fiction.wikisort.org - Movie

The Sting is a 1973 American caper film set in September 1936, involving a complicated plot by two professional grifters (Paul Newman and Robert Redford) to con a mob boss (Robert Shaw).[2] The film was directed by George Roy Hill,[3] who had directed Newman and Redford in the western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Created by screenwriter David S. Ward, the story was inspired by real-life cons perpetrated by brothers Fred and Charley Gondorff and documented by David Maurer in his 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man.

| The Sting | |

|---|---|

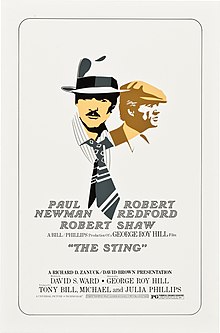

Theatrical release poster (alternate design) | |

| Directed by | George Roy Hill |

| Written by | David S. Ward |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Surtees |

| Edited by | William Reynolds |

| Music by | Marvin Hamlisch |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 129 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $159.6 million[1] |

The title phrase refers to the moment when a con artist finishes the "play" and takes the mark's money. If a con is successful, the mark does not realize he has been cheated until the con men are long gone, if at all. The film is played out in distinct sections with old-fashioned title cards drawn by artist Jaroslav "Jerry" Gebr, the lettering and illustrations rendered in a style reminiscent of the Saturday Evening Post. The film is noted for its anachronistic use of ragtime, particularly the melody "The Entertainer" by Scott Joplin, which was adapted (along with others by Joplin) for the film by Marvin Hamlisch (and a top-ten chart single for Hamlisch when released as a single from the film's soundtrack). The film's success created a resurgence of interest in Joplin's work.[4]

Released on Christmas Day of 1973, The Sting was a massive critical and commercial success and was hugely successful at the 46th Academy Awards, being nominated for ten Oscars and winning seven, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Film Editing and Best Writing (Original Screenplay); Redford was also nominated for Best Actor. The film also rekindled Newman's career after a series of big screen flops. Regarded as having one of the best screenplays ever written, in 2005, The Sting was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry of the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

In 1936, during the Great Depression, Johnny Hooker, a grifter in Joliet, Illinois, cons $11,000 in cash in a pigeon drop from an unsuspecting victim with the aid of his partners Luther Coleman and Joe Erie. Buoyed by the windfall, Luther announces his retirement and advises Hooker to seek out an old friend, Henry Gondorff, in Chicago to learn "the big con". Unfortunately, the reason their victim had so much cash was that he was a numbers racket courier for vicious crime boss Doyle Lonnegan. Corrupt Joliet police Lieutenant William Snyder confronts Hooker, revealing Lonnegan's involvement and demanding part of Hooker's cut. Having already blown his share on a single roulette spin, Hooker pays Snyder in counterfeit bills. Lonnegan's men murder both the courier and Luther, and Hooker flees for his life to Chicago.

Hooker finds Henry Gondorff, a once-great con-man now hiding from the FBI, and asks for his help in taking on the dangerous Lonnegan. Gondorff is initially reluctant, but he relents and recruits a core team of experienced con men to dupe Lonnegan. They decide to resurrect an elaborate obsolete scam known as "the wire", using a larger crew of con artists to create a phony off-track betting parlor. Aboard the opulent 20th Century Limited, Gondorff, posing as boorish Chicago bookie Shaw, buys into Lonnegan's private, high-stakes poker game. He infuriates Lonnegan with obnoxious behavior, then out-cheats him to win $15,000. Hooker, posing as Shaw's disgruntled employee Kelly, is sent to collect the winnings and instead convinces Lonnegan that he wants to take over Shaw's operation. Kelly reveals that he has a partner named Les Harmon (actually con man Kid Twist) in the Chicago Western Union office, who will allow them to win bets on horse races by past-posting.

Meanwhile, Snyder has tracked Hooker to Chicago, but his pursuit is thwarted when he is summoned by undercover FBI agents led by Agent Polk, who orders him to assist in their plan to arrest Gondorff using Hooker. At the same time, Lonnegan has grown frustrated with the inability of his men to find and kill Hooker for the Joliet con. Unaware that Kelly is Hooker, he demands that Salino, his best assassin, be given the job. A mysterious figure with black leather gloves is then seen following and observing Hooker.

Kelly's connection appears effective, as Harmon provides Lonnegan with the winner of one horse race and the trifecta of another. Lonnegan agrees to finance a $500,000 bet at Shaw's parlor to break Shaw and gain revenge. Shortly thereafter, Snyder captures Hooker and brings him before FBI Agent Polk. Polk forces Hooker to betray Gondorff by threatening to incarcerate Luther Coleman's widow.

The night before the sting, Hooker sleeps with a waitress named Loretta. The next morning, he sees Loretta walking toward him. The black-gloved man appears behind Hooker and shoots her dead. The man reveals that he was hired by Gondorff to protect Hooker; Loretta was Lonnegan's hired killer, Loretta Salino, and had not yet killed Hooker because they were seen together.

Armed with Harmon's tip to "place it on Lucky Dan", Lonnegan makes the $500,000 bet at Shaw's parlor on Lucky Dan to win. As the race begins, Harmon arrives and expresses shock at Lonnegan's bet: when he said "place it" he meant, literally, that Lucky Dan would "place" (i.e., finish second). In a panic, Lonnegan rushes to the teller window and demands his money back. A moment later Polk, Lt. Snyder, and a half dozen FBI agents storm the parlor. Polk confronts Gondorff, then tells Hooker he is free to go. Gondorff, reacting to the betrayal, shoots Hooker in the back. Polk then shoots Gondorff and orders Snyder to get the ostensibly respectable Lonnegan away from the crime scene. With Lonnegan and Snyder safely away, Hooker and Gondorff rise amid cheers and laughter. The gunshots were faked; Agent Polk is actually Hickey, a con man, running a con atop Gondorff's con to divert Snyder and ensure Lonnegan abandons the money. As the con men strip the room of its contents, Hooker refuses his share of the money, saying "I'd only blow it", and walks away with Gondorff.

Cast

- Paul Newman as Henry "Shaw" Gondorff

- Robert Redford as Johnny "Kelly" Hooker

- Robert Shaw as Doyle Lonnegan

- Robert Earl Jones as Luther Coleman

- Charles Durning as Lt. William Snyder, Joliet P.D.

- Ray Walston as J.J. Singleton

- Eileen Brennan as Billie

- Harold Gould as Kid Twist

- John Heffernan as Eddie Niles

- Dana Elcar as FBI Agent Polk, aka "Hickey"

- Jack Kehoe as Erie Kid

- Dimitra Arliss as Loretta Salino

- James J. Sloyan as Mottola

- Charles Dierkop as Floyd (Lonnegan's bodyguard)

- Lee Paul as Lonnegan's bodyguard

- Sally Kirkland as Crystal

- Avon Long as Benny Garfield

- Arch Johnson as Combs

- Ed Bakey as Granger

- Brad Sullivan as Cole

- John Quade as Riley

- Larry D. Mann as Clemens (the train conductor)

- Leonard Barr as Burlesque House Comedian

- Paulene Myers as Alva Coleman

- Joe Tornatore as Black Gloved Gunman

- Jack Collins as Duke Boudreau

- Tom Spratley as Curly Jackson

- Kenneth O'Brien as Greer

- Ken Sansom as Western Union Executive

- Ta-Tanisha as Louise Coleman

- William "Billy" Benedict as Jimmy

Production

Writing

Screenwriter David S. Ward has said in an interviews that he was inspired to write The Sting while doing research on pickpockets, saying "Since I had never seen a film about a confidence man before, I said I gotta do this." Daniel Eagan explained: "One key to plots about con men is that film goers want to feel they are in on the trick. They don't have to know how a scheme works, and they don't mind a twist or two, but it's important for the story to feature clearly recognizable 'good' and 'bad' characters." It took a year for Ward to correctly adjust this aspect of the script and to figure out how much information he could hold back from the audience while still making the leads sympathetic. He also imagined an underground brotherhood of thieves who assemble for a big operation and then melt away after the "mark".[5]

Rob Cohen (later director of action films such as The Fast and the Furious) years later told of how he found the script in the slush pile when working as a reader for Mike Medavoy, a future studio head, but then an agent. He wrote in his coverage that it was "the great American screenplay and … will make an award-winning, major-cast, major-director film." Medavoy said that he would try to sell it on that recommendation, promising to fire Cohen if he could not. Universal bought it that afternoon, and Cohen keeps the coverage framed on the wall of his office.[6]

David Maurer sued for plagiarism, claiming the screenplay was based too heavily on his 1940 book The Big Con, about real-life tricksters Fred and Charley Gondorff. Universal settled out of court for $600,000, irking David S. Ward, who resented the presumption of guilt implied by an out-of-court settlement done for business expediency.[7]

Writer/producer Roy Huggins maintained in his Archive of American Television interview that the first half of The Sting plagiarized the famous 1958 Maverick television series episode "Shady Deal at Sunny Acres" starring James Garner and Jack Kelly.

Casting

Ward originally wrote Henry Gondorff as a minor character who was an overweight, past-his-prime slob, but once Paul Newman became associated with the movie, Gondorff was rewritten as a slimmer character and his part was expanded in order to maximize the second partnership of Newman and Redford. Newman had been advised to avoid doing comedies because he didn't have the light touch, but accepted the part to prove that he could handle comedy just as well as drama.[8]

Jack Nicholson was offered the lead role but turned it down.[9]

Newman signed on the film after the producers agreed to give him top billing, $500,000 and a percentage of the profits. Newman needed a hit considering his last five films that he had made prior to The Sting had been box-office disappointments.[10]

In her 1991 autobiography You'll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again, Julia Phillips stated that Hill wanted Richard Boone to play Doyle Lonnegan. Much to her relief, Newman had sent the script to Robert Shaw while shooting The Mackintosh Man in Ireland to ensure his participation in the film. Phillips's book asserts that Shaw was not nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award because he demanded that his name follow those of Newman and Redford before the film's opening title.[11]

Shaw's character's limping in the film was authentic. Shaw had slipped on a wet handball court at the Beverly Hills Hotel a week before filming began and had injured the ligaments in his knee. He wore a leg brace during production which was hidden under the wide 1930s style trousers.[8]

Principal photography

Hill decided that the film would be reminiscent of movies from the 1930s and watched films from that decade for inspiration. While studying '30s gangster films, Hill noticed that most of them rarely had extras. "For instance," said Hill as quoted in Andrew Horton's 1984 book The Films of George Roy Hill, "no extras would be used in street scenes in those films: Jimmy Cagney would be shot down and die in an empty street. So I deliberately avoided using extras."[12]

Along with art director Henry Bumstead and cinematographer Robert L. Surtees, Hill devised a colour scheme of muted browns and maroons for the film and a lighting design that combined old-fashioned 1930s-style lighting with some modern tricks of the trade to get the visual look he wanted. Edith Head designed a wardrobe of snappy period costumes for the cast, and artist Jaroslav Gebr created inter-title cards to be used between each section of the film that were reminiscent of the golden glow of old Saturday Evening Post illustrations, a popular publication of the 1930s.

The movie was filmed on the Universal Studios backlot, with a few small scenes shot in Wheeling, West Virginia, some scenes filmed at the Santa Monica pier's carousel,[13] in Santa Monica, California, and in Chicago at Union Station and the former LaSalle Street Station prior to its demolition.[14][15] Co-producer Tony Bill was an antique car buff who helped round up several period cars to use in The Sting. One of them was his own one-of-a-kind 1935 Pierce-Arrow, which served as Lonnegan's private car.

Reception

Box office

The film was a box-office smash in 1973 and early 1974, taking in over $160 million ($900 million today). As of August 2018, it is the 20th highest-grossing film in the United States adjusted for ticket price inflation.[16]

Critical response

Roger Ebert gave the film a perfect four out of four stars and called it "one of the most stylish movies of the year."[17] Gene Siskel awarded three-and-a-half stars out of four, calling it "a movie movie that has obviously been made with loving care each and every step of the way."[18] Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that the film was "so good-natured, so obviously aware of everything it's up to, even its own picturesque frauds, that I opt to go along with it. One forgives its unrelenting efforts to charm, if only because The Sting itself is a kind of con game, devoid of the poetic aspirations that weighed down Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid."[19] Variety wrote, "George Roy Hill's outstanding direction of David S. Ward's finely-crafted story of multiple deception and surprise ending will delight both mass and class audiences. Extremely handsome production values and a great supporting cast round out the virtues."[20] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called it "an unalloyed delight, the kind of pure entertainment film that's all the more welcome for having become such a rarity."[21] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker was less enthusiastic, writing that the film "is meant to be roguishly charming entertainment, and that's how most of the audience takes it, but I found it visually claustrophobic, and totally mechanical. It creeps cranking on, section after section, and it doesn't have a good spirit." She also noted that "the absence of women really is felt as a lack in this movie."[22] John Simon wrote that The Sting as a comedy-thriller "works endearingly without a hitch".[23]

In 2005, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". The Writers Guild of America ranked the screenplay #39 on its list of 101 Greatest Screenplays ever written.[24] On Rotten Tomatoes, The Sting holds a rating of 92% from 101 reviews, with an average rating of 8.3/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Paul Newman, Robert Redford, and director George Roy Hill prove that charm, humor, and a few slick twists can add up to a great film."[25] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 83 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[26]

Awards and nominations

| Award[27] | Category | Nominees | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[28] | Best Picture | Tony Bill, Julia Phillips and Michael Phillips | Won |

| Best Director | George Roy Hill | Won | |

| Best Actor | Robert Redford | Nominated | |

| Best Original Screenplay | David S. Ward | Won | |

| Best Art Direction | Henry Bumstead and James W. Payne | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Robert Surtees | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Edith Head | Won | |

| Best Film Editing | William Reynolds | Won | |

| Best Scoring: Original Song Score and Adaptation or Scoring: Adaptation | Marvin Hamlisch | Won | |

| Best Sound | Ronald Pierce and Robert R. Bertrand | Nominated | |

| American Cinema Editors Awards | Best Edited Feature Film | William Reynolds | Won |

| David di Donatello Awards | Best Foreign Actor | Robert Redford | Won[lower-alpha 1] |

| Directors Guild of America Awards[29] | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | George Roy Hill | Won |

| Edgar Allan Poe Awards | Best Motion Picture | David S. Ward | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards[30] | Best Screenplay – Motion Picture | Nominated | |

| Golden Screen Awards | Won | ||

| Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Foreign Language Film Director | George Roy Hill | Won |

| National Board of Review Awards[31] | Top Ten Films | Won | |

| Best Film | Won | ||

| National Film Preservation Board | National Film Registry | Inducted | |

| Online Film & Television Association Awards[32] | Hall of Fame – Motion Picture | Won | |

| People's Choice Awards[33] | Favorite Motion Picture | Won | |

| Producers Guild of America Awards[34] | Hall of Fame – Motion Pictures | Tony Bill, Julia Phillips and Michael Phillips | Won |

| Writers Guild of America Awards[35] | Best Drama Written Directly for the Screen | David S. Ward | Nominated |

Soundtrack

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

| The Sting (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | 1973 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 36:59 | |||

| Label | MCA Records | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Marvin Hamlisch chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

The soundtrack album, executive produced by Gil Rodin, included several of Scott Joplin's ragtime compositions, adapted by Marvin Hamlisch.

According to Joplin scholar Edward A. Berlin, ragtime had experienced a revival in the 1970s due to several events: A best-selling recording of Joplin rags on the classical Nonesuch Records label, along with a collection of his music issued by the New York Public Library; the first full staging of Joplin's opera Treemonisha; and, a performance of period orchestrations of Joplin's music by a student ensemble of the New England Conservatory of Music, led by Gunther Schuller. "Inspired by Schuller's recording, [Hill] had Marvin Hamlisch score Joplin's music for the film, thereby bringing Joplin to a mass, popular public."[4]

- "Solace" (Joplin) – orchestral version

- "The Entertainer" (Joplin) – orchestral version

- "The Easy Winners" (Joplin)

- "Hooker's Hooker" (Hamlisch)

- "Luther" – same basic tune as "Solace", re-arranged by Hamlisch as a dirge

- "Pine Apple Rag" / "Gladiolus Rag" medley (Joplin)

- "The Entertainer" (Joplin) – piano version

- "The Glove" (Hamlisch) – a Jazz Age style number; only a short segment was used in the film

- "Little Girl" (Madeline Hyde, Francis Henry) – heard only as a short instrumental segment over a car radio

- "Pine Apple Rag" (Joplin)

- "Merry-Go-Round Music" medley; "Listen to the Mocking Bird", "Darling Nellie Gray", "Turkey in the Straw" (traditional) – "Listen to the Mocking Bird" was the only portion of this track that was actually used in the film, along with a segment of "King Cotton", a Sousa march, a segment of "The Diplomat", another Sousa march, a segment of Sousa's Washington Post March, and a segment of "The Regimental Band", a Charles C. Sweeley march, all of which were not on the album. All six tunes were recorded from the Santa Monica Pier carousel's band organ.

- "Solace" (Joplin) – piano version

- "The Entertainer" / "The Ragtime Dance" medley (Joplin)

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Certifications and sales

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[49] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[50] | Gold | 500,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Stage adaptation

Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis (music and lyrics), writer Bob Martin, and director John Rando created a stage musical version of the movie. The musical premiered at the Paper Mill Playhouse in Millburn, New Jersey on March 29, 2018. The role of Henry Gondorff was played by Harry Connick Jr. with choreography by Warren Carlyle.[51] The stage musical incorporates Scott Joplin's music, including "The Entertainer".[52]

Novelization

The adaptation into a full length novel was written by Robert Weverka. The Sting (1974) Based on the screenplay by David S. Ward.[53]

Home media

The movie was issued on DVD by Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment in 2000. "If Paul Newman really does retire, he can spend his rocking chair years feeling smug about this," enthused OK!. "The story's not the important thing: what makes it are the quirky soundtrack, the card-sharp dialogue and two superduperstars at their superduperstarriest."[54]

A deluxe DVD – The Sting: Special Edition (part of the Universal Legacy Series) – was released in September 2005. Its "making of" featurette, The Art of the Sting, included interviews with cast and crew.

The film was released on Blu-ray in 2012, as part of Universal's 100th anniversary releases.

The Sting was released on Ultra HD Blu-ray on May 18, 2021.[55]

See also

- List of American films of 1973

- List of highest-grossing films in the United States and Canada

- The Sting II

References

- "The Sting". The Numbers. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- Variety film review; December 12, 1973, page 16.

- "The Sting". Turner Classic Movies Database. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- Berlin, Edward A. (1996). "Scott Joplin". Classical Net. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- Eagan, Daniel (2009). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. Bloomsberry. p. 700. ISBN 978-0-8264-2977-3. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- Lussier, Germaine (November 21, 2008). "Screenings: 'The Sting' as part of Paul Newman Retrospective". Times-Herald Record. Middletown, NY. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- "Hollywood Law: Whose Idea Is It, Anyway?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "The Sting - Trivia". IMDb. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- McGilligan, Patrick (November 9, 2015). Jack's Life: A Biography of Jack Nicholson (Updated and Expanded). W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-3933-5097-5.

- J. Quirk, Lawrence (September 16, 2009). Paul Newman: A Life. Taylor Trade Publishing. pp. 212–215. ISBN 978-1-5897-9438-2.

- Phillips, Julia (1991). You'll Never Eat Lunch in this Town Again. Random House. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-3945-7574-2. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- Horton, Andrew (August 31, 2010). The Films of George Roy Hill (revised ed.). McFarland. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-7864-4684-1. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- Blake, Lindsay (January 16, 2014). "Scene It Before: The Santa Monica Looff Hippodrome from 'The Sting'". Los Angeles. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- "LaSalle Street Station". Metra. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- "Movies Filmed in Chicago". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- "All Time Box Office Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 7, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- Ebert, Roger (December 27, 1973). "The Sting". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- Siskel, Gene (December 28, 1973). "A return to the basics called care and skill". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 3.

- Canby, Vincent (December 26, 1973). "Film:1930's Confidence Men Are Heroes of 'Sting'". The New York Times. p. 60. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Murphy, A. D. (December 12, 1973). "The Sting". Variety. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Thomas, Kevin (December 23, 1973). "'The Sting 'Reunites a Winning Combination". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 26.

- Kael, Pauline (December 31, 1973). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. pp. 49–50.

- Simon, John (1982). "Cops, Crooks, and Cryogenics". Reverse Angle: A Decade of American films. Crown Publishers Inc. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-5175-4471-6.

- "101 Greatest Screenplays". Writers Guild of America West. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- "The Sting". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- The Sting Reviews, Metacritic, retrieved June 18, 2022

- "The Sting". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. March 20, 2009. Archived from the original on March 21, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- "The 46th Academy Awards (1974) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- "26th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Winners & Nominees 1974". Golden Globes. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- "1973 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Film Hall of Fame Inductees: Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- "1975 - 1st Annual People's Choice Awards". Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- Madigan, Nick (March 1, 1998). "PGA lauds Daly, Semel with its Golden Laurels". Variety. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- "Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- Lovering, Robert. Marvin Hamlisch – The Sting (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Review at AllMusic. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-6461-1917-5.

- "Top RPM Albums: Issue 5015a". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – Soundtrack / Marvin Hamlisch – The Sting" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Offiziellecharts.de – Soundtrack / Marvin Hamlisch – The Sting" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Norwegiancharts.com – Soundtrack / Marvin Hamlisch – The Sting". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Soundtrack Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Cash Box Top 100 Albums" (PDF). Cashbox. Vol. 35, no. 50. April 27, 1974. p. 41. ISSN 0008-7289. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "The Top 100 Albums of '74" (PDF). RPM. Vol. 22, no. 19. December 28, 1974. p. 15. ISSN 0315-5994. Retrieved May 16, 2022 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- "Top 50 Albums of the Year" (PDF). Cashbox. Vol. 36, no. 31. December 28, 1974. p. 132. ISSN 0008-7289. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Billboard 200 Albums - Year-End". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Top 100 Albums 1974" (PDF). Cashbox. Vol. 36, no. 31. December 28, 1974. p. 36. ISSN 0008-7289. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "British album certifications – The Sting - Ost – Original Soundtrack". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "American album certifications – Marvin Hamlisch – The Sting". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "The Sting". newyorkcitytheatre.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2017.

- Clement, Olivia (February 13, 2018). "Harry Connick Jr. to Star in Broadway-Bound Musical 'The Sting'". Playbill. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018.

- The Sting: Published 1974, Bantam Books (first published January 1st 1973) ISBN 0553082728

- MacDonald, Bruno (May 19, 2000). "Film & Video: DVD sales releases". OK!. No. 213.

- "The Sting 4K Blu-ray". Blu-ray News. March 10, 2021. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

External links

- The Sting at IMDb

- The Sting at the TCM Movie Database

- The Sting at AllMovie

- The Sting at Rotten Tomatoes

На других языках

[de] Der Clou

Der Clou (Originaltitel: The Sting) ist eine Ganoven-Komödie von Regisseur George Roy Hill aus dem Jahr 1973. Sie erzählt die Geschichte zweier Trickbetrüger, die einen raffinierten Plan entwickeln, um sich an einem Mafia-Boss zu rächen, der einen gemeinsamen Freund ermorden ließ. Mittels eines falschen Wettbüros soll der Gangsterchef um einen großen Betrag erleichtert werden. Das Unterfangen wird durch mehrere Auftragskiller und einen korrupten Polizisten erschwert.- [en] The Sting

[it] La stangata

La stangata (The Sting) è un film del 1973 diretto da George Roy Hill, con Paul Newman e Robert Redford, vincitore di 7 premi Oscar tra cui quello al miglior film. Secondo film in cui Paul Newman e Robert Redford recitano insieme, è anche la seconda volta che vengono diretti da George Roy Hill e sempre portando ottimi incassi (il film precedente era stato Butch Cassidy, del 1969).[ru] Афера (фильм, 1973)

«Афера» (англ. The Sting) — художественный фильм режиссёра Джорджа Роя Хилла, вышедший на экраны в 1973 году. Как и в предыдущем фильме Хилла, «Бутч Кэссиди и Санденс Кид», главные роли сыграли Роберт Редфорд и Пол Ньюман.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии