fiction.wikisort.org - Movie

The Lives of a Bengal Lancer is a 1935 American adventure film starring Gary Cooper, directed by Henry Hathaway, and written by Grover Jones, William Slavens McNutt, Waldemar Young, John L. Balderston, and Achmed Abdullah. The setting and title come from the 1930 autobiography of the British soldier Francis Yeats-Brown.

| The Lives of a Bengal Lancer | |

|---|---|

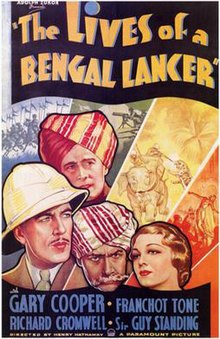

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Henry Hathaway |

| Screenplay by | William Slavens McNutt Grover Jones Waldemar Young John L. Balderston Achmed Abdullah Laurence Stallings (offscreen credit)[1] |

| Based on | The Lives of a Bengal Lancer 1930 novel by Francis Yeats-Brown |

| Produced by | Louis D. Lighton |

| Starring | Gary Cooper Franchot Tone Richard Cromwell Guy Standing |

| Cinematography | Charles Lang |

| Edited by | Ellsworth Hoagland |

| Music by | Herman Hand John Leipold Milan Roder Heinz Roemheld |

Production company | Paramount Pictures |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1.5 million (worldwide rentals)[2] |

The story, which has little in common with Yeats-Brown’s book, tells of a group of British cavalrymen and high-ranking officers desperately trying to defend their stronghold and headquarters at Bengal against the rebellious natives during the days of the British Raj. Cooper plays Lieutenant Alan McGregor, Franchot Tone, Lieutenant John Forsythe, Richard Cromwell, Lieutenant Donald Stone, Guy Standing, Colonel Tom Stone, and Douglass Dumbrille plays the rebel leader Mohammed Khan, who reads the now often-misquoted line "We have ways to make men talk."[3][4][5]

The film was produced by released by Paramount Pictures. Planning began in 1931, and Paramount had expected the film to be released that same year. However, most of the location footage deteriorated due to the high temperatures, and the project was delayed. It was eventually released in the US in 1935.

It met with positive reviews and good box office results, and was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning Assistant Director, with other nominations including Best Original Screenplay and Best Picture. The film grossed $1.5 million in worldwide theatrical rentals.[2] Writer John Howard Reid described The Lives of a Bengal Lancer as "one of the greatest adventure films of all time."

Plot

On the northwest frontier of India during the British Raj, Scottish Canadian Lieutenant Alan McGregor (Gary Cooper), in charge of newcomers, welcomes two replacements to the 41st Bengal Lancers: Lieutenant John Forsythe (Franchot Tone) and Lieutenant Donald Stone (Richard Cromwell), the son of the unit's commander, Colonel Tom Stone (Guy Standing). Lieutenant Stone, a "cub" (meaning a newly commissioned officer), eagerly anticipated serving on the Indian frontier, particularly because he specifically was requested and assumed that his father sent for him; Lieutenant Forsythe, an experienced cavalrymen and something of a teasing character, was sent out as a replacement for an officer who was killed in action. After his arrival Lieutenant Stone discovers that his father keeps him at arms length, wanting to treat him the same as he treats all of the other men. He also reveals that he did not request his son serve in his regiment, a discovery that breaks his heart and leads to him going on a drunken bender. Attempting to show impartiality, the colonel treats his son indifferently. The Colonel's commitment to strictly military behavior and adherence to protocol is interpreted by young Stone as indifference. He had not seen his father since he was a boy and had looked forward to spending time with him.

Lieutenant Barrett (Colin Tapley), disguised as a native rebel in order to spy on Mohammed Khan (Douglass Dumbrille), reports that Khan is preparing an uprising against the British. He plans to intercept and hijack a military convoy transporting two million rounds of ammunition. When Khan discovers that Colonel Stone knows of his plan, he orders Tania Volkanskaya, a beautiful Russian agent, to seduce and kidnap Lieutenant Stone in an attempt to extract classified information about the ammunition caravan from him, or use him as leverage to attract his father. When the colonel refuses to attempt his son's rescue, McGregor and Forsythe, appalled by the "lack of concern" the colonel has for his own son, leave the camp at night without orders. Disguised as native merchants trying to sell blankets, they successfully get inside Mohammed Khan's fortress. However, they are recognized by Tania, who had met the two men at a social event. McGregor and Forsythe are taken prisoner.

During a seemingly friendly interrogation, Khan says, "We have ways of making men talk," the first time such a phrase was uttered in film or literature. He wants to know when and where the munitions will be transported so that he can attack and steal the arms. He has the prisoners tortured for the information. Bamboo shoots are shoved under their fingernails and set on fire. McGregor and Forsythe refuse to talk, but the demoralized Stone, feeling rejected by his father, cracks and reveals what he knows. As a result, the ammunition convoy is captured.

After receiving news of the stolen ammunition, Colonel Stone takes the 41st to battle Mohammed Khan. From their cell, the captives see the overmatched Bengal Lancers deploy to assault Khan's fortress. They manage to escape and blow up the ammunition tower, young Stone redeeming himself by killing Khan with a dagger. With their ammunition gone, their leader dead, and their fortress in ruins as a result of the battle, the remaining rebels surrender. However, McGregor, who was principally responsible for the destruction of the ammunition tower, was machine gunned as he blew up the tower, then died in the subsequent explosion.

In recognition of their bravery and valor in battle, Lieutenants Forsythe and Stone are awarded the Distinguished Service Order. McGregor posthumously receives the Victoria Cross, Great Britain's highest award for military valor, with Colonel Stone pinning the medal to the saddle cloth of McGregor's horse as was the custom in the 41st Lancers (according to the film).

Cast

- Gary Cooper as Lieutenant Alan McGregor, a highly experienced officer in his mid-thirties, who has spent a long time with the regiment. McGregor, a Canadian, is portrayed as a charming, open character who befriends most officers, but because of disregard for his superiors and habit of speaking his mind is regarded askance by his superiors, who nevertheless respect his military abilities.[6]

- Franchot Tone as Lieutenant John Forsythe, an upper-class cavalryman in his mid-twenties from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. Transferred from the Blues, one of the two regiments at the time the movie was made tasked with guarding the Sovereign, Forsythe is presented as the funny guy of the main characters, and is noteworthy for his Sandhurst style in military exercise, something that earns him countless compliments from his superiors.[6]

- Richard Cromwell as Lieutenant Donald Stone, a recent graduate of Sandhurst and a very young officer. As the son of a colonel with a famous name, he is treated respectfully but becomes frustrated and morose because of personal issues with his father.[6]

- Guy Standing as Colonel Tom Stone, a long-serving colonel who left his home in Britain to serve on the Frontier, and explains to his son in the film that the "service always comes first ... something your mother never understood." He is considered to be a dyed-in-the-wool, by-the-book colonel who suppresses his feelings and never does anything without orders.[6]

- C. Aubrey Smith as Major Hamilton, an old, very experienced major who serves as Colonel Stone's adjutant and Lieutenant Stone's second father and friend. He, along with his chief, planned and coordinated the big assault on Mohammad Khan's fortress.[6]

- Kathleen Burke as Tania Volkanskaya, a beautiful and seductive young Russian woman who is Khan's ally. She is used as Khan's secret ace, who seduces young men when needed to forward Khan's plans. It was she who, with considerable ease, outwitted first Stone and then McGregor and Forsythe.[6]

- Douglass Dumbrille as Mohammed Khan, a well-known, wealthy prince of the region, educated at Oxford and ostensibly a friend of the British. He is also the secret rebel leader who fights for Bengal's independence from the British Crown. He is portrayed as the film's villain and is responsible for the death and torture of many people.[6]

- Colin Tapley as Lieutenant Barrett, a close friend of Lieutenant McGregor who has been ordered to infiltrate Khan's group of bandits and delivers vital information about the rebels' location and movement.[6]

- Lumsden Hare as Major General Woodley, the man in command of the British intelligence service in India. He is disliked by most of the regiment's officers, especially McGregor, because his orders usually involve training exercises in locations where the pig-sticking is good. He thought of and approved the attack on Khan's stronghold.[6]

- J. Carrol Naish as Grand Vizier

- James Dime[7]

Production

Stock crisis

Paramount originally planned to produce the film in 1931 and sent cinematographers Ernest B. Schoedsack and Rex Wimpy to India to film location shots such as a tiger hunt.[8][9] However, much of the film stock deteriorated in the hot sun while on location, so when the film was eventually made, much of the production took place in the hills surrounding Los Angeles, where Northern Paiute people were used as extras.[8][9]

Filming

Among the filming locations were Lone Pine, Calif., Buffalo Flats in Malibu, Calif., the Paramount Ranch in Agoura, Calif., and the Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth, Calif.[8] For the climactic half-hour battle sequence at the end of the film, an elaborate set was built in the Iverson Gorge, part of the Iverson Movie Ranch, to depict Mogala, the mountain stronghold of Mohammed Khan.[8]

Release

Box office

The film was released in American cinemas in January 1935.[6][10] It was a big success at the box office and kicked off a cycle of Imperial adventure tales, including The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), Another Dawn (1937), Gunga Din (1939), The Four Feathers (1939), and The Real Glory (1939).[2] The film had theatrical rentals of about $1 million in the U.S. and Canada,[11] and $1.5 million worldwide.[2] It was the second most popular film at the British box office in 1935–36.[12] The film was successful enough that it led to Gary Cooper being booked to star in a number of films of similar plots that were also set in "exotic" locales, including Beau Geste, The Real Glory, North West Mounted Police and Distant Drums.[13]

Critical reception and influence

Laura Elston from the magazine Canada wrote that The Lives of a Bengal Lancer did "more glory to the British traditions than the British would dare to do for themselves."[2] In response to the film success, Frederick Herron of the Motion Picture Association of America wrote "Hollywood is doing a very good work in selling the British Empire to the world."[2] Writer John Howard Reid noted in his book Award-Winning Films of the 1930s that the film is considered "one of the greatest adventure films of all time" and highly praised Hathaway's work by saying "the film really made his reputation."[14] It also received a praised review in Boys' Life magazine, starting off the review with the words "You will be immensely pleased with The Lives of a Bengal lancer" and went on to compare the style and class of the three main characters to that of The Three Musketeers.[15] The film holds an overall approval rating of 100% on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 9 reviews, with a rating average of 8 out of 10.[16]

Critic Otis Ferguson said he was "taken by the show, imperialism and all." Andre Sennwald of The New York Times said the film "glorified the British Empire better than any film produced in Britain for that purpose." Sennwald added that Paramount's "Kiplingesque" movie "ought to prove a blessing to Downing Street." The film proved so popular in the United States that it spurred a series of imperial films that continued throughout the decade and into the next decade. Frank S. Nugent, also of The New York Times, wrote that "England need have no fears for its empire so long as Hollywood insists upon being the Kipling of the Pacific." Nugent commented that movies such as The Lives of a Bengal Lancer and The Charge of the Light Brigade were far more pro-British than actual British filmmakers would ever dare to be: "In its veneration of British colonial policy, in its respect for the omniscience and high moral purpose of His, or Her, Majesty's diplomatic representatives and in its adulation of the courage, the virtue and the manly beauty of English soldiery abroad, Hollywood yields to no one—not even to the British filmmakers themselves."[17]

In Fascist Italy, Mussolini's motion picture bureau had the movie banned, as well as several other British-themed American movies, including Lloyd's of London and The Charge of the Light Brigade, on the grounds that they were "propaganda". This was seen as an irony in Hollywood, due to the fact that the movies were made to be deliberately apolitical, and were intended to be purely fun escapism.[18]

According to Ivone Kirkpatrick, who met Adolf Hitler at Berchtesgaden in 1937, one of Hitler's favorite films was The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, which he had watched three times.[19] He liked the film because "it depicted a handful of Britons holding a continent in thrall. That was how a superior race must behave and the film was a compulsory viewing for the S.S."[19][20] Also, his valet recalled that Hitler enjoyed the film.[21][22][23] It was one of the eleven US movies that, from 1933 to 1937, were considered "artistically valuable" by the Nazi authorities.[24]

Plot discrepancies

The film The Lives of a Bengal Lancer shares nothing with the source book, except the setting.[25] Reid noted in Award-Winning Films of the 1930s that "none of the characters in the book appear in the screenplay, not even Yeats-Brown himself. The plot of the film is also entirely different.[25]

Home media

The Paramount picture was distributed to home media on VHS on March 1, 1992 and on DVD on May 31, 2005.[9][26] It has since been released in multiple languages and is included in several multi-film collections.[27]

Awards

The film was nominated for the following Academy Awards, winning in one category:[9][28]

| Award | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Best Picture | Louis D. Lighton | Nominated |

| Best Art Direction | Hans Dreier Roland Anderson |

Nominated |

| Best Assistant Director | Clem Beauchamp Paul Wing |

Won |

| Best Directing | Henry Hathaway | Nominated |

| Best Film Editing | Ellsworth Hoagland | Nominated |

| Best Sound Recording | Franklin B. Hansen | Nominated |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | William Slavens McNutt Grover Jones Waldemar Young John L. Balderston Achmed Abdullah |

Nominated |

See also

- The Witching Hour

- The Shepherd of the Hills

- Now and Forever

References

- "AFI|Catalog".

- Welky 2008, pp. 88–89.

- Deis, Robert (January 11, 2015). "The Origin of the Movie Cliché 'We Have Ways of Making You Talk!'". This Day in Quotes. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- Knowles 1999, p. 196.

- "Top 15 Film Misquotes" (October 18, 2007). Listverse. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- "The Lives of a Bengal Lancer" (January 12, 1935). The New York Times. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- Freese, Gene Scott (2014). Hollywood Stunt Performers, 1910s–1970s: A Biographical Dictionary (2nd ed.). McFarland & Company. p. 75. ISBN 978-0786476435.

- Richards 1973, pp. 120–123.

- "Review: The Lives of a Bengal Lancer" (December 31, 1934). Variety. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- "The Lives of a Bengal Lancer". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. p. M-170. ISSN 0042-2738.

- "The Film Business in the United States and Britain during the 1930s" by John Sedgwick and Michael Pokorny, The Economic History ReviewNew Series, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Feb., 2005), p. 97

- Gary Cooper, An Intimate Biography by Hector Arce. Bantam Books, 1980 [ISBN missing][page needed]

- Reid 2004, pp. 118–119.

- Mathiews 1935.

- "The Lives of a Bengal Lancer". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- The American Experience in World War II: The United States and the road to war in Europe by Walter L. Hixson, Taylor & Francis, 2003 p. 24 [ISBN missing]

- Hollywood Goes to War: Films and American Society, 1939–1952 by Colin Shindler p. 2 [ISBN missing]

- Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick, The Inner Circle (London: Macmillan, 1959), p. 97. [ISBN missing]

- David Faber (2009). Munich, 1938: Appeasement and World War II. Simon and Schuster. p. 40. ISBN 143913233X.

- DAlmeida, Fabrice (2008). High Society in the Third Reich. Polity Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0745643113.

- Hamilton, Charles (1984). Leaders & Personalities of the Third Reich, Vol. 1. R. James Bender Publishing. p. 158. ISBN 0912138270.

- Toland, John (1977) [1976]. Adolf Hitler: The Definitive Biography. London: Book Club Associates. p. 411.

- Ursula Saekel: Der US-Film in der Weimarer Republik – ein Medium der "Amerikanisierung"?: Deutsche Filmwirtschaft, Kulturpolitik und mediale Globalisierung im Fokus transatlantischer Interessen. Verlag Schoeningh Ferdinand, 2011, ISBN 3506771744, pp. 169, 255, 258

- Reid 2004, p. 120.

- "The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (VHS)". Amazon. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- "The Oscars 30' Collection – 5 DVD Set". Amazon. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- "The Lives of a Bengal Lancer – Film by Hathaway (1935)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

Sources

- Kirkpatrick, Ivone (1959). The Inner Circle: Memoirs. St. Martin's Press. OCLC 1101750744.

- Knowles, Elizabeth M. (1999). The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860173-9.

- Mathiews, Fraklin K. (1935). "Movies of the Month". Boys' Life. Inkprint Edition. Boys' Life. ISSN 0006-8608.

- Richards, Jeffrey (1973). Visions of Yesterday. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-72681-8.

- Reid, John (2004). Award-Winning Films of the 1930s. Lulu Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4116-1432-1.

- Welky, David (2008). The Moguls and the Dictators: Hollywood and the Coming of World War II. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9044-4.

External links

- The Lives of a Bengal Lancer at Internet Movie Database

- The Lives of a Bengal Lancer at Allmovie

- The Lives of a Bengal Lancer at Turner Classic Movies

- The Lives of a Bengal Lancer at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Lives of a Bengal Lancer at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Lives of a Bengal Lancer VHS trailer on YouTube

- The Lives of a Bengal Lancer scenes on YouTube

На других языках

- [en] The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (film)

[es] The Lives of a Bengal Lancer

The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (en Argentina, Tres lanceros de Bengala; en España, Tres lanceros bengalíes) es una película estadounidense de 1935 dirigida por Henry Hathaway y con Gary Cooper, Franchot Tone, Richard Cromwell, C. Aubrey Smith, Guy Standing y Kathleen Burke como actores principales.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии