fiction.wikisort.org - Writer

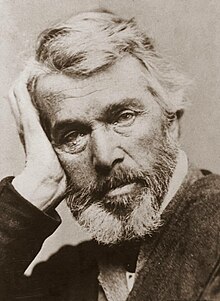

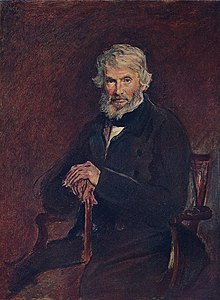

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 1795 – 5 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born of peasant parents in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Carlyle attended the University of Edinburgh where he excelled in mathematics, inventing the Carlyle circle. After finishing the arts course, he prepared to become a minister in the Burgher Church while working as a schoolmaster. He quit these and several other endeavours before settling on literature, writing for the Edinburgh Encyclopædia and working as a translator. He found initial success as a disseminator of German literature, then little-known to English readers, through his translations, his Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825), and his review essays for various journals. His first major work was a novel entitled Sartor Resartus (1833–34). After relocating to London, he became famous with his French Revolution (1837), which prompted the collection and reissue of his essays as Miscellanies. Each of his subsequent works, from On Heroes (1841) to History of Frederick the Great (1858–65) and beyond, were highly regarded throughout Europe and North America. He founded the London Library, contributed significantly to the creation of the National Portrait Galleries in London and Scotland,[1] was elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University in 1865, and received the Pour le Mérite in 1874, among other honours.

Carlyle's corpus spans the genres of history, the critical essay, social commentary, biography, fiction, and poetry. His innovative writing style, known as Carlylese, greatly influenced Victorian literature and anticipated techniques of postmodern literature.[2] While not adhering to any formal religion, he asserted the importance of belief and developed his own philosophy of religion. He preached "Natural Supernaturalism",[3] the idea that all things are "Clothes" which at once reveal and conceal the divine, that "a mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one",[4] and that duty, work and silence are essential. He postulated the Great Man theory, a philosophy of history which contends that history is shaped by exceptional individuals. He viewed history as a "Prophetic Manuscript" that progresses on a cyclical basis, analogous to the phoenix and the seasons. Raising the "Condition-of-England Question"[5] to address the impact of the Industrial Revolution, his political philosophy is characterised by medievalism, advocating a "Chivalry of Labour"[6] led by "Captains of Industry".[7] He attacked utilitarianism as mere atheism and egoism,[8] criticised laissez-faire political economy as the "Dismal Science",[9] and rebuked "big black Democracy"[10] while championing "Heroarchy (Government of Heroes)".

Carlyle occupied a central position in Victorian culture, being considered not only, in the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the "undoubted head of English letters",[11][12] but a secular prophet. Posthumously, his reputation suffered as publications by his friend and disciple James Anthony Froude provoked controversy about Carlyle's personal life, particularly his marriage to Jane Welsh Carlyle. His reputation further declined in the 20th century, as the onsets of World War I and World War II brought forth accusations that he was a progenitor of both Prussianism and fascism. Since the 1950s, extensive scholarship in the field of Carlyle Studies has improved his standing, and he is now recognised as "one of the enduring monuments of our literature who, quite simply, cannot be spared."[13]

Biography

Early life

Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James (1758–1832) and Margaret Aitken Carlyle (1771–1853) in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland. Nicholas Carlisle traced Carlyle's ancestry back to Margaret Bruce, sister of Robert the Bruce.[14] His parents were members of the Burgher secession Presbyterian church.[15] James Carlyle was a stonemason, later a farmer, who built the Arched House wherein his son was born. His maxim was that "man was created to work, not to speculate, or feel, or dream."[16] As a result of his disordered upbringing, James Carlyle became deeply religious in his youth, reading many books of sermons and doctrinal arguments throughout his life. He married his first wife in 1791, distant cousin Janet, who gave birth to John Carlyle and then died. He married Margaret Aitken in 1795, a poor farmer's daughter then working as a servant. They had nine children, of whom Thomas was the eldest. Margaret was pious and devout and hoped that Thomas would become a minister. She was close to her eldest son, being a "smoking companion, counselor and confidante" in Carlyle's early days. She suffered a manic episode when Carlyle was a teenager, in which she became "elated, disinhibited, over-talkative and violent."[17] She suffered another breakdown in 1817, which required her to be removed from her home and restrained.[18] Carlyle always spoke highly of his parents, and his character was deeply influenced by both of them.[19]

Carlyle's early education came from his mother, who taught him reading (despite being barely literate), and his father, who taught him arithmetic.[20] He first attended "Tom Donaldson's School" in Ecclefechan followed by Hoddam School (c. 1802–1806), which "then stood at the Kirk", located at the "Cross-roads" midway between Ecclefechan and Hoddam Castle.[21] By age 7, Carlyle showed enough proficiency in English that he was advised to "go into Latin", which he did with enthusiasm; however, the schoolmaster at Hoddam did not know Latin, so he was handed over to a minister that did, with whom he made a "rapid & sure way".[22] He then went to Annan Academy (c. 1806–1809), where he studied rudimentary Greek, read Latin and French fluently, and learned arithmetic "thoroughly well".[23] Carlyle was severely bullied by his fellow students at Annan, until he "revolted against them, and gave stroke for stroke"; he remembered the first two years there as among the most miserable of his life.[24]

Edinburgh, the ministry and teaching (1809–1818)

![Plaque at 22A Buccleuch Place, Edinburgh[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/02/Thomas_Carlyle_plaque%2C_Buccleuch_Place_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1419955.jpg/185px-Thomas_Carlyle_plaque%2C_Buccleuch_Place_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1419955.jpg)

In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend the University of Edinburgh (c. 1809–1814), where he studied mathematics with John Leslie, science with John Playfair and moral philosophy with Thomas Brown.[26] He gravitated to mathematics and geometry and displayed great talent in those subjects, being credited with the invention of the Carlyle circle. In the University library, he read many important works of eighteenth-century and contemporary history, philosophy, and belles-lettres.[27] He began expressing religious scepticism around this time, asking his mother to her horror, "Did God Almighty come down and make wheelbarrows in a shop?"[28] In 1813 he completed his arts curriculum and enrolled in a theology course at Divinity Hall the following academic year.[29] This was to be the preliminary of a ministerial career.

Carlyle began teaching at Annan Academy in June 1814.[30] He gave his first trial sermons in December 1814 and December 1815, both of which are lost.[31] By the summer of 1815 he had taken an interest in astronomy[32] and would study the astronomical theories of Pierre-Simon Laplace for several years.[33] In November 1816, he began teaching at Kirkcaldy, having left Annan. There, he made friends with Edward Irving, whose ex-pupil Margaret Gordon became Carlyle's "first love". In May 1817,[34] Carlyle abstained from enrolment in the theology course, news which his parents received with "magnanimity".[35] In the autumn of that year, he read De l'Allemagne (1813) by Germaine de Staël, which prompted him to seek a German teacher, with whom he learned the pronunciation.[36] In Irving's library, he read the works of David Hume and Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1789); he would later recall that

I read Gibbon, and then first clearly saw that Christianity was not true. Then came the most trying time of my life. I should either have gone mad or made an end of myself had I not fallen in with some very superior minds.[37]

Mineralogy, law and first publications (1818–1821)

In the summer of 1818, following a "Tour" with Irving through "Peebles-Moffat moor country", Carlyle made his first attempt at publishing, forwarding an article "of a descriptive Tourist kind" to "some Magazine Editor in Edinburgh", which was not published and is now lost.[38] In October, Carlyle resigned from his position at Kirkcaldy, and left for Edinburgh in November.[39] Shortly before his departure, he began to suffer from dyspepsia, which remained with him throughout his life.[40] He enrolled in a mineralogy class from November 1818 to April 1819, attending lectures by Robert Jameson,[41] and in January 1819 began to study German, desiring to read the mineralogical works of Abraham Gottlob Werner.[42] In February and March, he translated a piece by Jöns Jacob Berzelius,[43] and by September he was "reading Goethe".[44] In November he enrolled in "the class of Scots law", studying under David Hume (the advocate).[45] In December 1819 and January 1820, Carlyle made his second attempt at publishing, writing a review-article on Marc-Auguste Pictet's review of Jean-Alfred Gautier's Essai historique sur le problème des trois corps (1817) which went unpublished and is lost.[46] The law classes ended in March 1820 and he did not pursue the subject any further.[47]

In the same month, he wrote several articles for David Brewster's Edinburgh Encyclopædia (1808–1830), which appeared in October. These were his first published writings.[48] In May and June, Carlyle wrote a review-article on the work of Christopher Hansteen, translated a book by Friedrich Mohs, and read Goethe's Faust.[49] By the autumn, Carlyle had also learned Italian and was reading Vittorio Alfieri, Dante Alighieri and Sismondi,[50] though German literature was still his foremost interest, having "revealed" to him a "new Heaven and new Earth".[51] In March 1821, he finished two more articles for Brewster's encyclopedia, and in April he completed a review of Joanna Baillie's Metrical Legends (1821).[52]

In May, Carlyle was introduced to Jane Baillie Welsh by Irving in Haddington.[53] The two began a correspondence, and Carlyle sent books to her, encouraging her intellectual pursuits; she called him "my German Master".[54]

"Conversion": Leith Walk and Hoddam Hill (1821–1826)

During this time, Carlyle struggled with what he described as "the dismallest Lernean Hydra of problems, spiritual, temporal, eternal".[55] Spiritual doubt, lack of success in his endeavours, and dyspepsia were all damaging his physical and mental health, for which he found relief only in "sea-bathing". In early July 1821,[56] an "incident" occurred to Carlyle in Leith Walk, "during those 3 weeks of total sleeplessness, in which almost" his "one solace was that of a daily bathe on the sands between [Leith] and Portobello."[57] The incident was the beginning of Carlyle's "Conversion", the process by which he "'authentically took the Devil by the nose'"[58] and flung "him behind me".[59] It gave Carlyle courage in his battle against the "Hydra"; to his brother John, he wrote, "What is there to fear, indeed?"[60]

![Repentance Tower near the farm in Hoddam Hill, which Carlyle called a fit memorial for reflecting sinners.[61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Repentance_Tower.jpg/220px-Repentance_Tower.jpg)

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien Marie Legendre's Elements of Geometry. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the New Edinburgh Review, and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On Proportion", which Augustus De Morgan later called "as good a substitute for the fifth Book of Euclid as could have been given in that space".[62] Carlyle's translation of Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship (1824) and Travels (1825) and his biography of Schiller (1825) brought him a decent income, which had before then eluded him, and he garnered a modest reputation. He began corresponding with Goethe and made his first trip to London in 1824, meeting with prominent writers such as Thomas Campbell, Charles Lamb, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and gaining friendships with Anna Montagu, Bryan Waller Proctor, and Henry Crabb Robinson. He also travelled to Paris in October–November with Edward Strachey and Kitty Kirkpatrick, where he attended Georges Cuvier's introductory lecture on comparative anatomy, gathered information on the study of medicine, introduced himself to Legendre, was introduced by Legendre to Charles Dupin, observed Laplace and several other notables while declining offers of introduction by Dupin, and heard François Magendie read a paper on the "fifth pair of nerves".[63]

In May 1825, Carlyle moved into a cottage farmhouse in Hoddam Hill near Ecclefechan, which his father had leased for him. Carlyle lived with his brother Alexander, who, "with a cheap little man-servant", worked the farm, his mother, with one maid-servant, and his two youngest sisters, Jean and Jenny.[64] He had constant contact with the rest of his family, most of whom lived close by at Mainhill, a farm owned by his father.[65] Jane made a successful visit in September 1825. Whilst there, Carlyle wrote German Romance (1827), a collection of previously untranslated German novellas by Johann Karl August Musäus, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Ludwig Tieck, E. T. A. Hoffmann, and Jean Paul. In Hoddam Hill, Carlyle found respite from the "intolerable fret, noise and confusion" that he had experienced in Edinburgh, and observed what he described as "the finest and vastest prospect all round it I ever saw from any house", with "all Cumberland as in amphitheatre unmatchable".[64] Here, he completed his "Conversion" which began with the Leith Walk incident. He achieved "a grand and ever-joyful victory", in the "final chaining down, and trampling home, 'for good,' home into their caves forever, of all" his "Spiritual Dragons".[66] By May 1826, problems with the landlord and the agreement forced the family's relocation to Scotsbrig, a farm near Ecclefechan. Later in life, he remembered the year at Hoddam Hill as "perhaps the most triumphantly important of my life."[67]

Marriage, Comely Bank and Craigenputtock (1826–1834)

In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Carlyle were married at the Welsh family farm in Templand. Shortly after their marriage, the Carlyles moved into a modest home on Comely Bank in Edinburgh, that had been leased for them by Jane's mother. They lived there from October 1826 to May 1828. In that time, Carlyle published German Romance, began Wotton Reinfred, an autobiographical novel which he left unfinished, and published his first article for the Edinburgh Review, "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter" (1827). "Richter" was the first of many essays extolling the virtues of German authors, who were then little-known to English readers; "State of German Literature" was published in October.[68] In Edinburgh, Carlyle made contact with several distinguished literary figures, including Edinburgh Review editor Francis Jeffrey, John Wilson of Blackwood's Magazine, essayist Thomas De Quincey, and philosopher William Hamilton.[53] In 1827 Carlyle attempted to land the Chair of Moral Philosophy at St. Andrews without success, despite support from an array of prominent intellectuals, including Goethe.[69] He also made an unsuccessful attempt for a professorship at the University of London.

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834.[70] He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of Werner", "Goethe's Helena", "Goethe", "Burns", "The Life of Heyne" (each 1828), "German Playwrights", "Voltaire", "Novalis" (each 1829), "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter Again" (1830), "Cruthers and Jonson; or The Outskirts of Life: A True Story", "Luther's Psalm", and "Schiller" (each 1831). He began but did not complete a history of German literature, from which he drew material for essays "The Nibelungen Lied", "Early German Literature" and parts of "Historic Survey of German Poetry" (each 1831). He published early thoughts on the philosophy of history in "Thoughts on History" (1830) and wrote his first pieces of social criticism, "Signs of the Times" (1829) and "Characteristics" (1831).[71] "Signs" garnered the interest of Gustave d'Eichthal, a member of the Saint-Simonians, who sent Carlyle Saint-Simonian literature, including Henri de Saint-Simon's Nouveau Christianisme (1825), which Carlyle translated and wrote an introduction for.[72]

Most notably, he wrote Sartor Resartus. Finishing the manuscript in late July 1831, Carlyle began his search for a publisher, leaving for London in early August.[73] He and his wife lived there for the winter at 4 (now 33) Ampton Street, Kings Cross, in a house built by Thomas Cubitt.[74][75][76] The death of Carlyle's father in January 1832 and his inability to attend the funeral moved him to write the first of what would become the Reminiscences, published posthumously in 1881.[77] Carlyle had not found a publisher by the time he returned to Craigenputtock in March but he had initiated important friendships with Leigh Hunt and John Stuart Mill. That year, Carlyle wrote the essays "Goethe's Portrait", "Death of Goethe", "Goethe's Works", "Biography", "Boswell's Life of Johnson", and "Corn-Law Rhymes". Three months after their return from a January to May 1833 stay in Edinburgh, the Carlyles were visited at Craigenputtock by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson (and other like-minded Americans) had been deeply affected by Carlyle's essays and determined to meet him during the northern terminus of a literary pilgrimage; it was to be the start of a lifelong friendship and a famous correspondence. 1833 saw publication of the essays "Diderot" and "Count Cagliostro"; in the latter, Carlyle introduced the idea of "Captains of Industry".[78]

Chelsea (1834–1845)

In June 1834, the Carlyles moved into 5 Cheyne Row, Chelsea, which became their home for the remainder of their respective lives. Residence in London wrought a large expansion of Carlyle's social circle. He became acquainted with scores of leading writers, novelists, artists, radicals, men of science, Church of England clergymen, and political figures. Two of his most important friendships were with Lord and Lady Ashburton; though Carlyle's warm affection for the latter would eventually strain his marriage, the Ashburtons helped to broaden his social horizons, giving him access to circles of intelligence, political influence, and power.

Carlyle eventually decided to publish Sartor serially in Fraser's Magazine, with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory.[79] That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the French Revolution and set about researching and writing it shortly thereafter. Having completed the first volume after five months of writing, he lent the manuscript to Mill, who had been supplying him with materials for his research. One evening in March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's door appearing "unresponsive, pale, the very picture of despair". He had come to tell Carlyle that the manuscript was destroyed. It had been "left out", and Mill's housemaid took it for wastepaper, leaving only "some four tattered leaves". Carlyle was sympathetic: "I can be angry with no one; for they that were concerned in it have a far deeper sorrow than mine: it is purely the hand of Providence". The next day, Mill offered Carlyle £200, of which he would only accept £100. He began the volume anew shortly afterwards. Despite an initial struggle, he was not deterred, feeling like "a runner that tho' tripped down, will not lie there, but rise and run again."[80][81] By September, the volume was rewritten. That year, he wrote a eulogy for his friend, "Death of Edward Irving".[82]

In April 1836, with the intercession of Emerson, Sartor Resartus was first published in book form in Boston, soon selling out its initial run of five hundred copies.[83][84] Carlyle's three-volume history of the French Revolution was completed in January 1837 and sent to the press.[85] Contemporaneously, the essay "Memoirs of Mirabeau" was published,[86] as was "The Diamond Necklace" in January and February,[87] and "Parliamentary History of the French Revolution" in April.[88] In need of further financial security, Carlyle began a series of lectures on German literature in May, delivered extemporaneously in Willis' Rooms. The Spectator reported that the first lecture was given "to a very crowded and yet a select audience of both sexes." Carlyle recalled being "wasted and fretted to a thread, my tongue … dry as charcoal: the people were there, I was obliged to stumble in, and start. Ach Gott!"[89] Despite his inexperience as a lecturer and deficiency "in the mere mechanism of oratory," reviews were positive and the series proved profitable for him.[90]

During Carlyle's lecture series, The French Revolution: A History was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to Karl August Varnhagen von Ense that his earlier efforts to popularise German literature were beginning to produce results, and expressed his satisfaction: "Deutschland will reclaim her great Colony; we shall become more Deutsch, that is to say more English, at same time."[91] The French Revolution fostered the republication of Sartor Resartus in London in 1838 as well as a collection of his earlier writings in the form of the Critical and Miscellaneous Essays, facilitated in Boston with the aid of Emerson. Carlyle presented his second lecture series in April and June 1838 on the history of literature at the Marylebone Institution in Portman Square. The Examiner reported that at the end of the second lecture, "Mr. Carlyle was heartily greeted with applause."[92] Carlyle felt that they "went on better and better, and grew at last, or threatened to grow, quite a flaming affair."[93] He published two essays in 1838, "Sir Walter Scott", being a review of John Gibson Lockhart's biography, and "Varnhagen von Ense's Memoirs". In April 1839, Carlyle published "Petition on the Copyright Bill".[94] A third series of lectures was given in May on the revolutions of modern Europe, which the Examiner reviewed positively, noting after the third lecture that "Mr. Carlyle's audiences appear to increase in number every time."[95] Carlyle wrote to his mother that the lectures were met "with very kind acceptance from people more distinguished than ever; yet still with a feeling that I was far from the right lecturing point yet."[96] In July, he published "On the Sinking of the Vengeur"[97] and in December he published Chartism, a pamphlet in which he addressed the movement of the same name and raised the Condition-of-England question.

![Report in The Examiner of the speech that gave birth to The London Library,[98] given by Thomas Carlyle 24 June 1840](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cf/The_Proposed_London_Library.jpg/112px-The_Proposed_London_Library.jpg)

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History. Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of [sic] with sufficient éclat; the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad best I have yet given."[99] In the 1840 edition of the Essays, Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833.[100] Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh.[101] Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841.[102][103] He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books, Anthony Panizzi (despite the fact that Panizzi had allowed him many privileges not granted to other readers), and criticised him in a footnote to an article published in the Westminster Review as the "respectable Sub-Librarian".[104] Carlyle's eventual solution, with the support of a number of influential friends, was to call for the establishment of a private subscription library from which books could be borrowed.

Carlyle had chosen Oliver Cromwell as the subject for a book in 1840 and struggled to find what form it would take. In the interim, he wrote Past and Present (1843) and the articles "Baillie the Covenanter" (1841), "Dr. Francia" (1843), and "An Election to the Long Parliament" (1844). Carlyle declined an offer for professorship from St. Andrews in 1844. The first edition of Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: with Elucidations was published in 1845; it was a popular success, and did much to revise Cromwell's standing in Britain. [105] Financially secure, Carlyle wrote little in the years that immediately followed Cromwell.[106]

Journeys to Ireland and Germany (1846–1865)

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy for a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland.[107] Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in The Spectator in response to two speeches given by Peel wherein he made many of the same proposals which Carlyle had earlier suggested; he called the speeches "like a prophecy of better things, inexpressibly cheering."[108] In May, he published "Indian Meal", in which he advanced maize as a remedy to the Great Famine as well as the worries of "disconsolate Malthusians".[109] He visited Ireland again with Duffy later that year while recording his impressions in his letters and a series of memoranda, published as Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849 after his death; Duffy would publish his own memoir of their travels, Conversations with Carlyle.

Carlyle's travels in Ireland deeply affected his views on society, as did the Revolutions of 1848. While embracing the latter as necessary in order to cleanse society of various forms of anarchy and misgovernment, he denounced their democratic undercurrent and insisted on the need for authoritarian leaders. These events inspired his next two works, "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849), in which he coined the term "Dismal Science" to describe political economy, and Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850). The illiberal content of these works sullied Carlyle's reputation for some progressives, while endearing him to those that shared his views. In 1851, Carlyle wrote The Life of John Sterling as a corrective to Julius Hare's unsatisfactory 1848 biography. In late September and early October, he made his second trip to Paris, where he met Adolphe Thiers and Prosper Mérimée; his account, "Excursion (Futile Enough) to Paris; Autumn 1851", was published posthumously.

In 1852, Carlyle began research on Frederick the Great, whom he had expressed interest in writing a biography of as early as 1830.[110] He travelled to Germany that year, examining source documents and prior histories. Carlyle struggled through research and writing, telling von Ense it was "the poorest, most troublesome and arduous piece of work he has ever undertaken".[111] In 1856, the first two volumes of History of Friedrich II. of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great were sent to the press and published in 1858. During this time, he wrote "The Opera" (1852), "Project of a National Exhibition of Scottish Portraits" (1854) at the request of David Laing, and "The Prinzenraub" (1855). In October 1855, he finished The Guises, a history of the House of Guise and its relation to Scottish history, which was first published in 1981.[112] Carlyle made a second expedition to Germany in 1858 to survey the topography of battlefields, which he documented in Journey to Germany, Autumn 1858, published posthumously. In May 1863, Carlyle wrote the short dialogue "Ilias (Americana) in Nuce" (American Iliad in a Nutshell) on the topic of the American Civil War. Upon publication in August, the "Ilias" drew scornful letters from David Atwood Wasson and Horace Howard Furness.[113] In the summer of 1864, Carlyle lived at 117 Marina (built by James Burton)[114] in St Leonards-on-Sea, in order to be nearer to his ailing wife who was in possession of caretakers there.[115]

Carlyle planned to write four volumes but had written six by the time Frederick was finished in 1865. Before its end, Carlyle had developed a tremor in his writing hand.[116] Upon its completion, it was received as a masterpiece. He earned a sobriquet, the "Sage of Chelsea",[117] and in the eyes of those that had rebuked his politics, it restored Carlyle to his position as a great man of letters.[118] Carlyle was elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University in November 1865, succeeding William Ewart Gladstone and defeating Benjamin Disraeli by a vote of 657 to 310.[119]

Final years (1866–1881)

Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall, Thomas Henry Huxley and Thomas Erskine. One of those that welcomed Carlyle on his arrival was Sir David Brewster, president of the university and the commissioner of Carlyle's first professional writings for the Edinburgh Encyclopædia. Carlyle was joined onstage by his fellow travelers, Brewster, Moncure D. Conway, George Harvey, Lord Neaves and others. Carlyle spoke extemporaneously on several subjects, concluding his address with a quote from Goethe: "Work, and despair not: Wir heissen euch hoffen, 'We bid you be of hope!'" Tyndall reported to Jane in a three-word telegram that it was "A perfect triumph."[120] The warm reception he received in his homeland of Scotland marked the climax of Carlyle's life as a writer. While still in Scotland, Carlyle received abrupt news of Jane's sudden death in London. Upon her death, Carlyle began to edit his wife's letters and write reminiscences of her. He experienced feelings of guilt as he read her complaints about her illnesses, his friendship with Lady Harriet Ashburton, and his devotion to his labour, particularly on Frederick the Great. Although deep in grief, Carlyle remained active in public life.

Amidst controversy over governor John Eyre's violent repression of the Morant Bay rebellion, Carlyle assumed leadership of the Eyre Defence and Aid Fund in 1865 and 1866. The Defence had convened in response to the anti-Eyre Jamaica Committee, led by Mill and backed by Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer and others. Carlyle and the Defence were supported by John Ruskin, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Charles Dickens and Charles Kingsley.[121][122] From December 1866 to March 1867,[123] Carlyle resided at the home of Louisa Baring, Lady Ashburton in Menton, where he wrote reminiscences of Irving, Jeffrey, Robert Southey, and William Wordsworth. In August, he published "Shooting Niagara: And After?", an essay in response and opposition to the Second Reform Bill.[124] In 1868, he wrote reminiscences of John Wilson and William Hamilton, and his niece Mary Aitken Carlyle moved into 5 Cheyne Row, becoming his caretaker and assisting in the editing of Jane's letters. In March 1869, he met with Queen Victoria, who wrote in her journal of "Mr. Carlyle, the historian, a strange-looking eccentric old Scotchman, who holds forth, in a drawling melancholy voice, with a broad Scotch accent, upon Scotland and upon the utter degeneration of everything."[125] In 1870, he was elected president of the London Library, and in November he wrote a letter to The Times in support of Germany in the Franco-Prussian War. His conversation was recorded by a number of friends and visitors in later years, most notably William Allingham, who became known as Carlyle's Boswell.[126]

In the spring of 1874, Carlyle accepted the Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste from Otto von Bismarck and declined Disraeli's offers of a state pension and the Knight Grand Cross in the Order of the Bath in the autumn. On the occasion of his eightieth birthday in 1875, he was presented with a commemorative medal crafted by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm and an address of admiration signed by 119 of the leading writers, scientists, and public figures of the day.[lower-alpha 1] "Early Kings of Norway", a recounting of historical material from the Icelandic sagas transcribed by Mary acting as his amanuensis,[127] and an essay on "The Portraits of John Knox" (both 1875) were his last major writings to be published in his lifetime. In November 1876, he wrote a letter in the Times "On the Eastern Question", entreating England not to enter the Russo-Turkish War on the side of the Turks. Another letter to the Times in May 1877 "On the Crisis", urging against the rumoured wish of Disraeli's to send a fleet to the Baltic Sea and warning not to provoke Russia and Europe at large into a war against England, marked his last public utterance.[128] The American Academy of Arts and Sciences elected him a Foreign Honorary Member in 1878.[129]

On 2 February 1881, Carlyle fell into a coma. For a moment he awakened, and Mary heard him speak his final words: "So this is Death—well . . ."[130] He thereafter lost his speech and died on the morning of 5 February.[131] An offer of interment at Westminster Abbey, which he had anticipated, was declined by his executors in accordance with his will.[132] He was laid to rest with his mother and father in Hoddam Kirkyard in Ecclefechan, according to old Scottish custom.[133] His private funeral, held on 10 February, was attended by family and a few friends, including Froude, Conway, Tyndall, and William Lecky, as local residents looked on.[134]

Philosophy

Carlyle's religious, historical and political thought has long been the subject of debate. In the 19th century, he was "an enigma" according to Ian Campbell in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, being "variously regarded as sage and impious, a moral leader, a moral desperado,[lower-alpha 2] a radical, a conservative, a Christian."[136] Carlyle continues to perplex scholars in the 21st century, as Kenneth J. Fielding quipped in 2005: "A problem in writing about Carlyle and his beliefs is that people think that they know what they are."[137]

Carlyle identified two philosophical precepts.[138] The first is derived from Novalis: "The True philosophical Act is annihilation of self (Selbsttödtung); this is the real beginning of all Philosophy; all requisites for being a Disciple of Philosophy point hither."[139] The second is derived from Goethe: "It is only with Renunciation (Entsagen) that Life, properly speaking, can be said to begin."[140] Through Selbsttödtung (annihilation of self), liberation from material, self-imposed constraints, which arise from the misguided pursuit of unfulfilling happiness and result in atheism and egoism, is achieved. With this liberation and Entsagen (renunciation, or humility)[141] as the guiding principle of conduct, it is seen that "there is in man a HIGHER than Love of Happiness: he can do without Happiness, and instead thereof find Blessedness!"[140] "Blessedness" refers to the serving of duty and the sense that the universe and everything in it, including humanity, is meaningful and united as one whole. Awareness of the fraternal bond of mankind brings discovery of the "Divine Depth of Sorrow", the feeling of "an infinite Love, an infinite Pity" for one's "fellowman".[142][143]

Natural Supernaturalism

Carlyle rejected doctrines which profess to fully know the true nature of God, believing that to possess such knowledge is impossible. In an 1835 letter, he asked, "Wer darf ihn NENNEN [Who dares name him]? I dare not, and do not", while rejecting charges of pantheism and expressing the empirical basis of his belief:

Finally assure yourself I am neither Pagan nor Turk, nor circumcised Jew, but an unfortunate Christian individual resident at Chelsea in this year of Grace; neither Pantheist nor Pottheist, nor any Theist or ist whatsoever; having the most decided contem[pt] for all manner of System-builders and Sectfounders—as far as contempt may be com[patible] with so mild a nature; feeling well beforehand (taught by long experience) that all such are and even must be wrong. By God's blessing, one has got two eyes to look with; also a mind capable of knowing, of believing: that is all the creed I will at this time insist on.[144]

With this empirical basis, Carlyle conceived of a "new Mythus",[145] Natural Supernaturalism.

Following Kant's distinction between Reason (Vernunft) and Understanding (Verstand) in Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Carlyle held the former to be the superior faculty, allowing for insight into the transcendent.[146] Hence, Carlyle saw all things symbols, or clothes, representing the eternal and infinite.[147] In Sartor, he defines the "Symbol proper" as that in which there is "some embodiment and revelation of the Infinite; the Infinite is made to blend itself with the Finite, to stand visible, and as it were, attainable there."[148] Carlyle writes: "All visible things are emblems . . . all Emblematic things are properly Clothes". Therefore, "Language is the Flesh-Garment, the Body, of Thought",[149] and "the Universe is but one vast Symbol of God", as is "man himself".[148]

In On Heroes, Carlyle spoke of

the sacred mystery of the Universe; what Goethe calls 'the open secret.'[lower-alpha 3] . . . open to all, seen by almost none! That divine mystery, which lies everywhere in all Beings, 'the Divine Idea of the World,' that which lies at 'the bottom of Appearance,' as Fichte styles it;[lower-alpha 4] of which all Appearance . . . is but the vesture, the embodiment that renders it visible.[152]

The "Divine Idea of the World", the belief in an eternal, omnipresent and metaphysical order which lies in the "unknown Deep"[153] of nature, is at the core of Natural Supernaturalism.[154]

Bible of Universal History

Carlyle revered what he called the "Bible of Universal History",[155] a "real Prophetic Manuscript"[156] which incorporates the poetic and the factual to show the divine reality of existence.[157] For Carlyle, "the right interpretation of Reality and History"[158] is the highest form of poetry, and "true History" is "the only possible Epic".[159] He imaged the "burning of a World-Phoenix" to represent the cyclical nature of civilisations as they undergo death and "Palingenesia, or Newbirth".[160] Periods of creation and destruction do overlap, however, and before a World-Phoenix is completely reduced to ashes, there are "organic filaments, mysteriously spinning themselves",[161] elements of regeneration amidst degeneration,[162] such as hero-worship, literature, and the unbreakable connection between all human beings.[88] Akin to the seasons, societies have autumns of dying faiths, winters of decadent atheism, springs of burgeoning belief and brief summers of true religion and government.[163] Carlyle saw history since the Reformation as a process of decay culminating in the French Revolution, out of which renewal must come, "for lower than that savage Sansculottism men cannot go."[164] Heroism is central to Carlyle's view of history. He saw individual actors as the prime movers of historical events: "The History of the world is but the Biography of great men."[165]

In the area of historiography, Carlyle focused on the complexity involved in faithfully representing both the facts of history and their meaning. He perceived "a fatal discrepancy between our manner of observing [passing things], and their manner of occurring",[166] since "History is the essence of innumerable Biographies" and every individual's experience varies, as does the "general inward condition of Life" throughout the ages.[167] Furthermore, even the best of historians, by necessity, presents history as a "series" of "successive" instances (a narrative) rather than as a "group" of "simultaneous" things done (an action), which is how they occurred in reality. Every single event is related to all others before and after it in "an ever-living, ever-working Chaos of Being". Events are multi-dimensional, possessing the physical properties of "breadth", "depth" and "length", and are ultimately based on "Passion and Mystery", characteristics that narrative, which is by its nature one-dimensional, fails to render. Emphasising the disconnect between the typical discipline of history and history as lived experience, Carlyle writes: "Narrative is linear, Action is solid."[168] He distinguishes between the "Artist in History" and the "Artisan in History". The "Artisan" works with historical facts in an atomised, mechanical way, while the "Artist" brings to his craft "an Idea of the Whole", through which the essential truth of history is successfully communicated to the reader.[156][169]

Heroarchy (Government of Heroes)

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

|

As with history, Carlyle believed that "Society is founded on Hero-worship. All dignities of rank, on which human association rests, are what we may call a Heroarchy (Government of Heroes)".[170] This fundamental assertion about the nature of society itself informed his political doctrine. Noting that the etymological root meaning of the word "King" is "Can" or "Able", Carlyle put forth his ideal government in "The Hero as King":

Find in any country the Ablest Man that exists there; raise him to the supreme place, and loyally reverence him: you have a perfect government for that country; no ballot-box, parliamentary eloquence, voting, constitution-building, or other machinery whatsoever can improve it a whit. It is in the perfect state; an ideal country.

Carlyle did not believe in hereditary monarchy but in a kingship based on merit. He continues:

The Ablest Man; he means also the truest-hearted, justest, the Noblest Man: what he tells us to do must be precisely the wisest, fittest, that we could anywhere or anyhow learn;—the thing which it will in all ways behoove us, with right loyal thankfulness, and nothing doubting, to do! Our doing and life were then, so far as government could regulate it, well regulated; that were the ideal of constitutions.[171]

It was for this reason that he regarded the Reformation, the English Civil War and the French Revolution as triumphs of truth over falsehood, despite their undermining of necessary societal institutions.[172]

Chivalry of Labour

Carlyle advocated a new kind of hero for the age of industrialisation: the Captain of Industry, who would re-imbue workhouses with dignity and honour. Instead of competition and "Cash Payment", which had become "the universal sole nexus of man to man",[173] the Captain of Industry would oversee the Chivalry of Labour, in which loyal labourers and enlightened employers are joined together "in veritable brotherhood, sonhood, by quite other and deeper ties than those of temporary day's wages!"[174]

Glossary

The 1907 edition of The Nuttall Encyclopædia contains entries on the following Carlylean terms:[175]

- Cash Nexus

- The reduction (under capitalism) of all human relationships, but especially relations of production, to monetary exchange.[lower-alpha 5]

- Clothes

- Carlyle's name in "Sartor Resartus" for the guises which the spirit, especially of man, weaves for itself and wears, and by which it both conceals itself in shame and reveals itself in grace.

| Part of a series on |

| Critique of political economy |

|---|

- Dismal Science

- Carlyle's name for the political economy that with self-complacency leaves everything to settle itself by the law of supply and demand, as if that were all the law and the prophets. The name is applied to every science that affects to dispense with the spiritual as a ruling factor in human affairs.

- Eternities, The Conflux of

- Carlyle's expressive phrase for Time, as in every moment of it a centre in which all the forces to and from Eternity meet and unite, so that by no past and no future can we be brought nearer to Eternity than where we at any moment of Time are; the Present Time, the youngest born of Eternity, being the child and heir of all the Past times with their good and evil, and the parent of all the Future, the import of which (see Matt. xvi. 27) it is accordingly the first and most sacred duty of every successive age, and especially the leaders of it, to know and lay to heart as the only link by which Eternity lays hold of it and it of Eternity.

- Everlasting No, The

- Carlyle's name for the spirit of unbelief in God, especially as it manifested itself in his own, or rather Teufelsdröckh's, warfare against it; the spirit, which, as embodied in the Mephistopheles (q. v.) of Goethe, is for ever denying,—der stets verneint—the reality of the divine in the thoughts, the character, and the life of humanity, and has a malicious pleasure in scoffing at everything high and noble as hollow and void.

- Everlasting Yea, The

- Carlyle's name for the spirit of faith in God in an express attitude of clear, resolute, steady, and uncompromising antagonism to the Everlasting No, on the principle that there is no such thing as faith in God except in such antagonism, no faith except in such antagonism against the spirit opposed to God.

- Gigman

- Carlyle's name for a man who prides himself on, and pays all respect to, respectability; derived from a definition once given in a court of justice by a witness who, having described a person as respectable, was asked by the judge in the case what he meant by the word; "one that keeps a gig", was the answer.[lower-alpha 6]

- Hallowed Fire

- an expression of Carlyle's in definition of Christianity "at its rise and spread"[lower-alpha 7] as sacred, and kindling what was sacred and divine in man's soul, and burning up all that was not.

- Immensities, Centre of

- an expression of Carlyle's to signify that wherever any one is, he is in touch with the whole universe of being, and is, if he knew it, as near the heart of it there as anywhere else he can be.

- Logic Spectacles

- Carlyle's name for eyes that can only discern the external relations of things, but not the inner nature of them.

- Mights and Rights

- the Carlyle doctrine that Rights are nothing till they have realised and established themselves as Mights; they are rights first only then.

- Natural Supernaturalism

- Carlyle's name in "Sartor" for the supernatural found latent in the natural, and manifesting itself in it, or of the miraculous in the common and everyday course of things; name of a chapter which, says Dr. Stirling, "contains the very first word of a higher philosophy as yet spoken in Great Britain, the very first English word towards the restoration and rehabilitation of the dethroned Upper Powers";[lower-alpha 8] recognition at bottom, as the Hegelian philosophy teaches, and the life of Christ certifies, of the finiting of the infinite in the transitory forms of space and time.

- Pig-Philosophy

- the name given by Carlyle in his "Latter-Day Pamphlets", in the one on Jesuitism, to the wide-spread philosophy of the time, which regarded the human being as a mere creature of appetite instead of a creature of God endowed with a soul, as having no nobler idea of well-being than the gratification of desire—that his only Heaven, and the reverse of it his Hell.

- Plugson of Undershot[lower-alpha 9]

- Carlyle's name in "Past and Present" for a member or "Master-Worker" of the English mammon-worshipping manufacturing class in rivalry with the aristocracy for the ascendency in the land, who pays his workers his wages and thinks he has done his duty with them in so doing, and is secure in the fortune he has made by that cash-payment gospel of his as all the law and the prophets, called of "Undershot", his mill being driven by a wheel, the working power of which is hidden unheeded by him, to break out some day to the damage of both his mill and him.

- Present Time

- defined by Carlyle as "the youngest born of Eternity, child and heir of all the past times, with their good and evil, and parent of all the future with new questions and significance",[lower-alpha 10] on the right or wrong understanding of which depend the issues of life or death to us all, the sphinx riddle given to all of us to rede as we would live and not die.

- Printed Paper

- Carlyle's satirical name for the literature of France prior to the Revolution.

- Progress of the Species Magazines

- Carlyle's name for the literature of the day which does nothing to help the progress in question, but keeps idly boasting of the fact, taking all the credit to itself, like Æseop's fly on the axle of the careening chariot soliloquising, "What a dust I raise!"

- Sauerteig

- (i.e. leaven), an imaginary authority alive to the "celestial infernal"[lower-alpha 11] fermentation that goes on in the world, who has an eye specially to the evil elements at work, and to whose opinion Carlyle frequently appeals in his condemnatory verdict on sublunary things.

- Silence, Worship of

- Carlyle's name for the sacred respect for restraint in speech till "thought has silently matured itself, . . . to hold one's tongue till some meaning lie behind to set it wagging",[lower-alpha 12] a doctrine which many misunderstand, almost wilfully, it would seem; silence being to him the very womb out of which all great things are born.

- Sincerity

- in Carlyle's ethics the one test of all worth in a human being, that he really with his whole soul means what he is saying and doing, and is courageously ready to front time and eternity on the stake.

- Tailors

- Carlyle's humorous name in "Sartor" for the architects of the customs and costumes woven for human wear by society, the inventors of our spiritual toggery, the truly poetic class.

- Weissnichtwo (Know-not-where)

- in Carlyle's "Sartor", an imaginary European city, viewed as the focus, and as exhibiting the operation, of all the influences for good and evil of the time we live in, described in terms which characterised city life in the first quarter of the 19th century; so universal appeared the spiritual forces at work in society at that time that it was impossible to say where they were and where they were not, and hence the name of the city, Know-not-where.

Style

Carlyle believed that his time required a new approach to writing:

But finally do you reckon this really a time for Purism of Style; or that Style (mere dictionary style) has much to do with the worth or unworth of a Book? I do not: with whole ragged battallions of Scott's-Novel Scotch, with Irish, German, French and even Newspaper Cockney (when "Literature" is little other than a Newspaper) storming in on us, and the whole structure of our Johnsonian English breaking up from its foundations,—revolution there as visible as anywhere else![178]

Carlyle's style lends itself to several nouns, the earliest being Carlylism from 1841. The Oxford English Dictionary records Carlylese, the most commonly used of these terms, as having first appeared in 1858.[179] Carlylese makes characteristic use of certain literary, rhetorical and grammatical devices, including apostrophe, apposition, archaism, exclamation, imperative mood, inversion, parallelism, portmanteau, present tense, neologisms, metaphor, personification, and repetition.[180][181]

Carlylese

At the beginning of his literary career, Carlyle worked to develop his own style, cultivating one of intense energy and visualisation, characterised not by "balance, gravity, and composure" but "imbalance, excess, and excitement."[182] Even in his early anonymous periodical essays his writing distinguished him from his contemporaries. Carlyle's writing in Sartor Resartus is described as "a distinctive mixture of exuberant poetic rhapsody, Germanic speculation, and biblical exhortation, which Carlyle used to celebrate the mystery of everyday existence and to depict a universe suffused with creative energy."[183]

Carlyle's approach to historical writing was inspired by a quality that he found in the works of Goethe, Bunyan and Shakespeare: "Everything has form, everything has visual existence; the poet's imagination bodies forth the forms of things unseen, his pen turns them to shape."[184] He rebuked typical, Dryasdust historiography: "Dull Pedantry, conceited idle Dilettantism,—prurient Stupidity in what shape soever,—is darkness and not light!"[185] Rather than reporting events in a detached, distanced manner, he presents immediate, tangible occurrences, often in the present tense.[186] In his French Revolution, "the great prose epic of the nineteenth century", Carlyle managed to craft an overwhelmingly original voice, producing deliberate tension by combining the common language of the time with self-conscious allusions to traditional epics, Homer, Shakespeare, Milton, or some contemporary French history source in nearly every sentence of its three volumes.

Carlyle's social criticism directs his penchant for metaphor toward the Condition-of-England question, depicting a thoroughly diseased society. Declaiming the aimlessness and infirmity of English leadership, Carlyle made use of satirical characters like Sir Jabesh Windbag and Bobus of Houndsditch in Past and Present. Memorable catchphrases such as Morrison's Pill, the Gospel of Mammonism, and "Doing as One Likes" were employed to counteract empty platitudes of the day. Carlyle transformed his depicted reality in various ways, whether by conversion of actual human beings into grotesque caricatures, envisioning isolated facts as emblems of morality, or by manifestation of the supernatural; in the Pamphlets, pampered felons appear in nightmarish visions and wrongheaded philanthropists wallow in their own filth.

Carlyle could at once use imaginative powers of rhetoric and vision to "render the familiar unfamiliar". He could also be a sharp-eyed, keen observer of the actual, reproducing scenes with imagistic clarity, as he does in the Reminiscences, the Life of John Sterling and the letters; he has often been called the Victorian Rembrandt.[187][188][189] As Mark Cumming explains, "Carlyle's intense appreciation of visual existence and of the innate energy of object, coupled with his insistent awareness of language and his daunting verbal resources, formed the immediate and lasting appeal of his style."[190]

Coinages

| Type | Number | Author rank |

|---|---|---|

| Total quotations[lower-alpha 13] | 6778 | 26th |

| First quotations[lower-alpha 14] | 547 | 45th |

| First quotations in a special sense[lower-alpha 15] | 1789 | 33rd |

The present table represents data gathered from Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2012. An explanatory footnote is provided for each "Type".

Over fifty percent of these entries come from Sartor Resartus, French Revolution, and History of Frederick the Great. Of the 547 First Quotations cited by the O.E.D., 87 or 16% are listed as being "in common use today."[191]

Humour

Carlyle's sense of humour and use of humorous characters was shaped by early readings of Cervantes, Samuel Butler, Jonathan Swift, and Laurence Sterne. He initially attempted a fashionable irony in his writing, which he soon abandoned in favour of a "deeper spirit" of humour. In his essays on Jean Paul, Carlyle rejects the dismissive, ironic humour of Voltaire and Molière, embracing the warm and sympathetic approach of Jean Paul and Cervantes. Carlyle establishes humour in many of his works through his use of characters, such as the Editor (in Sartor Resartus), Diogenes Teufelsdröckh (lit. 'God-born Devil's-dung'), Gottfried Sauerteig, Dryasdust, and Smelfungus. Linguistically, Carlyle explores the humorous possibilities of his subject through exaggerated and dazzling wordplay, "in sentences abounding with rhetorical devices: emphasis by capitalization, punctuation marks, and italics; allegory, symbol, and other poetic devices; hyphenated words, Germanic translations and etymologies; quotations, self-quotations, and bizarre allusions; and repetitious and antiquated speech."[192]

Allusion

Carlyle's writing is highly allusive. Ruth apRoberts writes that "Thomas Carlyle may well be, of all writers in English, the most thoroughly imbued with the Bible. His language, his imagery, his syntax, his stance, his worldview—are all affected by it."[193] Job, Ecclesiastes, Psalms and Proverbs are Carlyle's most frequently referenced books of the Old Testament, and Matthew that of the New Testament.[194] The structure of Sartor uses a basic typological Biblical pattern.[195] The French Revolution is filled with dozens of Homeric allusions, quotations, and a liberal use of epithets drawn from Homer as well as Homeric epithets of Carlyle's own devising.[196] The influence of Homer, particularly his attention to detail, his strongly visual imagination, and his appreciation of language, is also seen in Past and Present and Frederick the Great.[197] The language and imagery of John Milton is present throughout Carlyle's writings. His letters are full of allusions to a wide range of Milton's texts, including Lycidas, L'Allegro, Il Penseroso, Comus, Samson Agonistes and, most frequently, Paradise Lost.[198] Carlyle's works abound with direct and indirect references to William Shakespeare. The French Revolution contains two dozen allusions to Hamlet alone, and dozens more to Macbeth, Othello, Julius Caesar, King Lear, Romeo and Juliet, the histories, and the comedies.[199]

Reception

The earliest literary criticism on Carlyle is an 1835 letter from Sterling, who complained of the "positively barbarous" use of words in Sartor, such as "environment," "stertorous," and "visualised," words "without any authority" that are now widely used.[200] William Makepeace Thackeray recorded his mixed response in his 1837 review of French Revolution, decrying its "Germanisms and Latinisms" while acknowledging that "with perseverance, understanding follows, and things perceived first as faults are seen to be part of his originality, and powerful innovations in English prose."[201]

Henry David Thoreau expressed appreciation in "Thomas Carlyle and His Works":

Indeed, for fluency and skill in the use of the English tongue, he is a master unrivalled. His felicity and power of expression surpass even his special merits as historian and critic. . . . we had not understood the wealth of the language before. . . . He does not go to the dictionary, the wordbook, but to the word-manufactory itself, and has made endless work for the lexicographers . . . it would be well for any who have a lost horse to advertise, or a town-meeting warrant, or a sermon, or a letter to write, to study this universal letter-writer, for he knows more than the grammar or the dictionary.[202]

Oscar Wilde wrote that among the very few masters of English prose, "We have Carlyle, who should not be imitated."[203] Matthew Arnold advised: "Flee Carlylese as you would the devil."[204]

Frederic Harrison deemed Carlyle the "literary dictator of Victorian prose."[205] T. S. Eliot complained that "Carlyle partly originates and partly marks the disturbances in the equilibrium of English prose style", a problem that only disappeared with Ulysses.[206] Indeed, Georg B. Tennyson remarked that "not until Joyce is there a comparable inventiveness in English prose."[207]

Character

![Medallion of Carlyle by Thomas Woolner, 1851. James Caw said that it recalled Lady Eastlake's description of him: The head of a thinker, the eye of a lover, and the mouth of a peasant.[208]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Thomas_Carlyle_in_1851._Medallion_modeled_by_Thomas_Woolner.jpg/220px-Thomas_Carlyle_in_1851._Medallion_modeled_by_Thomas_Woolner.jpg)

Froude recalled his first impression of Carlyle:

He was then fifty-four years old; tall (about five feet eleven), thin, but at that time upright, with no signs of the later stoop. His body was angular, his face beardless, such as it is represented in Woolner's medallion,[lower-alpha 16] which is by far the best likeness of him in the days of his strength. His head was extremely long, with the chin thrust forward; his neck was thin; the mouth firmly closed, the under lip slightly projecting; the hair grizzled and thick and bushy. His eyes, which grew lighter with age, were then of a deep violet, with fire burning at the bottom of them, which flashed out at the least excitement. The face was altogether most striking, most impressive in every way.[209]

He was often recognised by his wideawake hat.[210]

Carlyle was a renowned conversationalist. Emerson described him as "an immense talker, as extraordinary in his conversation as in his writing,—I think even more so." Darwin considered him "the most worth listening to, of any man I know."[211] Lecky noted his "singularly musical voice" which "quite took away anything grotesque in the very strong Scotch accent" and "gave it a softening or charm".[212] Henry Fielding Dickens recollected that he was "gifted with a high sense of humour, and when he laughed he did so heartily, throwing his head back and letting himself go."[213] Thomas Wentworth Higginson remembered his "broad, honest, human laugh," one that "cleared the air like thunder, and left the atmosphere sweet."[214] Lady Eastlake called it "the best laugh I ever heard".

Charles Eliot Norton wrote that Carlyle's "essential nature was solitary in its strength, its sincerity, its tenderness, its nobility. He was nearer Dante than any other man."[215] Harrison similarly observed that "Carlyle walked about London like Dante in the streets of Verona, gnawing his own heart and dreaming dreams of Inferno. To both the passers-by might have said, See! there goes the man who has seen hell".[216] Higginson rather felt that Jean Paul's humorous character Siebenkäs "came nearer to the actual Carlyle than most of the grave portraitures yet executed", for, like Siebenkäs, Carlyle was "a satirical improvisatore".[217] Emerson saw Carlyle as "not mainly a scholar," but "a practical Scotchman, such as you would find in any saddler's or iron-dealer's shop, and then only accidentally and by a surprising addition, the admirable scholar and writer he is."[218]

Paul Elmer More found Carlyle "a figure unique, isolated, domineering—after Dr. Johnson the greatest personality in English letters, possibly even more imposing than that acknowledged dictator."[219]

Legacy

Influence

George Eliot summarised Carlyle's impact in 1855:

It is an idle question to ask whether his books will be read a century hence: if they were all burnt as the grandest of Suttees on his funeral pile, it would be only like cutting down an oak after its acorns have sown a forest. For there is hardly a superior or active mind of this generation that has not been modified by Carlyle's writings; there has hardly been an English book written for the last ten or twelve years that would not have been different if Carlyle had not lived.[220]

Carlyle's two most important followers were Emerson and Ruskin. In the 19th century, Emerson was often thought of as "the American Carlyle".[221] He sent Carlyle one of his books in 1870 with the inscription, "To the General in Chief from his Lieutenant".[222] In 1854, Ruskin made his first public acknowledgement that Carlyle was the author to whom he "owed more than to any other living writer".[223] After reading Ruskin's Unto This Last (1860), Carlyle felt that they were "in a minority of two", a feeling which Ruskin shared.[224][225] From the 1860s onward, Ruskin frequently referred to him as his "master" and "papa," writing after Carlyle's death that he was "throwing myself now into the mere fulfilment of Carlyle's work."[226]

By 1960, Carlyle had become "the single most frequent topic of doctoral dissertations in the field of Victorian literature".[227] While preparing for a study of his own, German scholar Gerhart von Schulze-Gävernitz found himself overwhelmed by the amount of material already written about Carlyle—in 1894.[13]

Literature

"The most explosive impact in English literature during the nineteenth century is unquestionably Thomas Carlyle's", writes Lionel Stevenson. "From about 1840 onward, no author of prose or poetry was immune from his influence."[228]

!['Carlyle and Tennyson talked and smoked together.' by J. R. Skelton, 1920. Carlyle on Tennyson: I do not meet, in these late decades, such company over a pipe![229]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7a/Carlyle_%28right%29_and_Tennyson_talking_and_smoking.jpg/189px-Carlyle_%28right%29_and_Tennyson_talking_and_smoking.jpg)

Authors on whom Carlyle's influence was particularly strong include Matthew Arnold,[230] Elizabeth Barrett Browning,[231] Robert Browning,[232] Arthur Hugh Clough,[233] Dickens, Disraeli, George Eliot,[234] Elizabeth Gaskell,[235] Frank Harris,[236] Kingsley, George Henry Lewes,[237] David Masson, George Meredith,[238] Mill, Margaret Oliphant, Marcel Proust,[239][240] Ruskin, George Bernard Shaw[241] and Walt Whitman.[242] Germaine Brée has shown the considerable impact that Carlyle had on the thought of André Gide.[243] Carlylean influence is also seen in the writings of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Marcu Beza, Jorge Luis Borges, the Brontës,[244] Arthur Conan Doyle, E. M. Forster, Ángel Ganivet, Lafcadio Hearn, William Ernest Henley, Marietta Holley, Rudyard Kipling,[245] Selma Lagerlöf, Herman Melville,[246] Edgar Quinet, Samuel Smiles, Lord Tennyson, William Makepeace Thackeray, Anthony Trollope, Miguel de Unamuno, Alexandru Vlahuță and Vasile Voiculescu.[247][248]

Carlyle's German essays and translations as well as his own writings were pivotal to the development of the English Bildungsroman.[249] His concept of symbols influenced French literary Symbolism.[250] Victorian specialist Alice Chandler writes that the influence of his medievalism is "found throughout the literature of the Victorian age".[251]

Carlyle's influence was also felt in the negative sense. Algernon Charles Swinburne, whose comments on Carlyle throughout his writings range from high praise to scathing critique, once wrote to John Morley that Carlyle was "the illustrious enemy whom we all lament", reflecting a view of Carlyle as a totalizing figure to be rebelled against.[252]

Despite the broad Modernist reaction against the Victorians, the influence of Carlyle has been traced in the writings of T. S. Eliot,[253] James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis[254] and D. H. Lawrence.[255]

Philosophy

J. H. Muirhead wrote that Carlyle "exercised an influence in England and America that no other did upon the course of philosophical thought of his time". Ralph Jessop has shown that Carlyle powerfully forwarded the Scottish School of Common Sense and reinforced it by way of further engagement with German idealism.[256] Examining his influence on late 19th- and early 20th-century philosophers, Alexander Jordan concluded that "Carlyle emerges as far-and-away the most prominent figure in a tradition of Scottish philosophy that stretched across three centuries and which culminated in British Idealism". His formative influence on British idealism touched its nearly every aspect, including its theology, its moral and ethical philosophy and its social and political thought. Leading British idealist F. H. Bradley cited from the "Everlasting Yea" chapter of Sartor Resartus in his argument against utilitarianism: "Love not Pleasure; love God."[257]

Carlyle had a foundational influence on American Transcendentalism. Virtually every member followed him with enthusiasm, including Amos Bronson Alcott, Louisa May Alcott, Orestes Brownson, William Henry Channing, Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Frederic Henry Hedge, Henry James Sr., Thoreau, and George Ripley.[258] James Freeman Clarke wrote that "He did not seem to be giving us a new creed, so much as inspiring us with a new life."[259]

Chandler writes that "Carlyle's contribution to English medievalism was first to make the contrast between modern and medieval England sharper and more horrifying than it had ever been." Secondly, he "gave new direction to the practical application of medievalism, transferring its field of action from agriculture, which was no longer the center of English life, to manufacturing, in which its lessons could be extremely valuable."[251]

G. K. Chesterton posited that "Out of [Carlyle] flows most of the philosophy of Nietzsche,"[260] a view held by many;[261][262][263][264] the connection has been studied since the late-nineteenth century.[265] But Nietzsche rejected this.[266]

Carlyle influenced the Young Poland movement, particularly its main thought leaders Stanisław Brzozowski and Antoni Lange.[267] In Romania, Titu Maiorescu of Junimea spread Carlyle's works, influencing Constantin Antoniade and others, including Panait Mușoiu, Constantin Rădulescu-Motru and Ion Th. Simionescu.[247]

Percival Chubb delivered an address on Carlyle to The Ethical Society of St. Louis in 1910. It was the first in a series entitled "Forerunners of Our Faith".[268]

Historiography

David R. Sorensen affirms that Carlyle "redeemed the study of history at a moment when it was being threatened by a host of convergent forces, including religious dogmatism, relativism, utilitarianism, Saint-Simonianism and Comtism" by defending the "miraculous dimension of the past" from attempts to make "history a science of progress, philosophy a justification of self-interest, and faith a matter of social convenience."[269] James Anthony Froude attributed his decision to become an historian to Carlyle's influence.[270] John Mitchel's Life of Aodh O'Neill, Prince of Ulster (1845) has been called "an early incursion of Carlylean thought into the romantic construction of the Irish nation".[271] Standish James O'Grady's presentation of a heroic past in his History of Ireland (1878–80) was strongly influenced by Carlyle.[272] Wilhelm Dilthey deemed Carlyle "the greatest English writer of the century".[273] Carlyle's histories were also praised by Heinrich von Treitschke,[274] Wilhelm Windelband,[275] George Peabody Gooch, Pieter Geyl, Charles Firth,[276] Nicolae Iorga, Vasile Pârvan and Andrei Oțetea.[247] Others were hostile to Carlyle's method, such as Thomas Babington Macaulay, Leopold von Ranke, Lord Acton, Hippolyte Taine and Jules Michelet.[277]

Sorensen says that "modern historians and historiographers owe a debt to [Carlyle] that few are prepared to acknowledge".[269] Among those few is C. V. Wedgwood, who said "It is the measure of Carlyle's greatness that, although he did make mistakes, he emerges none the less as one of the great masters."[278] Another is John Philipps Kenyon, who noted that despite his challenging style, Carlyle's "books are still read, and he has commanded the respect of historians as diverse as James Anthony Froude, G. M. Trevelyan and Hugh Trevor-Roper."[279]

Social and political movements

Never had political progressivism a foe it could more heartily respect.

Walt Whitman, "Carlyle from American Points of View"[280]

Chandler, writing in 1970, said that the influence of Carlyle's medievalism can be found "in much of the social legislation of the past hundred and more years".[251] It is perhaps most pronounced in Forster's Education Act,[281] the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act,[282] the Factory Acts, and the rise of such practices as business ethics and profit sharing throughout the 19th- and early 20th-centuries.[283] His attacks on laissez-faire became an important inspiration for U.S. progressives,[284] influencing the creations of the American Association for Labor Legislation, the National Child Labor Committee and the National Consumers League.[283] His economic statism influenced the progressive American Economic Association's early concept of "intelligent social engineering" (which has been described as elitist and eugenicist).[285] Leopold Caro credited Carlyle with influencing the social altruism of Henry Ford.[243]

Carlyle's influence on modern socialism has been described as "constitutive".[286] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels cited him in The Condition of the Working Class in England (1844–1845), The Holy Family (1845), and The Communist Manifesto (1848).[287] Alexander Herzen and Vasily Botkin valued his writings, the former calling him "a Scotch Proudhon."[288][289] He was one of the main "intellectual sources" for Christian socialism.[290] His importance to the British fin de siècle labour movement was acknowledged by major figures such as William Morris, Keir Hardie and Robert Blatchford.[291] Individual reformers took inspiration from him, including Octavia Hill,[292] Emmeline Pankhurst[293] and Jane Addams.[294]

Carlyle's aversion to the label notwithstanding, 19th-centuy conservatives were influenced by him. Morris Edmund Speare cites Carlyle as "one of the greatest influences" on Disraeli's life.[295] Robert Blake links the two as "romantic, conservative, organic thinkers who revolted against Benthamism and the legacy of eighteenth-century rationalism."[296] Leslie Stephen noted Carlyle's influence on his brother James Fitzjames Stephen in the early 1870s.[297]

Nationalist movements also looked to Carlyle. He was admired by the Young Irelanders, despite his opposition to their cause. Duffy wrote that in Carlyle, they found a "very welcome" teacher, who "confirmed their determination to think for themselves", and that his writings were "often a cordial to their hearts in doubt and difficulty".[298] Carlyle's philosophy was popular in the Antebellum South and eventual Confederacy.[299][300][301] In 1848, The Southern Quarterly Review declared: "The spirit of Thomas Carlyle is abroad in the land."[302] American historian William E. Dodd wrote that Carlyle's "doctrine of social subordination and class distinction . . . was all that Dew and Harper and Calhoun and Hammond desired. The greatest realist in England had weighed their system and found it just and humane."[303] Southern sociologist George Fitzhugh's notions of palingenesis, multi-racial slavery, and authoritarianism were profoundly influenced by Carlyle (as was his prose style).[304][305] Richard Wagner used Carlyle, whom he called a "great thinker", to justify his later German nationalism.[306] References to Carlyle appear in the writings of Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi throughout his life.[307]

More recently, figures associated with the Nouvelle Droite, the Neoreactionary movement, and the alt-right have claimed Carlyle as an influence on their approach to metapolitics.[308][309][310][311] At a meeting of the New Right in London in July 2008, English artist Jonathan Bowden delivered a lecture in which he said, "All of our great thinkers are shooting arrows into the future. And Carlyle is one of them."[312] In 2010, American blogger Curtis Yarvin labeled himself a Carlylean "the way a Marxist is a Marxist."[313] New Zealand-born writer Kerry Bolton wrote in 2020 that Carlyle's works "could be the ideological basis of a true British Right" and that they "remain as timeless foundations on which the Anglophone Right can return to its actual premises."[314]

Art

Carlyle's medievalist critique of industrial practice and political economy was an early utterance of what would become the spirit of both the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts movement, and several leading members recognised his importance.[315] John William Mackail, friend and official biographer of William Morris, wrote, that in the years of Morris and Edward Burne-Jones attendance at Oxford, Past and Present stood as "inspired and absolute truth."[316] Morris read a letter from Carlyle at the first public meeting of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.[317] Fiona MacCarthy, a recent biographer, affirmed that Morris was "deeply and lastingly" indebted to Carlyle.[318] William Holman Hunt considered Carlyle to be a mentor of his. He used Carlyle as one of the models for the head of Christ in The Light of the World and showed great concern for Carlyle's portrayal in Ford Madox Brown's painting Work (1865).[319] Carlyle helped Thomas Woolner to find work early in his career and throughout, and the sculptor would become "a kind of surrogate son" to the Carlyles, referring to Carlyle as "the dear old philosopher".[320] Phoebe Anna Traquair depicted Carlyle, one of her favourite writers, in murals painted for the Royal Hospital for Sick Children and St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh.[321] According to Marylu Hill, the Roycrofters were "very influenced by Carlyle's words about work and the necessity of work", with his name appearing frequently in their writings, which are held at Villanova University.[322]

apRoberts writes that Carlyle "did much to set the stage for the Aesthetic Movement" through both his German and original writings, noting that he even popularised (if not introduced) the term "Æesthetics" into the English language, leading her to declare him as "the apostle of aesthetics in England, 1825–27."[323] Carlyle's rhetorical style and his views on art also provided a foundation for aestheticism, particularly that of Walter Pater, Wilde, and W. B. Yeats.[324]

Reputation