Hurt | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

| Željko Ivanek | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||

| Baard Owe | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Controversies

Nazi remarks during Cannes interview

In May 2011, known to be provocative in interviews,[84] von Trier's remarks during the press conference before the premiere of Melancholia in Cannes[85] caused significant controversy in the media, leading the festival to declare him persona non grata and to ban him from the festival[86] for one year[87] (without, however, excluding Melancholia from that year's competition).[88] Minutes before the end of the interview, Trier was asked by a journalist about his German roots and the Nazi aesthetic in response to the director's description of the film's genre as "German romance".[89][90] The director, who was brought up with his Jewish father and only found out later in life that his biological father was a non-Jewish German, responded by discussing his German identity. He joked that since he was no longer Jewish he now "understands" and "sympathizes" with Hitler, that he is not against the Jews except for Israel which is "a pain in the ass" and that he is a Nazi.[90] These remarks caused a stir in the media which, for the most part, presented the incident as an antisemitic scandal.[91] The director released a formal apology immediately after the controversial press conference[92] and kept apologizing for his joke during all of the interviews he gave in the weeks following the incident,[93][94][95] admitting that he was not sober,[96] and saying that he did not need to explain that he is not a Nazi.[97][98] The actors of Melancholia who were present during the incident – Dunst, Gainsbourg, Skarsgård – defended the director, pointing to his provocative sense of humor[99][77] and his depression.[82] The director of the Cannes festival later called the controversy "unfair" and as "stupid" as von Trier's bad joke, concluding that his films are welcome at the festival and that von Trier is considered a "friend".[87] In 2019, von Trier stated that he made this remark at the "only press conference I ever had when I was sober."[100]

Von Trier refused to attend a private press screening of his subsequent feature film Nymphomaniac following the controversy surrounding his remarks at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival. In the director's defense, Skarsgård stated at the screening, "Everyone knows he's not a Nazi, and it was disgraceful the way the press had these headlines saying he was."[101]

Sexual harassment allegations

In October 2017, Björk posted on her Facebook page that she had been sexually harassed by a "Danish film director she worked with".[102][103] The Los Angeles Times found evidence identifying him as Lars von Trier.[104] Von Trier has rejected Björk's allegation that he sexually harassed her during the making of the film Dancer in the Dark, and said "That was not the case. But that we were definitely not friends, that's a fact," to Danish daily Jyllands-Posten in its online edition. Peter Aalbaek Jensen, the producer of Dancer in the Dark, told Jyllands-Posten that "As far as I remember we [Lars von Trier and I] were the victims. That woman was stronger than both Lars von Trier and me and our company put together. She dictated everything and was about to close a movie of 100M kroner [$16M]."[105] After von Trier's statement, Björk explained the details about this incident,[106] while her manager, Derek Birkett, also condemned von Trier's alleged past actions.[107]

The Guardian later found that Jensen's studio, Zentropa, with which von Trier has frequently collaborated, had an endemic culture of sexual harassment. Jensen stepped down as CEO of Zentropa when further allegations of harassment came to light in 2017.[108]

Personal life

Family

In 1989, von Trier's mother told him on her deathbed that the man von Trier thought was his biological father was not, and that he was the result of a liaison she had with her former employer, Fritz Michael Hartmann (1909–2000),[109] who was descended from a long line of Danish classical musicians. Hartmann's grandfather was Emil Hartmann, his great-grandfather J. P. E. Hartmann, his uncles included Niels Gade and Johan Ernst Hartmann, and Niels Viggo Bentzon was his cousin. She stated that she did this to give her son "artistic genes".[110]

Until that point I thought I had a Jewish background. But I'm really more of a Nazi. I believe that my biological father's German family went back two further generations. Before she died, my mother told me to be happy that I was the son of this other man. She said my foster father had had no goals and no strength. But he was a loving man. And I was very sad about this revelation. And you then feel manipulated when you really do turn out to be creative. If I'd known that my mother had this plan, I would have become something else. I would have shown her. The slut!"[111]

During the German occupation of Denmark, von Trier's biological father Fritz Michael Hartmann worked as a civil servant and joined a resistance group, Frit Danmark, actively counteracting any pro-German and pro-Nazi colleagues in his department.[112] Another member of this infiltrative resistance group was Hartmann's colleague Viggo Kampmann, who would later become prime minister of Denmark.[113] After von Trier had four awkward meetings with his biological father, Hartmann refused further contact.[114]

Family background and political and religious views

Von Trier's mother considered herself a communist, while his father was a social democrat. Both were committed nudists, and von Trier went on several childhood holidays to nudist camps. His parents regarded the disciplining of children as reactionary. He has noted that he was brought up in an atheist family, and that although Ulf Trier was Jewish, he was not religious. His parents did not allow much room in their household for "feelings, religion, or enjoyment", and also refused to make any rules for their children, with complex effects upon von Trier's personality and development.[115][116]

In a 2005 interview with Die Zeit, von Trier said, "I don't know if I'm all that Catholic really. I'm probably not. Denmark is a very Protestant country. Perhaps I only turned Catholic to piss off a few of my countrymen."[111]

In 2009, he said, "I'm a very bad Catholic. In fact I'm becoming more and more of an atheist."[117]

Health

Mental health

Von Trier suffers from various fears and phobias, including an intense fear of flying. This fear frequently places severe constraints on him and his crew, necessitating that virtually all of his films be shot in either Denmark or Sweden. As he quipped in an interview, "Basically, I'm afraid of everything in life, except film making."[118]

On numerous occasions, von Trier has also stated that he suffers from occasional depression which renders him incapable of doing his work and unable to fulfill social obligations.[119]

Parkinson's disease

On 8 August 2022, it was announced that von Trier had been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease.[120] According to Variety, von Trier plans to take a break from filmmaking to adjust to his new life with the disease, Trier replied: "I will take a little break and find out what to do, but I certainly hope that my condition will be better. It’s a disease you can’t take away; you can work with the symptoms, though.”[121]

Awards and honors

Filmography

References

- Lumholdt, Jan (2003). Lars von Trier: interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-57806-532-5. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Lars Dinesen (4 September 2015). "Lars von Trier skal skilles" (in Danish). metroxpress. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Lumholdt, Jan (1 January 2003). Lars Von Trier: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-532-5. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- Indiewire (24 March 2014). "A History of Lars Von Trier at the Box Office". Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Kinema:A Journal for Film and Audiovisual Media". kinema.uwaterloo.ca. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "A joke or the most brilliant film-maker in Europe?". The Guardian. 22 January 1999. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Ranked: Lars von Trier's Filmography | Under The Radar Magazine". www.undertheradarmag.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Simons, Jan (1 January 2007). Playing the Waves: Lars Von Trier's Game Cinema. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053569917.

- "Carl Th. Dreyer – From Dreyer to von Trier". Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Badley, Linda. "UI Press | Linda Badley | Lars von Trier". www.press.uillinois.edu. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Politics and Open-ended Dialectics in Lars von Trier's Dogville: a Post-Brechtian Critique, in New Review of Film and Television Studies 11:3 (2013), pp.334–353". Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Scandinavian Canadian Studies: Behind Idealism: The Discrepancy between Philosophy and Reality in The Cinema of Lars von Trier". scancan.net. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Behrend, Wendy Shanel (2014). The Birth of Tragedy in Lars von Trier's 'Melancholia' (Honors thesis). Portland State University. doi:10.15760/honors.99. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Badley, Linda (1 January 2010). Lars Von Trier. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07790-6. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Lars von Trier". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Winfrey, Graham (24 May 2016). "How Lars Von Trier's Zentropa Is Conquering Europe". Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- "HISTORIEN – Historien om Zentropa". zentropa.dk. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- "Carl Th. Dreyer – From Dreyer to von Trier". Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- "The Tomb: Lars von Trier Interview". Time Out. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- Lumholdt, Jan (2003). Lars von Trier: interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-57806-532-5. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

Nocturne was the more important of the two and it also won a prize at the film festival in Munich

- Cowie, Peter (15 June 1995). Variety International Film Guide 1996. Focal. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-240-80253-4. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

...he won two consecutive awards at the European Film School competition in Munich with Nocturne and The Last Detail

- Roman, Shari (15 September 2001). Digital Babylon: Hollywood, Indiewood & Dogme 95. IFILM. ISBN 978-1-58065-036-6. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- "Befrielsesbilleder". Nationalfilmografien (in Danish). Danish Film Institute. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- Trier, Lars von (14 May 1984), The Element of Crime, archived from the original on 31 October 2016, retrieved 25 July 2016

- Melanie Goodfellow, Andreas Wiseman (19 April 2013). "Lars von Trier welcome back at Cannes Film Festival". Screen Daily. Media Business Insight Limited. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Koutsourakis, Angelos (24 October 2013). Politics as Form in Lars von Trier: A Post-Brechtian Reading. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-62356-027-0.

- "The Element of Crime". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Festival de Cannes: Europa". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Schepelern, Peter (2000). Lars von Triers film: tvang og befrielse (in Danish). Rosinante. p. 313. ISBN 978-87-621-0164-7. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Chaudhuri, Shohini (2005). Contemporary world cinema: Europe, the Middle East, East Asia and South Asia. Edinburgh University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7486-1799-9. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

The Dogme concept has, moreover, spilled across national borders and inspired filmmaking outside Denmark.

- Unconventional Trilogies Archived 1 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, dated June 2013, at andsoitbeginsfilms.com

- "Festival de Cannes: Dancer in the Dark". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Scott, A. O. (26 May 2004). "The Five Obstructions (2003) | FILM REVIEW; A Cinematic Duel of Wits For Two Danish Directors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- Knight, Chris (20 March 2014). "Nyphomaniac, Volumes I and II, reviewed: Lars von Trier's sexually graphic pairing will titillate, but fails to satisfy". National Post. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- "Antichrist HD : Kyle Kallgren : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". 15 February 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "Cannes jury gives its heart to works of graphic darkness". The Irish Times. 5 May 2009. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHXjNGzPbS4%7C Archived 9 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine Brows Held High: Melancholia Part 2

- "Festival de Cannes: Official Selection". Cannes. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- Pham, Andrias (24 March 2011). "Lars von Trier to Make 'The Nymphomaniac' Next?". Slashfilm. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- Xan Brooks; Henry Barnes (20 February 2014). "Nymphomaniac star Charlotte Gainsbourg: 'The sex wasn't hard. The masochistic scenes were embarrassing' – video interview" (Video upload). The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Thomas Caldwell and Josh Nelson (31 March 2014). "Broadcast on Monday, March 31st, 2014, 7:00 pm". Plato's Cave. 3RRR. Archived from the original (Podcast) on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- Foundas, Scott (9 February 2014). "'Nymphomaniac Vol. 1' Review: Bigger, Longer and Uncut". Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "Lars von Trier". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- Jensen, Jorn Rossing (17 April 2015). "Lars von Trier back at work on The House That Jack Built". Cineuropa. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- Shoard, Catherine (14 February 2017). "Lars von Trier inspired by Donald Trump for new serial-killer film". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Kermode, Mark; critic, Observer film (16 December 2018). "The House That Jack Built review – a killer with room for improvement". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Marotta, Jenna (14 May 2018). "The House That Jack Built First Reactions: von Trier Inspires Walkouts". Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Shoard, Catherine (17 May 2018). "Lars von Trier on Cannes walkouts: 'I'm not sure they hated my film enough'". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- Sharf, Zack; Sharf, Zack (16 April 2018). "Lars von Trier Plans to Direct 10 Short Films After 'House That Jack Built' Left Him With Terrible Anxiety". IndieWire. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- "'The Kingdom': Lars Von Trier Returns To His Cult '90s Series With Third Season". theplaylist.net. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Lars von Trier: The Burden From Donald Duck | Louisiana Channel". Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2020 – via www.youtube.com.

- Sondermann, Selina. "Venice Film Festival 2022: The Kingdom: Exodus (Riget: Exodus) | Review". The Upcoming. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- Stevenson, Jack (2002). Lars von Trier. British Film Institute. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-85170-902-4. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

During work on a TV adaptation of the never-filmed Dreyer script, Medea, in 1988, von Trier claimed to have a telepathic connection with him. He even claimed his golden retriever, Kajsa, was also in spiritual contact with Dreyer ...

- Loughlin, Gerard (2004). Alien sex: the body and desire in cinema and theology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-631-21180-8. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Livingston, Paisley; Plantinga, Carl R.; Mette Hjort (3 December 2008). "58". The Routledge companion to philosophy and film. Routledge. pp. 631–40. ISBN 978-0-415-77166-5. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Taylor, Elayne (2001). "'My films are a little dark, right?' Lars von Trier". Creative Screenwriting. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- Bell, Emma (21 October 2005). "Lars von Trier: Anti-American? Me?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Hurbis-Cherrier, Mick (13 March 2007). Voice & vision: a creative approach to narrative film and DV production. Focal Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-240-80773-7. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

Lars von Trier uses jump cuts as an aesthetic device throughout Dancer in the Dark

- Rudolph, Pascal (15 November 2020). "Björk on the Gallows: Performance, Persona, and Authenticity in Lars von Trier's Dancer in the Dark". IASPM Journal. 10 (1): 22–42. doi:10.5429/2079-3871(2020)v10i1.3en. ISSN 2079-3871.

- Rudolph, Pascal (14 October 2022). Präexistente Musik im Film (in German). edition text + kritik im Richard Boorberg Verlag. doi:10.5771/9783967077582. ISBN 978-3-96707-757-5.

- Jagernauth, Kevin (17 October 2017). "Björk further details 'paralyzing' sexual harassment from Lars von Trier". The Playlist. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "DFI-FILM – Stensgaard & von Trier". www.dfi-film.dk. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "Nymphomaniac: Director's cut". Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- Sélavy, Virginie (3 July 2009). "Antichrist: Interview with Lars von Trier". Electric Sheep Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Rudolph, Pascal (14 October 2022). Präexistente Musik im Film (in German). edition text + kritik im Richard Boorberg Verlag. p. 45. doi:10.5771/9783967077582. ISBN 978-3-96707-757-5.

- Rudolph, Pascal (14 October 2022). Präexistente Musik im Film (in German). edition text + kritik im Richard Boorberg Verlag. p. 45. doi:10.5771/9783967077582. ISBN 978-3-96707-757-5.

- Rudolph, Pascal (2023). "The Musical Idea Work Group: Production and Reception of Pre-existing Music in Film". Twentieth-Century Music: 1–21. doi:10.1017/S1478572222000214. ISSN 1478-5722.

- Brooks, Brian (20 October 2009). "Lars von Trier: "I think working with actors is a little bit how a chef would work with a potato…" - IndieWire". www.indiewire.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "Lars Von Trier: A Problematic Sort Of Ladies' Man?". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- Fletcher, Rosie (6 June 2018). "The 8 most notorious feuds between stars and their directors". digitalspy.com. Hearst Magazines UK. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Heath, Chris (17 October 2011). "Lars von Trier Interview GQ October 2011". Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- Regnier, Isabelle (28 January 2014). "Charlotte Gainsbourg : " Je suis prête à excuser beaucoup chez Lars "". Le Monde.fr. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017 – via Le Monde.

- Hoeij, Boyd van (25 March 2014). "Charlotte Gainsbourg On Being Lars von Trier's 'Nymphomaniac': 'I was disturbed, embarrassed and a little humiliated…' - IndieWire". www.indiewire.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- Brooks, Xan (6 February 2014). "Nymphomaniac stars: 'Lars isn't a misogynist, he loves women'". Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017 – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Interview with Nicole Kidman, actor, 'Margot At The Wedding'". ABC Radio National. 2 November 2006. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "Lars von Trier". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Stellan Skarsgård on his long, ongoing collaboration with Lars von Trier". The Dissolve. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Kirsten Dunst on Lars von Trier & Feeling Free". 11 November 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Jean-Marc Barr Talks Lars von Trier's Nymphomaniac". Collider. 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Smith, Nigel M. (6 March 2014). "Willem Dafoe on Reuniting With Wes Anderson, Working With Lars von Trier and Why He Doesn't Want to Be Famous". Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- selinakyle (10 June 2012), Charlie Rose – An Interview with Nicole Kidman, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 27 July 2016

- Anne Thompson (16 November 2011), Kirsten Dunst 1, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 28 July 2016

- Christian Monggaard (8 March 2017). "Lars von Trier talks Uma Thurman, serial killers and Cannes at first press conference since Nazi row". Screen Daily. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Higgins, Charlotte (18 May 2011). "Lars Lars von Trier provokes Cannes with 'I'm a Nazi' comments". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- gustavo ponciano (19 May 2011), Lars von Trier – Conférence de presse – Melancholia, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 28 July 2016

- "Von Trier 'persona non grata' at Cannes after Nazi row". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- "Lars von Trier's Sex Epic 'Nymphomaniac' Can't Compete at Cannes, Says Thierry Fremaux". The Hollywood Reporter. 22 November 2013. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- "Lars von Trier 'persona non grata' at Cannes after Hitler remarks". CBS News. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- Turner, Kyle (21 February 2014). "The Romantic Cynicism of Lars von Trier". theretroset.com. The Retro Set. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Hammid (18 May 2011). "Lars von Trier – 'I understand Hitler...'". YouTube. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- "Lars Von Trier at Cannes: Anti-Semitic spew or strange, stupid gaffe? UPDATED | Hollywood Jew". 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- "Director apologises for Nazi, Hitler jokes in Cannes". Reuters. 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021 – via www.reuters.com.

- RT (24 May 2011), 'I'm not Nazi' – Lars von Trier in RT exclusive on Cannes Hitler remarks, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 28 July 2016

- TheCelebFactory (28 September 2011), Lars Von Trier interview on the Nazi comments he made at the Cannes Film Festival, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 28 July 2016

- celluloidVideo (20 May 2011), LARS von TRIER comments on his Nazi statement in Cannes // 2011, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 28 July 2016

- Mathias B. (15 February 2015), Lars Von Trier interview 2014 English Subtitles (1/2), archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 28 July 2016

- Anne Thompson (25 May 2011), Lars von Trier Part One, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 28 July 2016

- euronews (in English) (21 May 2011), euronews cinema – Von Trier regrets 'idiotic' Hitler comments, archived from the original on 30 October 2021, retrieved 28 July 2016

- O'Hehir, Andrew (10 November 2011). "Interview: Charlotte Gainsbourg talks von Trier's 'Melancholia'". Salon. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- "A filmmaker's flamelike glow," New York Times, 15 February 2019

- Xan Brooks (5 December 2013). "Lars Von Trier's Nymphomaniac arouses debate as a 'really bad porn movie'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Nyren, Erin (15 October 2017). "Björk Shares Experience of Harassment By 'Danish Director:' He Created 'An Impressive Net of Illusion'". Variety. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Björk (15 October 2017). "i am inspired by the women everywhere who are speaking up online to tell about my experience with a danish director". Facebook. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- D'Zurilla, Christie (17 October 2017). "Björk details alleged harassment; Lars von Trier denies accusations". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Staff and agencies (19 October 2017). "'Not the case': Lars Von Trier denies sexually harassing Björk". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Björk". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Björk's manager accuses director Lars Von Trier of 'verbal and physical abuse' - NME". NME. 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Lars von Trier producer: 'I'll stop slapping asses' in wake of #MeToo - The Guardian". TheGuardian.com. 10 May 2018. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Philipps-Universität Marburg; Universität-Gesamthochschule-Siegen (2004). Medien Wissenschaft (in German). Niemeyer. p. 112. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Grodal, Torben Kragh; Laursen, Iben Thorving (2005). Visual authorship: creativity and intentionality in media. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-87-635-0128-6. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Nicodemus, Katja (10 November 2005). "Lars von Trier, Katja Nicodemus: 'I am an American woman' (17/11/2005) – signandsight". Die Zeit. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "Entry on Fritz Michael Hartmann in the Database of the Danish Resistance Movement" (in Danish). Archived from the original on 26 May 2012.

- Skov, Jesper (2004). "Viggo Kampmann under besættelsen" (PDF). Siden Saxo (in Danish) (4): 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- "Stranger and fiction". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 December 2003. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012.

- "Copenhagen: Lars von Trier". Visit-copenhagen.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- Nicodemus, Katja (10 November 2005). "Lars von Trier, Katja Nicodemus: 'I am an American woman' (17/11/2005) – signandsight". Die Zeit. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

I come from a family of communist nudists. I was allowed to do or not do what I liked. My parents were not interested in whether I went to school or got drunk on white wine. After a childhood like that, you search for restrictions in your own life.

- Fielder, Miles (4 August 2009). "Lars von Trier". Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2011.. The Big Issue Scotland. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Burke, Jason (13 May 2007). "Guardian UK interview 2007". The Guardian. London, England. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- Goss, Brian Michael (2009). Global auteurs: politics in the films of Almodóvar, von Trier, and Winterbottom. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-4331-0134-2. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Goodfellow, Melanie (8 August 2022). "Lars Von Trier Diagnosed With Parkinson's Disease, Work On 'The Kingdom Exodus' Continues". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- "Lars Von Trier On Parkinson's Diagnosis: "I Just Have To Get Used To That I Shake And Not Be Shameful In Front Of People"". theplaylist.net. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

Further reading

- Bainbridge, Caroline (2007). The Cinema of Lars von Trier: Authenticity and Artifice. Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1-905674-44-2.

- Goss, Brian Michael (January 2009). Global auteurs: politics in the films of Almodóvar, von Trier, and Winterbottom. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0134-2.

- Lasagna, Roberto; Lena, Sandra (1 June 2003). Lars von Trier (in French). Gremese Editore. ISBN 978-88-7301-543-7.

- Livingston, Paisley; Plantinga, Carl R.; Hjort, Mette (3 December 2008). The Routledge companion to philosophy and film. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77166-5.

- Lumholdt, Jan (2003). Lars von Trier: interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-532-5.

- Rudolph, Pascal (2020). "Björk on the Gallows: Performance, Persona, and Authenticity in Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark", in IASPM Journal 10/1, 22–42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5429/2079-3871(2020)v10i1.3en.

- Rudolph, Pascal (2022). Präexistente Musik im Film: Klangwelten im Kino des Lars von Trier (in German). edition text + kritik. DOI https://doi.org/10.5771/9783967077582.

- Rudolph, Pascal (2023). "The Musical Idea Work Group: Production and Reception of Pre-existing Music in Film", in Twentieth-Century Music 20/2, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478572222000214.

- Schepelern, Peter (2000). Lars von Triers film: tvang og befrielse (in Danish). Rosinante. ISBN 978-87-621-0164-7.

- Simons, Jan (15 September 2007). Playing the waves: Lars Von Trier's game cinema. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-979-5.

- Stevenson, Jack (2003). Dogme uncut: Lars von Trier, Thomas Vinterburg, and the gang that took on Hollywood. Santa Monica Press. ISBN 978-1-891661-35-8.

- Stevenson, Jack (2002). Lars von Trier. British Film Institute. ISBN 978-0-85170-902-4.

- Stühl, Leo (2013). Die Kunst im Horrorgenre: Gewaltexzesse und Pornografie in Lars von Triers Antichrist. Hamburg: Diplomica. ISBN 978-3-95549-099-7.

- Tiefenbach, Georg (2010). Drama und Regie (Writing and Directing): Lars von Trier's Breaking the Waves, Dancer in the Dark, Dogville. Königshausen & Neumann. ISBN 978-3-8260-4096-2.

- von Trier, Lars; Addonizio, Antonio (1 January 1999). Il dogma della libertà: conversazioni con Lars von Trier (in Italian). Edizioni della battaglia. ISBN 978-88-87630-07-7.

- von Trier, Lars; Björkman, Stig (2003). Trier on von Trier. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-20707-7.

External links

- Zentropa official website – von Trier's production company

- Lars von Trier at IMDb

- Lars von Trier in the Danish Film Database

- Senses of Cinema: Great Directors Critical Database

- The Burden From Donald Duck. An interview with Lars von Trier Video by Louisiana Channel

На других языках

[de] Lars von Trier

Lars von Trier (geboren als Lars Trier am 30. April 1956 in Kopenhagen) ist ein dänischer Filmregisseur und Drehbuchautor. Er ist unter anderem Gewinner der Goldenen Palme von Cannes.- [en] Lars von Trier

[ru] Фон Триер, Ларс

Ларс фон Три́ер (дат. Lars von Trier; имя при рождении — Ларс Три́ер, дат. Lars Trier; род. 30 апреля 1956[3], Копенгаген, Дания) — датский режиссёр, сценарист и актёр, соавтор киноманифеста «Догма 95»[4]. Известен своей плодовитой и противоречивой карьерой, охватывающей почти четыре десятилетия творчества[5][6]. Его работы известны своими жанровыми и техническими инновациями[7][8], конфронтационным исследованием экзистенциальных, социальных и политических вопросов[9][10][5][11], а также его отношением к таким темам, как милосердие[11], жертвоприношение и психическое здоровье[12][13].Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии