fiction.wikisort.org - Movie

Lawrence of Arabia is a 1962 British epic historical drama film based on the life of T. E. Lawrence and his 1926 book Seven Pillars of Wisdom. It was directed by David Lean and produced by Sam Spiegel, through his British company Horizon Pictures and distributed by Columbia Pictures. The film stars Peter O'Toole as Lawrence with Alec Guinness playing Prince Faisal. The film also stars Jack Hawkins, Anthony Quinn, Omar Sharif, Anthony Quayle, Claude Rains and Arthur Kennedy. The screenplay was written by Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson.

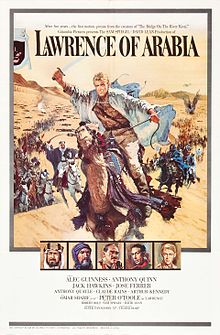

| Lawrence of Arabia | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Howard Terpning | |

| Directed by | David Lean |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T. E. Lawrence |

| Produced by | Sam Spiegel |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Freddie A. Young |

| Edited by | Anne V. Coates |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

Production company | Horizon Pictures[1] |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 227 minutes[2] |

| Country | United Kingdom[3] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million[4] |

| Box office | $70 million[4] |

The film depicts Lawrence's experiences in the Ottoman provinces of Hejaz and Greater Syria during the First World War, in particular his attacks on Aqaba and Damascus and his involvement in the Arab National Council. Its themes include Lawrence's emotional struggles with the violence inherent in war, his identity and his divided allegiance between his native Britain with its army and his new-found comrades within the Arabian desert tribes.

The film was nominated for ten Oscars at the 35th Academy Awards in 1963; it won seven, including Best Picture and Best Director. It also won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama and the BAFTA Awards for Best Film and Outstanding British Film. The dramatic score by Maurice Jarre and the Super Panavision 70 cinematography by Freddie Young also won praise from critics.

Lawrence of Arabia is widely regarded as one of the best films ever made. In 1991, it was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[5][6] In 1998, the American Film Institute placed it fifth on their 100 Years...100 Movies list of the greatest American films and it ranked seventh on their 2007 updated list. In 1999, the British Film Institute named the film the third-greatest British film. In 2004, it was voted the best British film in a Sunday Telegraph poll of Britain's leading film makers.

Plot

The film is presented in two parts, divided by an intermission.

Part I

In 1935, T. E. Lawrence dies in a motorcycle accident. At his memorial service at St Paul's Cathedral, a reporter tries, with little success, to gain insights into the remarkable, enigmatic man from those who knew him.

The story then moves back to the First World War. Lawrence is a misfit British Army lieutenant who is notable for his insolence and education. Over the objections of General Murray, Mr. Dryden of the Arab Bureau sends him to assess the prospects of Prince Faisal in his revolt against the Turks. On the journey, his Bedouin guide, Tafas, is killed by Sherif Ali for drinking from his well without permission. Lawrence later meets Colonel Brighton, who orders him to keep quiet, make his assessment, and leave. Lawrence ignores Brighton's orders when he meets Faisal; his outspokenness piques the prince's interest.

Brighton advises Faisal to retreat after a major defeat, but Lawrence proposes a daring surprise attack on Aqaba. Its capture would provide a port from which the British could offload much-needed supplies. The town is strongly fortified against a naval assault but only lightly defended on the landward side. He convinces Faisal to provide fifty men, led by a pessimistic Sherif Ali. The teenage orphans Daud and Farraj attach themselves to Lawrence as servants. They cross the Nefud Desert, considered impassable even by the Bedouins, and travel day and night on the last stage to reach water. One of Ali's men, Gasim, succumbs to fatigue and falls off his camel unnoticed during the night. When Lawrence discovers him missing, he turns back and rescues Gasim, and Sherif Ali is won over.

Lawrence persuades Auda Abu Tayi, the leader of the powerful local Howeitat tribe, to turn against the Turks. Lawrence's scheme is almost derailed when one of Ali's men kills one of Auda's because of a blood feud. Since retaliation by the Howeitat would shatter the fragile alliance, Lawrence declares that he will execute the murderer himself. Lawrence is then stunned to discover that the culprit is Gasim, the man he risked his own life to save, but Lawrence shoots him anyway.

The next morning, the Arabs overrun the Turkish garrison. Lawrence heads to Cairo to inform Dryden and the new commander, General Allenby, of his victory. While crossing the Sinai Desert, Daud dies when he stumbles into quicksand. Although his report of Aqaba's capture is initially disbelieved, Lawrence is promoted to major and given arms and money for the Arabs. He is deeply disturbed and confesses that he enjoyed executing Gasim, but Allenby brushes aside his qualms. Lawrence asks Allenby whether there is any basis for the Arabs' suspicions that the British have designs on Arabia. When pressed, Allenby states that there is none.

Part II

Lawrence launches a guerrilla war by blowing up the Ottoman railway between Damascus and Medina and harassing the Turks at every turn. An American war correspondent, Jackson Bentley, publicises Lawrence's exploits and makes him famous. On one raid, Farraj is badly injured. Unwilling to leave him to be tortured by the enemy, Lawrence reluctantly shoots him dead and then flees.

When Lawrence scouts the enemy-held city of Deraa with Ali, he is taken, along with several Arab residents, to the Turkish Bey. Lawrence is stripped, ogled, and prodded. Then, for striking out at the Bey, he is severely flogged before he is thrown into the street, where Ali comes to his aid. The experience leaves Lawrence shaken. He returns to British headquarters in Cairo but does not fit in.

A short time later in Jerusalem, General Allenby urges him to support the "big push" on Damascus. Lawrence hesitates to return but finally relents.

Lawrence recruits an army that is motivated more by money than by the Arab cause. They sight a column of retreating Turkish soldiers, who have just massacred the residents of Tafas. One of Lawrence's men is from Tafas and demands, "No prisoners!" When Lawrence hesitates, the man charges the Turks alone and is killed. Lawrence takes up the dead man's battle cry; the result is a slaughter in which Lawrence himself participates, despite Ali's protests. He regrets his actions thereafter.

Lawrence's men take Damascus ahead of Allenby's forces. The Arabs set up a council to administer the city, but the British cut off access to the public utilities, leaving the desert tribesmen to debate how to maintain the occupation. Despite Lawrence's efforts, they bicker constantly, and soon abandon most of the city to the British.

Lawrence is promoted to colonel and immediately ordered back to Britain, as his usefulness to both Faisal and the British is at an end. As he leaves the city, his automobile is passed by a motorcyclist, who leaves a trail of dust in his wake.

Cast

- Peter O'Toole as T. E. Lawrence. Albert Finney was a virtual unknown at the time but he was Lean's first choice to play Lawrence. Finney was cast and began principal photography but was fired after two days for reasons that are still unclear. Marlon Brando was also offered the part and Anthony Perkins and Montgomery Clift were briefly considered before O'Toole was cast.[7] Alec Guinness had played Lawrence in the play Ross and was briefly considered for the part but David Lean and Sam Spiegel thought him too old. Lean had seen O'Toole in The Day They Robbed the Bank of England and was bowled over by his screen test, proclaiming, "This is Lawrence!" Spiegel disliked Montgomery Clift, having worked with him on Suddenly, Last Summer. Spiegel eventually acceded to Lean's choice, though he disliked O'Toole after seeing him in an unsuccessful screen test for Suddenly, Last Summer.[8] Pictures of Lawrence suggest also that O'Toole bore some resemblance to him, though at 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m) tall O'Toole was significantly taller than Lawrence.[9] O'Toole's looks prompted a different reaction from Noël Coward, who quipped after seeing the première of the film, "If you had been any prettier, the film would have been called Florence of Arabia".[10]

- Alec Guinness as Prince Faisal. Faisal was originally to be portrayed by Laurence Olivier. Guinness performed in other David Lean films and he got the part when Olivier dropped out. Guinness was made up to look as much like the real Faisal as possible; he recorded in his diaries that, while shooting in Jordan, he met several people who had known Faisal who actually mistook him for the late prince. Guinness said in interviews that he developed his Arab accent from a conversation that he had with Omar Sharif.

- Anthony Quinn as Auda abu Tayi. Quinn got very much into his role; he spent hours applying his own makeup, using a photograph of the real Auda to make himself look as much like him as he could. One anecdote has Quinn arriving on-set for the first time in full costume, whereupon Lean mistook him for a native and asked his assistant to ring Quinn and notify him that they were replacing him with the new arrival.

- Jack Hawkins as General Edmund Allenby. Sam Spiegel pushed Lean to cast Cary Grant or Laurence Olivier (who was engaged at the Chichester Festival Theatre and declined). Lean convinced him to choose Hawkins because of his work for them on The Bridge on the River Kwai. Hawkins shaved his head for the role and reportedly clashed with Lean several times during filming. Guinness recounted that Hawkins was reprimanded by Lean for celebrating the end of a day's filming with an impromptu dance. Hawkins became close friends with O'Toole during filming, and the two often improvised dialogue during takes to Lean's dismay.

- Omar Sharif as Sherif Ali ibn el Kharish. The role was offered to many actors before Sharif was cast. Horst Buchholz was the first choice but had already signed on for the film One, Two, Three. Alain Delon had a successful screen test but ultimately declined because of the brown contact lenses he would have had to wear. Maurice Ronet and Dilip Kumar were also considered.[11] Sharif, who was already a major star in the Middle East, was originally cast as Lawrence's guide Tafas but when the other actors proved unsuitable, Sharif was shifted to the part of Ali. A combination of numerous Arab leaders, particularly Sharif Nassir—Faisal's cousin, who led the Harith forces involved in the attack on Aqaba, this character was created largely because Lawrence did not serve with any one Arab leader (aside from Auda) throughout the majority of the war; most such leaders were amalgamated in Ali's character.

- José Ferrer as the Turkish Bey. Ferrer was initially unsatisfied with the small size of his part and accepted the role only on the condition of being paid $25,000 (more than O'Toole and Sharif combined) plus a Porsche.[12] Afterwards Ferrer considered this his best film performance, saying in an interview: "If I was to be judged by any one film performance, it would be my five minutes in Lawrence". Peter O'Toole once said that he learned more about screen acting from Ferrer than he could in any acting class. According to Lawrence in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, this was General Hajim Bey (in Turkish, Hacim Muhiddin Bey), though the film doesn't name him. Some biographers (Jeremy Wilson, John Mack) argue that Lawrence's account is to be believed; others including Michael Asher and Lawrence James argue that contemporary evidence suggests that Lawrence never went to Deraa at this time and that the story is invented.

- Anthony Quayle as Colonel Harry Brighton. Quayle, a veteran of military roles, was cast after Jack Hawkins, the original choice, was shifted to the part of Allenby. Quayle and Lean argued over how to portray the character, with Lean feeling Brighton to be an honourable character, while Quayle thought him an idiot. In essence a composite of all of the British officers who served in the Middle East with Lawrence, most notably Lt. Col. S. F. Newcombe (in Michael Wilson's original script, the character was named Colonel Newcombe, before Robert Bolt changed it). Newcombe, like Brighton in the film, was Lawrence's predecessor as liaison to the Arab Revolt; he and many of his men were captured by the Turks in 1916 but he escaped. Brighton was created to represent how ordinary British soldiers would feel about a man like Lawrence: impressed by his accomplishments but repulsed by his affected manner.

- Claude Rains as Mr. Dryden. Like Sherif Ali and Colonel Brighton, Dryden was an amalgamation of several historical figures, primarily Ronald Storrs, a member of the Arab Bureau but also David Hogarth, an archaeologist friend of Lawrence; Henry McMahon, the High Commissioner of Egypt who negotiated the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence which began the Arab Revolt and Mark Sykes, who helped draw up the Sykes–Picot Agreement which partitioned the post-war Middle East. Robert Bolt stated that the character was created to "represent the civilian and political wing of British interests, to balance Allenby's military objectives".[13]

- Arthur Kennedy as Jackson Bentley. In the early days of the production, when the Bentley character had a more prominent role in the film, Kirk Douglas was considered for the part; Douglas expressed interest but demanded a star salary and the highest billing after O'Toole and thus was turned down by Spiegel. Later, Edmond O'Brien was cast in the part.[14] O'Brien filmed the Jerusalem scene and (according to Omar Sharif) Bentley's political discussion with Ali but he suffered a heart attack on location and had to be replaced at the last moment by Kennedy, who was recommended to Lean by Anthony Quinn.[15] The character was based on famed American journalist Lowell Thomas, whose reports helped make Lawrence famous. Thomas was a young man at the time who spent only weeks at most with Lawrence in the field, unlike Bentley, who is a middle-aged man present for all of Lawrence's later campaigns. Bentley was the narrator in Wilson's original script but Bolt reduced his role significantly in the final treatment.

- Donald Wolfit as General Archibald Murray. He releases Lawrence to Mr. Dryden. Calls the British occupying Arabia "a sideshow of a sideshow."

- I. S. Johar as Gasim. Johar was a well-known Indian actor who occasionally appeared in international productions.

- Gamil Ratib as Majid. Ratib was a veteran Egyptian actor. His English was not considered good enough, so he was dubbed by Robert Rietti (uncredited)[citation needed] in the final edit.

- Michel Ray as Farraj. At the time, Ray was an up-and-coming Anglo-Brazilian actor who had appeared in several films, including Irving Rapper's The Brave One and Anthony Mann's The Tin Star.

- John Dimech as Daud

- Zia Mohyeddin as Tafas. Mohyeddin, one of Pakistan's best-known actors, played a character based on his actual guide Sheikh Obeid el-Rashid of the Hazimi branch of the Beni Salem, whom Lawrence referred to as Tafas several times in Seven Pillars.

- Howard Marion-Crawford as the medical officer. He was cast at the last minute during the filming of the Damascus scenes in Seville. The character was based on an officer mentioned in an incident in Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Lawrence's meeting the officer again while in British uniform was an invention of the script.

- Jack Gwillim as the club secretary. Gwillim was recommended to Lean for the film by close friend Quayle.

- Hugh Miller as the RAMC colonel. He worked on several of Lean's films as a dialogue coach and was one of several members of the film crew to be given bit parts (see below).

- Peter Burton as a Damascus sheik (uncredited)

- Kenneth Fortescue as Allenby's aide (uncredited)[16]

- Harry Fowler as Corporal William Potter (uncredited)[17]

- Jack Hedley as a reporter (uncredited)

- Ian MacNaughton as Corporal Michael George Hartley, Lawrence's companion in O'Toole's first scene (uncredited)

- Henry Oscar as Silliam, Faisal's servant (uncredited)

- Norman Rossington as Corporal Jenkins (uncredited)[16]

- John Ruddock as Elder Harith (uncredited)[16]

- Fernando Sancho as the Turkish sergeant (uncredited)

- Stuart Saunders as the regimental sergeant major (uncredited)

- Bryan Pringle as the driver of the car which takes Lawrence away at the end of the film (uncredited)

The crew consisted of over 200 people, with the cast and extras included over 1,000 people worked on the film.[18] Members of the crew portrayed minor characters. First assistant director Roy Stevens played the truck driver who transports Lawrence and Farraj to the Cairo HQ at the end of Act I; the Sergeant who stops Lawrence and Farraj ("Where do you think you're going to, Mustapha?") is construction assistant Fred Bennett and screenwriter Robert Bolt has a wordless cameo as one of the officers watching Allenby and Lawrence confer in the courtyard (he is smoking a pipe).[19] Steve Birtles, the film's gaffer, plays the motorcyclist at the Suez Canal; Lean is rumoured to be the voice shouting "Who are you?" Continuity supervisor Barbara Cole appears as one of the nurses in the Damascus hospital scene.[citation needed]

Historical accuracy

Most of the film's characters are based on people to varying degrees. Some scenes were heavily fictionalised, such as the Battle of Aqaba and those dealing with the Arab Council were inaccurate since the council remained more or less in power in Syria until France deposed Faisal in 1920. Little background is provided on the history of the region, the First World War and the Arab Revolt, probably because of Bolt's increased focus on Lawrence (Wilson's draft script had a broader, more politicised version of events). The second half of the film presents a fictional desertion of Lawrence's Arab army, almost to a man, as he moved farther north. The film's timeline is frequently questionable on the Arab Revolt and First World War, as well as the geography of the Hejaz region. Bentley's meeting with Faisal is in late 1917, after the fall of Aqaba and mentions that the United States has not yet entered the war but the US had been in the war since April. Lawrence's involvement in the Arab Revolt prior to the attack on Aqaba is absent, such as his involvement in the seizures of Yenbo and Wejh. The rescue and the execution of Gasim are based on two incidents, which were conflated for dramatic reasons.

The film shows Lawrence representing the Allied cause in the Hejaz almost alone, with Colonel Brighton (Anthony Quayle) the only British officer there to assist him. In fact, there were numerous British officers such as colonels Cyril Wilson, Stewart Newcombe, and Pierce C. Joyce, all of whom arrived before Lawrence began serving in Arabia.[20] There was a French military mission led by Colonel Édouard Brémond serving in the Hejaz but it is not mentioned in the film.[21] The film shows Lawrence as the originator of the attacks on the Hejaz railroad. The first attacks began in early January 1917 led by officers such as Newcombe.[22] The first successful attack on the Hejaz railroad with a locomotive-destroying "Garland mine" was led by Major Herbert Garland in February 1917, a month before Lawrence's first attack.[23]

The film shows the Hashemite forces consisting of Bedouin guerrillas but the core of the Hashemite force was the regular Arab Army recruited from Ottoman Arab prisoners of war, who wore British-style uniforms with keffiyehs and fought in conventional battles.[24] The film makes no mention of the Sharifian Army and leaves the viewer with the impression that the Hashemite forces were composed exclusively of Bedouin irregulars.

Representation of Lawrence

Many complaints about the film's accuracy concern the characterisation of Lawrence. The perceived problems with the portrayal begin with the differences in his physical appearance; the 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) Peter O'Toole was almost 9 in (230 mm) taller than the 5 ft 5 in (1.65 m) Lawrence.[25] His behaviour, however, has caused much more debate.

The screenwriters depict Lawrence as an egotist. It is not clear to what degree Lawrence sought or shunned attention, as evidenced by his use of various assumed names after the war. Even during the war, Lowell Thomas wrote in With Lawrence in Arabia that he could take pictures of him only by tricking him but Lawrence later agreed to pose for several photos for Thomas's stage show. Thomas's famous comment that Lawrence "had a genius for backing into the limelight" can be taken to suggest that his extraordinary actions prevented him from being as private as he would have liked or it can be taken to suggest that Lawrence made a pretence of avoiding the limelight but subtly placed himself at centre stage. Others point to Lawrence's writings to support the argument that he was egotistical.

Lawrence's sexual orientation remains a controversial topic among historians. Bolt's primary source was ostensibly Seven Pillars but the film's portrayal seems informed by Richard Aldington's Biographical Inquiry (1955), which posited Lawrence as a "pathological liar and exhibitionist" as well as a homosexual. That is opposed to his portrayal in Ross as "physically and spiritually recluse".[26] Historians like B. H. Liddell Hart disputed the film's depiction of Lawrence as an active participant in the attack and slaughter of the retreating Turkish columns who had committed the Tafas massacre but most current biographers accept the film's portrayal as reasonably accurate.

The film shows that Lawrence spoke and read Arabic, could quote the Quran and was reasonably knowledgeable about the region. It barely mentions his archaeological travels from 1911 to 1914 in Syria and Arabia and ignores his espionage work, including a pre-war topographical survey of the Sinai Peninsula and his attempts to negotiate the release of British prisoners at Kut, Mesopotamia, in 1916. Lawrence is made aware of the Sykes–Picot Agreement very late in the story and is shown to be appalled by it but he may well have known about it much earlier while he fought with the Arabs.[27]

Lawrence's biographers have a mixed reaction towards the film. The authorised biographer Jeremy Wilson noted that the film has "undoubtedly influenced the perceptions of some subsequent biographers", such as the depiction of the film's Ali being real, rather than a composite character and also the highlighting of the Deraa incident.[28] The film's historical inaccuracies, in Wilson's view, are more questionable than should be allowed under normal dramatic licence. Liddell Hart criticised the film and engaged Bolt in a lengthy correspondence over its portrayal of Lawrence.[29]

Representation of other characters

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2019) |

The film portrays Allenby as cynical and manipulative, with a superior attitude to Lawrence but there is much evidence that Allenby and Lawrence liked and respected each other. Lawrence once said that Allenby was "an admiration of mine" and later that he was "physically large and confident and morally so great that the comprehension of our littleness came slow to him".[30][31] The fictional Allenby's words at Lawrence's funeral in the film stand in contrast to the real Allenby's remarks upon Lawrence's death,

I have lost a good friend and a valued comrade. Lawrence was under my command, but, after acquainting him with my strategical plan, I gave him a free hand. His co-operation was marked by the utmost loyalty, and I never had anything but praise for his work, which, indeed, was invaluable throughout the campaign."[32]

Allenby also spoke highly of him numerous times and, much to Lawrence's delight, publicly endorsed the accuracy of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Although Allenby manipulated Lawrence during the war, their relationship lasted for years after its end, indicating that in real life, they were friendly, if not close. The Allenby family was particularly upset by the Damascus scenes in which Allenby coldly allows the town to fall into chaos as the Arab Council collapses.[33]

Murray was initially sceptical of the Arab Revolt's potential but thought highly of Lawrence's abilities as an intelligence officer. It was largely through Lawrence's persuasion that Murray came to support the revolt. The intense dislike shown toward Lawrence in the film is the opposite of Murray's real feelings but Lawrence seemed not to hold Murray in any high regard.

The depiction of Auda abu Tayi as a man interested only in loot and money is also at odds with the historical record. Although Auda at first joined the revolt for monetary reasons, he quickly became a steadfast supporter of Arab independence, notably after Aqaba's capture. Despite repeated bribery attempts by the Turks, he happily pocketed their money but remained loyal to the revolt and went so far as to knock out his false teeth, which were Turkish-made. He was present with Lawrence from the beginning of the Aqaba expedition and in fact helped to plan it, along with Lawrence and Prince Faisal. Faisal was far from being the middle-aged man depicted since he was in his early thirties at the time of the revolt. Faisal and Lawrence respected each other's capabilities and intelligence and worked well together.[34]

The reactions of those who knew Lawrence and the other characters say much about the film's veracity. The most vehement critic of its accuracy was Professor A. W. Lawrence, the protagonist's younger brother and literary executor, who had sold the rights to Seven Pillars of Wisdom to Spiegel for £25,000 and went on a campaign in the United States and Britain to denounce the film. He famously said, "I should not have recognised my own brother". In one pointed talk show appearance, he remarked that he had found the film "pretentious and false" and went on to say that his brother was "one of the nicest, kindest and most exhilarating people I've known. He often appeared cheerful when he was unhappy". Later, he said to The New York Times, "[The film is] a psychological recipe. Take an ounce of narcissism, a pound of exhibitionism, a pint of sadism, a gallon of blood-lust and a sprinkle of other aberrations and stir well." Lowell Thomas was also critical of the portrayal of Lawrence and of most of the film's characters and believed that the train attack scenes were the only reasonably accurate aspect of the film. Criticisms were not restricted to Lawrence. Allenby's family lodged a formal complaint against Columbia about his portrayal. Descendants of Auda abu Tayi and the real Sherif Ali, Sharif Nassir, went further by suing Columbia although the film's Ali was a fictional composite character. The Auda case went on for almost 10 years before it was dropped.[35]

The film has its defenders. Biographer Michael Korda, the author of Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia, offers a different opinion. The film is neither "the full story of Lawrence's life or a completely accurate account of the two years he spent fighting with the Arabs". Korda said that criticising its inaccuracy "misses the point". "The object was to produce, not a faithful docudrama that would educate the audience, but a hit picture".[36] Stephen E. Tabachnick goes further than Korda by arguing that the film's portrayal of Lawrence is "appropriate and true to the text of Seven Pillars of Wisdom".[37] A British historian of the Arab Revolt, David Murphy, wrote that although the film was flawed by various inaccuracies and omissions, "it was a truly epic movie and is rightly seen as a classic".[38]

Production

Pre-production

Previous films about T. E. Lawrence had been planned but had not been made. In the 1940s, Alexander Korda was interested in filming The Seven Pillars of Wisdom with Laurence Olivier, Leslie Howard, or Robert Donat as Lawrence, but had to pull out owing to financial difficulties. David Lean had been approached to direct a 1952 version for the Rank Organisation, but the project fell through.[39] At the same time as pre-production of the film, Terence Rattigan was developing his play Ross which centred primarily on Lawrence's alleged homosexuality. Ross had begun as a screenplay, but was re-written for the stage when the film project fell through. Sam Spiegel grew furious and attempted to have the play suppressed, which helped to gain publicity for the film.[40] Dirk Bogarde had accepted the role in Ross; he described the cancellation of the project as "my bitterest disappointment". Alec Guinness played the role on stage.[41]

Lean and Sam Spiegel had worked together on The Bridge on the River Kwai and decided to collaborate again. For a time, Lean was interested in a biopic of Gandhi, with Alec Guinness to play the title role and Emeric Pressburger writing the screenplay. He eventually lost interest in the project, despite extensive pre-production work, including location scouting in India and a meeting with Jawaharlal Nehru.[42] Lean then returned his attention to T. E. Lawrence. Columbia Pictures had an interest in a Lawrence project dating back to the early 50s, and the project got underway when Spiegel convinced a reluctant A. W. Lawrence to sell the rights to Seven Pillars of Wisdom for £22,500.[43]

Michael Wilson wrote the original draft of the screenplay. Lean was dissatisfied with Wilson's work, primarily because his treatment focused on the historical and political aspects of the Arab Revolt. Lean hired Robert Bolt to re-write the script to make it a character study of Lawrence. Many of the characters and scenes are Wilson's invention but virtually all of the dialogue in the finished film was written by Bolt.[44]

Lean reportedly watched John Ford's film The Searchers (1956) to help him develop ideas as to how to shoot the film. Several scenes directly recall Ford's film, most notably Ali's entrance at the well and the composition of many of the desert scenes and the dramatic exit from Wadi Rum. Lean biographer Kevin Brownlow notes a physical similarity between Wadi Rum and Ford's Monument Valley.[45]

In an interview with The Washington Post in 1989, Lean said that Lawrence and Ali were written as being in a gay relationship together. When asked about whether the film was "pervasively homoerotic", Lean responded: "Yes. Of course it is. Throughout. I'll never forget standing there in the desert once, with some of these tough Arab buggers, some of the toughest we had, and I suddenly thought, 'He's making eyes at me!' And he was! So it does pervade it, the whole story, and certainly Lawrence was very if not entirely homosexual. We thought we were being very daring at the time: Lawrence and Omar, Lawrence and the Arab boys."[46] Lean also compared Ali and Lawrence's romance in the film to the relationship of the two main characters in his 1945 film Brief Encounter.[47]

Filming

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

The film was made by Horizon Pictures and distributed by Columbia Pictures. Principal photography began on 15 May 1961 and ended on 21 September 1962.[48] The desert scenes were shot in Jordan and Morocco and Almería and Doñana in Spain. It was originally to be filmed entirely in Jordan; the government of King Hussein was extremely helpful in providing logistical assistance, location scouting, transport and extras. Hussein visited the set several times during production and maintained cordial relationships with cast and crew. The only tension occurred when Jordanian officials learned that English actor Henry Oscar did not speak Arabic but would be filmed reciting the Quran. Permission was granted only on condition that an imam be present to ensure that there were no misquotations.

Lean planned to film in Aqaba and the archaeological site at Petra, which Lawrence had been fond of as a place of study. The production had to be moved to Spain due to cost and outbreaks of illness among the cast and crew before these scenes could be shot. The attack on Aqaba was reconstructed in a dried river bed in Playa del Algarrobico, southern Spain (at 37°1′25″N 1°52′53″W); it consisted of more than 300 buildings and was meticulously based on the town's appearance in 1917. The execution of Gasim, the train attacks, and Deraa exteriors were filmed in the Almería region, with some of the filming being delayed because of a flash flood. The Sierra Nevada mountains filled in for Azrak, Lawrence's winter quarters. The city of Seville was used to represent Cairo, Jerusalem and Damascus, with the appearance of Casa de Pilatos, the Alcázar of Seville and the Plaza de España. All of the interiors were shot in Spain, including Lawrence's first meeting with Faisal and the scene in Auda's tent. The Tafas massacre was filmed in Ouarzazate, Morocco, with Moroccan soldiers substituting for the Turkish army; Lean could not film as much as he wanted because the soldiers were uncooperative and impatient.[49]

The film's production was frequently delayed because shooting commenced without a finished script. Wilson quit early in the production and the playwright Beverley Cross worked on the script in the interim before Bolt took over, although none of Cross's material made it to the film. A further mishap occurred when Bolt was arrested for taking part in an anti-nuclear weapons demonstration and Spiegel had to persuade him to sign a recognizance of good behaviour to be released from jail and continue working on the script.

O'Toole was not used to riding camels and found the saddle to be uncomfortable. During a break in filming, he bought a piece of foam rubber at a market and added it to his saddle. Many of the extras copied the idea and sheets of the foam can be seen on many of the horse and camel saddles. The Bedouin nicknamed O'Toole "'Ab al-'Isfanjah" (أب الإسفنجة), meaning "Father of the Sponge".[50] During the filming of the Aqaba scene, O'Toole was nearly killed when he fell from his camel but it fortunately stood over him, preventing the horses of the extras from trampling him. Coincidentally, a very similar mishap befell the real Lawrence at the Battle of Abu El Lissal in 1917. Jordan banned the film for what was felt to be a disrespectful portrayal of Arab culture.[9] Egypt, Omar Sharif's home country, was the only Arab nation to give the film a wide release, where it became a success through the endorsement of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who appreciated the film's depiction of Arab nationalism.

Super Panavision technology was used to shoot the film, meaning that spherical lenses were used instead of anamorphic ones, and the image was exposed on a 65 mm negative, then printed onto a 70 mm positive to leave room for the soundtracks. Rapid cutting was more disturbing on the wide screen, so film makers had to apply longer and more fluid takes. Shooting such a wide ratio produced some unwanted effects during projection, such as a peculiar "flutter" effect, a blurring of certain parts of the image. To avoid the problem, the director often had to modify blocking, giving the actor a more diagonal movement, where the flutter was less likely to occur.[51] David Lean was asked whether he could handle CinemaScope: "If one had an eye for composition, there would be no problem."[52] O'Toole did not share Lawrence's love of the desert and stated in an interview "I loathe it".[53]

Music

The film score was composed by Maurice Jarre, little known at the time and selected only after both William Walton and Malcolm Arnold had proved unavailable. Jarre was given just six weeks to compose two hours of orchestral music for Lawrence.[54] The score was performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Sir Adrian Boult is listed as the conductor of the score in the film's credits, but he could not conduct most of the score, due in part to his failure to adapt to the intricate timings of each cue, and Jarre replaced him as the conductor. The score went on to garner Jarre his first Academy Award for Music Score—Substantially Original[55] and is now considered one of the greatest scores of all time, ranking number three on the American Film Institute's top twenty-five film scores.[56]

Producer Sam Spiegel wanted to create a score with two themes to show the 'Eastern' and British side for the film. It was intended for Soviet composer Aram Khachaturian to create one half and British composer Benjamin Britten to write the other.[57]

The original soundtrack recording was originally released on Colpix Records, the records division of Columbia Pictures, in 1962. A remastered edition appeared on Castle Music, a division of the Sanctuary Records Group, on 28 August 2006.

Kenneth Alford's march The Voice of the Guns (1917) is prominently featured on the soundtrack. One of Alford's other pieces, the Colonel Bogey March, was the musical theme for Lean's previous film The Bridge on the River Kwai.

A complete recording of the score was not heard until 2010 when Tadlow Music produced a CD of the music, with Nic Raine conducting the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra from scores reconstructed by Leigh Phillips.

Release

Theatrical run

The film premiered at the Odeon Leicester Square in London on 10 December 1962 (Royal Premiere) and was released in the United States on 16 December 1962.

The original release ran for about 222 minutes (plus overture, intermission, and exit music). A post-premiere memo (13 December 1962) noted that the film was 24,987.5 feet (7,616.2 m) of 70 mm film, or 19,990 feet (6,090 m) of 35 mm film. With 90 feet (27 m) of 35 mm film projected every minute, this corresponds to exactly 222.11 minutes. Richard May, VP Film Preservation at Warner Bros., sent an email to Robert Morris, co-author of a book on Lawrence of Arabia, in which he noted that Gone With the Wind was never edited after its premiere and is 19,884 feet (6,061 m) of 35 mm film (without leaders, overture, intermission, entr'acte, or walkout music), corresponding to 220.93 min. Thus, Lawrence of Arabia is slightly more than 1 minute longer than Gone With the Wind and is, therefore, the longest movie ever to win a Best Picture Oscar.

In January 1963, Lawrence was released in a version edited by 20 minutes; when it was re-released in 1971, an even shorter cut of 187 minutes was presented. The first round of cuts was made at the direction and even insistence of David Lean, to assuage criticisms of the film's length and increase the number of showings per day; however, during the 1989 restoration, he passed blame for the cuts onto deceased producer Sam Spiegel.[58] In addition, a 1966 print was used for initial television and video releases which accidentally altered a few scenes by reversing the image.[59]

The film was screened out of competition at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival[60] and at the 2012 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival.[61]

Lawrence of Arabia was re-released theatrically in 2002 to celebrate the film's fortieth anniversary.[62]

Restored director's cut

A restored version was undertaken by Robert A. Harris and Jim Painten under the supervision of David Lean. It was released in 1989 with a 216-minute length (plus overture, intermission and exit music). Most of the cut scenes were dialogue sequences, particularly those involving General Allenby and his staff. Two scenes were excised—Brighton's briefing of Allenby in Jerusalem before the Deraa scene and the British staff meeting in the field tent—and the Allenby-briefing scene has still not been entirely restored. Much of the missing dialogue involves Lawrence's writing of poetry and verse, alluded to by Allenby in particular, saying "the last poetry general we had was Wellington". The opening of Act II existed in only fragmented form, where Faisal is interviewed by Bentley, as well as the later scene in Jerusalem where Allenby convinces Lawrence not to resign. Both scenes were restored to the 1989 re-release. Some of the more graphic shots of the Tafas massacre scene were also restored, such as the lengthy panning shot of the corpses in Tafas and Lawrence shooting a surrendering Turkish soldier.

Most of the missing footage is of minimal import, supplementing existing scenes. One scene is an extended version of the Deraa torture sequence, which makes Lawrence's punishment more overt. Other scripted scenes exist, including a conversation between Auda and Lawrence immediately after the fall of Aqaba, a brief scene of Turkish officers noting the extent of Lawrence's campaign and the battle of Petra (later reworked into the first train attack) but these scenes were probably not filmed. Living actors dubbed their dialogue and Jack Hawkins's dialogue was dubbed by Charles Gray, who had provided Hawkins' voice for several films after Hawkins developed throat cancer in the late 1960s. A full list of cuts can be found at the IMDb.[63] Reasons for the cuts of various scenes can be found in Lean's notes to Sam Spiegel, Robert Bolt and Anne V. Coates.[64] The film runs 227 minutes in the most recent director's cut available on Blu-ray Disc and DVD.[2]

Television and home media

On the evenings of 28 and 29 January 1973, ABC broadcast the film over two evenings, due to the film's length.[65] On 21 August 1977, ABC re-broadcast it, in one 8 p.m. to midnight showing.[66]

Lawrence of Arabia has been released in five different DVD editions, including an initial release as a two-disc set (2001),[67] followed by a shorter single disc edition (2002),[68] a high resolution version of the director's cut with restored scenes (2003) issued as part of the Superbit series, as part of the Columbia Best Pictures collection (2008), and in a fully restored special edition of the director's cut (2008).[69]

Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg helped restore a version of the film for a DVD release in 2000.[70]

New restoration, Blu-ray, and theatrical re-release

An 8K scan/4K intermediate digital restoration was made for Blu-ray and theatrical re-release[71] during 2012 by Sony Pictures to celebrate the film's 50th anniversary.[72] The Blu-ray edition of the film was released in the United Kingdom on 10 September 2012 and in the United States on 13 November 2012.[73] The film received a one-day theatrical release on 4 October 2012 and a two-day release in Canada on 11 and 15 November 2012, and it was re-released in the United Kingdom on 23 November 2012.

According to Grover Crisp, executive VP of restoration at Sony Pictures, the new 8K scan has such high resolution that it showed a series of fine concentric lines in a pattern "reminiscent of a fingerprint" near the top of the frame. This was caused by the film emulsion melting and cracking in the desert heat during production. Sony had to hire a third party to minimise or eliminate the rippling artefacts in the new restored version.[71] The digital restoration was done by Sony Colorworks DI, Prasad Studios, and MTI Film.[74]

A 4K digitally restored version of the film was screened at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival,[75][76] at the 2012 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival,[61] at the V Janela Internacional de Cinema[77] in Recife, Brazil, and at the 2013 Cinequest Film & Creativity Festival in San Jose, California.[78]

In 2020, Sony Pictures included the film on a multi-film 4K UHD Blu-Ray release, The Columbia Classics 4K UltraHD Collection, including other historically significant films from their library such as Dr. Strangelove and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. The film was later released in an individual two-disc steelbook set by Kino Lorber, with both including a substantial, mostly overlapping collection of special features.[79]

Reception

Upon release, Lawrence of Arabia was a huge financial success and was widely acclaimed by critics and audiences alike. The film's visuals, score, screenplay and performance by Peter O'Toole have all been common points of praise; the film is widely considered a masterpiece of world cinema and one of the greatest films ever made. Its visual style has influenced many directors, including George Lucas, Sam Peckinpah, Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, Ridley Scott, Brian De Palma, Oliver Stone and Steven Spielberg, who called the film a "miracle".[80]

The American Film Institute ranked Lawrence of Arabia 5th in its original and 7th in its updated 100 Years...100 Movies lists and first in its list of the greatest American films of the "epic" genre.[81] In 1991, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. In 1999, the film placed third in the British Film Institute's poll of the best British films of the 20th century and in 2001 the magazine Total Film called it "as shockingly beautiful and hugely intelligent as any film ever made" and "faultless".[82] It was ranked in the top ten films of all time in the 2002 Sight & Sound directors' poll.[83] In 2004, it was voted the best British film of all time by over 200 respondents in The Sunday Telegraph poll of Britain's leading film makers.[84] O'Toole's performance is often considered one of the greatest in all of cinema, topping lists from Entertainment Weekly and Premiere. T. E. Lawrence, portrayed by O'Toole, was selected as the tenth-greatest hero in cinema history by the American Film Institute.[85]

Lawrence of Arabia is currently one of the highest-rated films on Metacritic; it holds a perfect 100/100 rating, indicating "universal acclaim", based on eight reviews.[86] It has a 94% "Certified Fresh" approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 125 reviews with an average rating of 9.30/10 from critics with the consensus stating, "The epic of all epics, Lawrence of Arabia cements director David Lean's status in the film-making pantheon with nearly four hours of grand scope, brilliant performances, and beautiful cinematography."[87] Some critics—notably Pauline Kael,[88] alongside Bosley Crowther and Andrew Sarris—have criticised the film as an incomplete and inaccurate portrayal of Lawrence.[89][90]

Awards and honours

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[91] | Best Picture | Sam Spiegel | Won |

| Best Director | David Lean | Won | |

| Best Actor | Peter O'Toole | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Omar Sharif | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay – Based on Material from Another Medium | Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction – Color | John Box, John Stoll and Dario Simoni | Won | |

| Best Cinematography – Color | Freddie Young | Won | |

| Best Film Editing | Anne V. Coates | Won | |

| Best Music Score – Substantially Original | Maurice Jarre | Won | |

| Best Sound | John Cox | Won | |

| American Cinema Editors Awards | Best Edited Feature Film | Anne V. Coates | Nominated |

| British Academy Film Awards[92] | Best Film from any Source | Won | |

| Best British Film | Won | ||

| Best British Actor | Peter O'Toole | Won | |

| Best Foreign Actor | Anthony Quinn | Nominated | |

| Best British Screenplay | Robert Bolt | Won | |

| British Society of Cinematographers[93] | Best Cinematography | Freddie Young | Won |

| David di Donatello Awards | Best Foreign Production | Sam Spiegel | Won |

| Best Foreign Actor | Peter O'Toole | Won[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Directors Guild of America Awards[94] | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | David Lean | Won |

| Golden Globe Awards[95] | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Won | |

| Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama | Peter O'Toole | Nominated | |

| Anthony Quinn | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Omar Sharif | Won | |

| Best Director – Motion Picture | David Lean | Won | |

| Most Promising Newcomer – Male | Peter O'Toole | Won | |

| Omar Sharif | Won | ||

| Best Cinematography – Color | Freddie Young | Won | |

| Grammy Awards[96] | Best Original Score from a Motion Picture or Television Show | Maurice Jarre | Nominated |

| International Film Music Critics Association Awards[97] | Best Archival Release of an Existing Score | Maurice Jarre, Nic Raine, Jim Fitzpatrick and Frank K. DeWald | Nominated |

| Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | David Lean | Won |

| Laurel Awards | Top Road Show | Won | |

| Top Male Dramatic Performance | Peter O'Toole | Nominated | |

| Top Male Supporting Performance | Omar Sharif | Nominated | |

| Top Song | Maurice Jarre (for the "Theme Song") | Nominated | |

| Nastro d'Argento | Best Foreign Director | David Lean | Won |

| National Board of Review Awards[98] | Top Ten Films | 4th Place | |

| Best Director | David Lean | Won | |

| National Film Preservation Board | National Film Registry | Inducted | |

| Online Film & Television Association Awards[99] | Hall of Fame – Motion Picture | Won | |

| Producers Guild of America Awards | PGA Hall of Fame – Motion Pictures | Sam Spiegel | Won |

| Saturn Awards | Best DVD or Blu-ray Special Edition Release | Lawrence of Arabia: 50th Anniversary Collector's Edition | Nominated |

| Writers' Guild of Great Britain Awards | Best British Dramatic Screenplay | Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson | Won |

Legacy

Film director Steven Spielberg considers this his favourite film of all time and the one that inspired him to become a filmmaker,[100] crediting the film, which he saw four times in four successive weeks upon its release, with understanding "It was the first time seeing a movie, I realized there are themes that aren't narrative story themes, there are themes that are character themes, that are personal themes. [...] and I realized there was no going back. It was what I was going to do." [101]

Film director Kathryn Bigelow also considers it one of her favourite films, saying it inspired her to film The Hurt Locker in Jordan.[102] Lawrence of Arabia also inspired numerous other adventure, science fiction and fantasy stories in modern popular culture, including Frank Herbert's Dune franchise, George Lucas's Star Wars franchise, Ridley Scott's Prometheus (2012), George Miller's Mad Max: Fury Road (2015),[103] and Disney's Frozen franchise.[104] In 1991, Lawrence of Arabia was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected for preservation in the United States Library of Congress National Film Registry.[105] In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed the film as the seventh best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its membership.[106]

Later film

In 1990, the made-for-television film A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia was aired. It depicts events in the lives of Lawrence and Faisal subsequent to Lawrence of Arabia and featured Ralph Fiennes as Lawrence and Alexander Siddig as Prince Faisal.

See also

- BFI Top 100 British films

- Clash of Loyalties

- Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence

- List of films considered the best

- White savior narrative in film

- Whitewashing in film

Notes

- Tied with Fredric March for Seven Days in May.

References

- "Lawrence of Arabia (1962)" Archived 27 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, AFI Catalog.

- "Lawrence of Arabia". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- "Lawrence of Arabia (1962)". BFI. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- "Lawrence of Arabia – Box Office Data, DVD and Blu-ray Sales, Movie News, Cast and Crew Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Andrews, Robert M. (26 September 1991). "Cinema: 'Lawrence of Arabia' is among those selected for preservation by Library of Congress". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Turner 1994, pp. 41–45

- Lean, David (2009). David Lean: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-60473-234-4.

- Woolf, Christopher (16 December 2013). "Is Peter O'Toole's Lawrence of Arabia fact or fiction?". PRI. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Lane, Anthony (31 March 2008). "Master and Commander". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- Turner 1994, pp. 45–49

- Turner 1994, p. 49

- "Lawrence of Arabia or Smith in the Desert?". Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- Turner 1994, p. 51

- Turner 1994, pp. 137–38

- Daniel Eagan (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. A&C Black. pp. 586–. ISBN 978-0-8264-2977-3. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Baxter, Brian (4 January 2012). "Harry Fowler obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- BFI Film Classics – Lawrence Of Arabia Kevin Jackson pp. 59. 2007

- Phillips, Gene D. (2006). Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-8131-2415-5.

- Murphy, David The Arab Revolt 1916–1918, London: Osprey, 2008. p. 17

- Murphy, David The Arab Revolt 1916–1918, London: Osprey, 2008. p. 18

- Murphy, David The Arab Revolt 1916–1918, London: Osprey, 2008. p. 39

- Murphy, David The Arab Revolt 1916–1918, London: Osprey, 2008. pp. 43–44

- Murphy, David The Arab Revolt 1916–1918, London: Osprey, 2008 p. 24

- Orlans, Harold (2002). T. E. Lawrence: Biography of a Broken Hero. McFarland. p. 111. ISBN 0-7864-1307-7.

- Weintraub, Stanley (1964). "Lawrence of Arabia". Film Quarterly. 17 (3): 51–54. doi:10.2307/1210914. JSTOR 1210914.

- cf. Jeremy Wilson, Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence (1990), pp. 409–10

- Wilson, Jeremy. "Lawrence of Arabia or Smith in the Desert?". T. E. Lawrence Studies. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- L. Robert Morris and Lawrence Raskin. Lawrence of Arabia: The 30th Anniversary Pictorial History. pp. 149–156

- "The Seven Pillars Portraits". castlehillpress.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2006. Retrieved 21 January 2006.

- "General Allenby (biography)". pbs.org. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- "General Allenby (radio interview)". pbs.org. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Steven C. Caton, Lawrence of Arabia: A Film's Anthropology, p. 59

- "Prince Feisal". pbs.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Adrian Turner, Robert Bolt: Scenes From Two Lives, 201–06

- Korda, pp. 693–94

- Lawrence of Arabia: An Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood, Press, 2004. p. 24

- Murphy, David The Arab Revolt, Osprey: London, 2008 pp. 88–89

- Phillips, Gene D. (2006). Beyond the Epic: The Life & Films of David Lean. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-8131-2415-5.

- Brownlow 1996, pp. 410–11

- Sellers, Robert (2015). Peter O'Toole: The Definitive Biography. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-283-07216-1.

my bitterest disappointment

- Brownlow 1996, pp. 393–401

- Phillips, Gene D. (2006). Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-8131-2415-5.

- Phillips, Gene D. (2006). Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 270–82. ISBN 978-0-8131-2415-5.

- Brownlow 1996, p. 443

- "David Lean, Sorcerer of the Screen". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Bourne, Stephen (2016). Brief Encounters: Lesbians and Gays in British Cinema 1930-1971. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4742-9134-7.

- Phillips, Gene D. (2006). Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 291, 303. ISBN 978-0-8131-2415-5.

- Brownlow 1996, pp. 466–67

- Peter O'Toole, interview on the Late Show with David Letterman, 11 May 1995.

- Caton, Steven Charles (1950). Lawrence of Arabia: A Film's Anthropology. Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 70, 71. ISBN 0-520-21082-4.

- Santas, Constantine (2012). The Epic Films of David Lean. Plymouth UK: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. xxvi.

- "Peter O'Toole talks about 'Lawrence of Arabia' in rare 1963 interview". YouTube. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- The Economist. Obituary: Maurice Jarre. 16 April 2009.

- Oscars.org Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Awardsdatabase.oscars.org (29 January 2010).

- Maurice Jarre on Archived 25 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Afi.com (23 September 2005).

- BFI Film Classics – Lawrence Of Arabia Kevin Jackson pp90 2007

- Brownlow 1996, pp. 484, 705, 709

- Caton, S.C. (1999). Lawrence of Arabia: A Film's Anthropology (pp. 129–31). Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21082-4.

- "Festival de Cannes: Lawrence of Arabia". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- "anniversaryKarlovy Vary International Film Festival – Lawrence of Arabia". fullmovieis.org. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- "Lawrence of Arabia (re-release)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "Alternate versions for Lawrence of Arabia (1962)". imdb.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Director's Notes on Re-editing Lawrence of Arabia". davidlean.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2010.

- "Nielsen Top Ten, January 29th – February 4th, 1973". Television Obscurities – Tvobscurities.com. 16 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "Daily News from New York, New York on August 21, 1977 · 242". Newspapers.com. 21 August 1977. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- Apar, Bruce (5 April 2001). "Lawrence' Star O'Toole Marvels at DVD". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2001. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Rivero, Enrique (20 June 2002). "Columbia Trims Its DVDs". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2002. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- "Lawrence of Arabia (Collector's Edition) DVD". Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Wasser, Frederick (2010). Steven Spielberg's America. Polity America Through the Lens. Polity. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-7456-4082-2.

- Rob Sabin (20 December 2011). "Home Theater: Hollywood, The 4K Way". HomeTheater.com Ultimate Tech. Source Interlink Media. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- Lawrence of Arabia on Blu-ray Later This Year Archived 18 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Blu-rayDefinition.com (12 June 2012).

- Lawrence of Arabia Blu-ray Disc Release Finalized Archived 11 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Hometheater.about.com (7 August 2012).

- "CreativeCOW". creativecow.net. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Cannes Classics 2012 – Festival de Cannes 2013 (International Film Festival) Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Festival-cannes.fr.

- 'Jaws,' 'Lawrence of Arabia,' 'Once Upon a Time in America' and 'Tess' to Get the Cannes Classics Treatment | Filmmakers, Film Industry, Film Festivals, Awards & Movie Reviews Archived 26 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Indiewire (26 October 2012).

- Janela Internacional de Cinema do Recife | Festival Internacional de Cinema do Recife Archived 11 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Janeladecinema.com.br.

- cinequest.org

- LAWRENCE OF ARABIA: 60TH ANNIVERSARY LIMITED EDITION (4K UHD STEELBOOK REVIEW), retrieved 27 September 2021

- Lawrence of Arabia: The film that inspired Spielberg » Top 10 Films – Film Lists, Reviews, News & Opinion Archived 17 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Top 10 Films.

- American Film Institute (17 June 2008). "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- Film, Total. (18 September 2010) Lawrence Of Arabia: Two-Disc Set Review. TotalFilm.com.Archived 19 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "The directors' top ten films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Hastings, Chris; Govan, Fiona (15 August 2004). "Stars vote Lawrence of Arabia the best British film of all time". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. AFI. Retrieved 20 December 2013

- "Lawrence of Arabia (re-release)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive.

- "Lawrence of Arabia (1962)". rottentomatoes.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- "THE SOUND OF MUSIC: Kael's Fate". The New York Times. 3 September 2000. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- Crowther, Bosley (17 December 1962). "Screen: A Desert Warfare Spectacle:'Lawrence of Arabia' Opens in New York". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Liukkonen, Petri. "T.E. Lawrence". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011.

- "The 35th Academy Awards (1963) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1963". BAFTA. 1963. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- "15th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "Lawrence of Arabia – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "1963 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- IFMCA (2011). "2010 IFMCA Awards". IFMCA. IFMCA. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "1962 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "Film Hall of Fame Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- DVD documentary, A Conversation with Steven Spielberg

- Lacy, Susan (5 October 2021). Spielberg (Documentary film).

- "Kathryn Bigelow's 5 favourite films". 3 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "'Lawrence Of Arabia' Is The Unlikely Prequel To 'Star Wars,' 'Dune,' And All Your Favorite Fantasy Epics". Decider.com. New York Post. 3 December 2015. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Frozen creators: It's Disney – but a little different". Metro. 8 December 2013. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "25 Classics Join U.S. Film Registry : * Cinema: 'Lawrence of Arabia' is among those selected for preservation by Library of Congress". Los Angeles Times. 26 September 1991. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "The 75 Best Edited Films". Editors Guild Magazine. 1 (3). May 2012. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015.

Sources

- Brownlow, Kevin (1996). David Lean: A Biography. Richard Cohen Books. ISBN 978-1-86066-042-9.

- Turner, Adrian (1994). The Making of David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia. Dragon's World Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85028-211-2.

Further reading

- Morris, L. Robert and Raskin, Lawrence (1992). Lawrence of Arabia: The 30th Anniversary Pictorial History. Doubleday & Anchor, New York. A book on the creation of the film, authorised by Sir David Lean.

External links

- Lawrence of Arabia by Michael Wilmington on the National Film Registry website

- Lawrence of Arabia at IMDb

- Lawrence of Arabia at the TCM Movie Database

- Lawrence of Arabia at Box Office Mojo

- Lawrence of Arabia at Rotten Tomatoes

- Lawrence of Arabia at Metacritic

- Lawrence of Arabia at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Lawrence of Arabia essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 586-588

- The Making of Lawrence of Arabia, Digitised BAFTA Journal (Winter 1962–1963)

На других языках

[de] Lawrence von Arabien (Film)

Lawrence von Arabien ist ein britischer Monumental- und Historienfilm des Regisseurs David Lean und des Produzenten Sam Spiegel aus dem Jahr 1962, der sich an den autobiografischen Kriegsbericht Die sieben Säulen der Weisheit von Thomas Edward Lawrence anlehnt. Das bildmächtige Wüstenepos machte die Hauptdarsteller Peter O’Toole und Omar Sharif international bekannt und erhielt 1963 sieben Oscars.- [en] Lawrence of Arabia (film)

[es] Lawrence de Arabia (película)

Lawrence de Arabia (en inglés: Lawrence of Arabia) es una película británica de 1962 del género épica-histórica, dirigida por David Lean y basada en la vida de T. E. Lawrence. La cinta está interpretada por Peter O'Toole, Omar Sharif, Anthony Quinn, Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins, Anthony Quayle, José Ferrer, Claude Rains, Arthur Kennedy y Fernando Sancho, entre otros.[it] Lawrence d'Arabia (film)

Lawrence d'Arabia (Lawrence of Arabia) è un film colossal del 1962 diretto da David Lean, vincitore di sette Premi Oscar, tra cui quelli per il miglior film e la miglior regia.[ru] Лоуренс Аравийский (фильм)

«Лоуренс Аравийский» (англ. Lawrence of Arabia) — эпический кинофильм 1962 года режиссёра Дэвида Лина о Т. Э. Лоуренсе и событиях Арабского восстания 1916—1918 годов, удостоенный семи премий «Оскар», в том числе за лучший фильм. Фильм сделал начинающих актёров Питера О’Тула и Омара Шарифа мировыми кинозвёздами первой величины.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии